Pleural effusion: recognition, triage and treatment

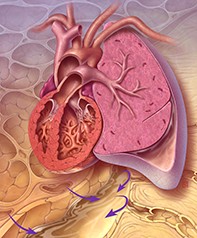

Pleural effusion has many possible causes, some of which are life-threatening and require urgent treatment, but is often not recognised because of its nonspecific presentation. Three cases illustrate the steps in recognising and triaging patients with pleural effusion.

- Pleural effusion can be a complication of a range of acute and chronic lung and extrapulmonary diseases, some of which are life-threatening and require urgent treatment.

- Patients with pleural effusion often present first to their GP with nonspecific respiratory symptoms.

- GPs should be vigilant and have a low threshold for excluding or confirming the diagnosis of pleural effusion, for example by ordering a chest x-ray.

- Triage of patients with pleural effusion for urgent, semi-urgent or elective referral is based on clinical parameters (e.g. presence of infective symptoms, recent trauma or bleeding risk, effusion size and suspicion of pulmonary embolism or malignancy).

- Patients with suspected empyema, haemothorax, pulmonary embolism-related pleural effusion or massive pleural effusion require urgent referral to a centre with pleural specialist support.

Pleural effusion is common and can be a complication of a wide range of lung and extrapulmonary diseases. Many patients with pleural effusion present first to their GP, but the diagnosis can be easily missed, partly because of the nonspecific presentation of most pleural effusions. If clinicians fail to recognise or suspect a pleural effusion then patients may be sent down an incorrect pathway for unnecessary investigations. More importantly, the diagnosis of any underlying (and often sinister) cause may be missed. Hence, the recognition of pleural effusions poses a significant challenge to GPs in their daily practice.

This article focuses on the clinical approach and elements to consider when assessing and triaging patients with nonspecific respiratory symptoms and also those with a known pleural effusion. The essential steps of assessment and triage are summarised in the Flowchart.

Assessment of patients with possible pleural effusion

History and clinical examination

Detailed clinical assessment, including good history taking and a thorough clinical examination, is usually the first step to diagnosing a pleural effusion. Some patients with pleural effusion have clearcut symptoms and a history suggesting a specific underlying disease. However, many patients have only nonspecific respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath and chest tightness. Although the lung has no pain fibres, the parietal pleura does. Therefore, the presence of chest pain, especially if pleuritic in nature, should prompt a high suspicion of pleural involvement in a range of conditions, especially pneumonia, pulmonary embolism and malignant pleural diseases.

Patients with respiratory symptoms require a thorough clinical examination. Reduced breath sounds and stony dullness on percussion of the lower part of the chest point are classic signs of a pleural effusion.

Chest x-ray

A simple chest x-ray is helpful when patients present with nonspecific respiratory symptoms, abnormal signs on respiratory examination and a suspicious history of unexplained constitutional symptoms. A chest x-ray is usually inexpensive and readily available, and can identify clinically relevant pleural effusions (Figure 1). Occasionally, a pleural effusion is an incidental finding on a chest x-ray investigating for nonrespiratory diseases.

Triage of patients with pleural effusion

If a pleural effusion is confirmed on chest x-ray then the next step is to establish the underlying aetiology. Over 60 conditions can lead to pleural effusion. The finding of a pleural effusion on chest x-ray should trigger clinicians to triage the patients based on clinical urgency. Some patients with a pleural effusion require urgent referral to a tertiary hospital for pleural drainage, whereas others can be investigated in an outpatient setting. Red flag features that require urgent referral are listed in Box 1.

Urgent referral

Patients with signs and symptoms suggesting any of the following conditions should be referred to the emergency department, preferably in a centre with pleural specialists, for immediate management.

Empyema: pleural effusion plus infective symptoms plus pleuritic pain

Parapneumonic effusions are pleural effusions that develop secondary to pneumonia. They include empyema, which refers to pleural effusions with pus or bacteria present in the pleural fluid. Parapneumonic effusions occur in up to 20 to 40% of patients with pneumonia and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

The clinical presentation of parapneumonic effusion or empyema depends on the timing of presentation, host response and the infective organisms. The combination of fever, infective symptoms, pleuritic chest pain and signs of pleural effusion should alert clinicians to the possibility of empyema (see the case scenario in Box 2 and Figures 2a and b). Patients with diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, excessive alcohol use, aspiration and poor oral hygiene are at increased risk of empyema. Significantly raised levels of inflammatory markers, such as white cell count and C-reactive protein level, are useful findings to support the differential diagnosis of pleural infection. Patients with these features, especially those with the above risk factors, should be referred for urgent pleural drainage whenever empyema is considered a possibility.

The presentation of pleural infection is highly variable, and a high index of suspicion should be maintained even in the absence of the above specific features. A recent study of over 4700 patients with community-acquired pneumonia found that 15% had a pleural effusion at initial presentation. Those with a pleural effusion had a 30-day mortality 2.6 times higher than those without an effusion. Thus, an urgent respiratory review is recommended in any patients with symptoms of a respiratory tract infection and a pleural effusion.

Patients with suspected empyema need urgent intercostal drainage plus appropriate broad-spectrum systemic antibiotic therapy to treat the infection. Intrapleural fibrinolytic plus deoxyribonuclease (DNAase) therapy is now the mainstay of treatment to facilitate drainage if the pleural fluid is loculated. Surgery may be required as a last resort.

Haemothorax: pleural effusion plus recent chest trauma, pleural procedure or bleeding risk

Haemothorax is defined as bleeding into the pleural cavity and is most often caused by trauma, including pleural procedures such as thoracentesis. Patients typically present with chest pain and tachycardia. Signs and symptoms of a pleural effusion ensue if bleeding is significant (see the case scenario in Box 3). Traumatic haemothorax can occur concurrently with pneumothorax, and both are emergency situations that require immediate referral to an emergency department for urgent management. Nontraumatic causes of haemothorax are less common but should be considered in patients with a bleeding diathesis, including the use of anticoagulants.

Pleural drainage with a large-bore catheter is usually needed to evacuate the blood clot and assess the rate of bleeding, together with close monitoring of haemodynamic status. Further localisation of the bleeding site by CT angiography of the chest is very valuable. Prompt assessment by interventional radiology (for intercostal artery embolisation) and/or thoracic surgery (for thoracoscopy or thoracotomy) teams are crucial when managing patients with haemothorax.

Pulmonary embolism-related pleural effusion: pleural effusion plus suspected pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism has a wide variety of presenting features, ranging from no symptoms to sudden death. The most common presenting symptom is dyspnoea, followed by chest pain (which is classically pleuritic but often dull) and cough. However, many patients, even some with massive emboli, have no symptoms or only nonspecific symptoms (see the case scenario in Box 4 and Figures 3a to c). It is therefore crucial to maintain a high level of suspicion for pulmonary embolism in the relevant clinical context, such as recent travel or use of oral contraceptive pills. Dyspnoea that is abrupt in onset or disproportionate to the size of the pleural effusion seen on chest x-ray, haemoptysis (usually mild), pleuritic chest pain, unilateral leg swelling, unexplained syncope or tachycardia should prompt clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism. Validated scoring systems such as the Wells score may help stratify the risk of pulmonary embolism and guide further investigation.

CT pulmonary angiography or ventilation-perfusion single photon emission CT (SPECT) can be used to detect pulmonary embolism. As many as half of all patients with pulmonary emboli have a pleural effusion on a CT scan. When the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is confirmed, systemic anticoagulation should be initiated. Pleural effusions associated with pulmonary emboli are generally small and will resolve with anticoagulation treatment.

Massive pleural effusion

Massive pleural effusion is often defined as opacification of two-thirds of hemithorax on chest x-ray. Patients with massive pleural effusion often have features of respiratory distress and mediastinal and tracheal shifting. They should be referred for assessment as soon as possible, especially if they are in respiratory distress.

Elective referral

Not all patients with pleural effusion require urgent pleural drainage. For example, patients in whom the pleural effusion is due to fluid overload caused by underlying cardiac, renal or liver disease can be managed with medical treatment.

Fluid overload due to cardiac, renal or liver disease

For patients with pleural effusion confirmed on chest x-ray and none of the aforementioned red flag signs, clinical assessment should include an evaluation of fluid status. Congestive heart failure is the most common cause of pleural effusion in primary care. Patients with hypoalbuminaemia from chronic renal or liver disease are also susceptible to fluid retention and pleural effusion. Further investigations, including renal and liver function tests, measurement of brain natriuretic peptide and echocardiography, may be considered.

A therapeutic trial of diuretics and optimisation of the medical management of the underlying disease, together with a follow-up chest x-ray to monitor response, are usually adequate for patients with fluid overload. However, if the clinical situation is atypical (e.g. asymmetrical effusion, fever, high levels of inflammatory markers or chest pain) or the pleural effusion does not show the expected improvement with diuresis then timely referral for pleural investigation is indicated.

Semi-urgent referral

For patients with a confirmed pleural effusion on chest x-ray who do not fall into the above urgent and elective referral categories, a semi-urgent referral for further management at a specialist centre should be considered. Semi-urgent referral is appropriate for patients with the following features.

Malignant pleural effusion: pleural effusion plus suspected malignancy

Pleural effusion is common among patients with malignancy. Most cancers can metastasise to the pleura and cause a malignant pleural effusion. Up to a third of patients with breast and lung cancers and 90% of those with malignant pleural mesothelioma develop a malignant pleural effusion.

A history of malignancy, smoking and exposure to asbestos (especially more than 20 years previously) can be relevant. Systematic evaluation for organ-specific symptoms is essential in assessing a patient with a new pleural effusion. Constitutional symptoms, including weight loss, sweating and poor appetite, should also raise the suspicion of malignancy. Patients should be examined for clubbing, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal organomegaly, breast lumps and skin lesions with a malignant appearance. Patients with pleural effusion together with clinical features of possible malignancy should be referred semi-urgently for further pleural investigation.

The presence of malignant cells in pleural fluid represents an advanced stage of cancer. After confirmation of the diagnosis, patients require fluid drainage for symptom relief and, if possible, pleurodesis to prevent fluid recurrence. Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) for long-term ambulatory drainage at home is increasingly used as it minimises the patient’s time in hospital and the need for repeat pleural procedures in the future. Most patients with an IPC learn how to drain the fluid with the help of a carer or community nurses. However, for patients who live in remote areas, GPs are often involved in overseeing IPC drainage.

Pleural effusion of uncertain cause: pleural effusion with no red flag signs or fluid overload features

Pleural effusion has many other pleural or systemic causes, including chylothorax (effusion from leakage of thoracic duct), rheumatoid arthritis, amyloidosis and drug-induced pleuritis (e.g. due to clozapine). Determining the cause of a pleural effusion is greatly facilitated by analysis of the pleural fluid, a pleural biopsy (image-guided, thoracoscopic or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery) and further imaging studies. A referral to a specialist pleural unit is warranted for patients in whom the cause of the pleural effusion is uncertain.

Conclusion

Pleural effusion is not a single disorder but a complication of a wide range of possible underlying diseases. Detailed clinical evaluation and a low threshold for ordering a chest x-ray can facilitate timely diagnosis and subsequent treatment of pleural effusion. Patients with a pleural effusion confirmed on chest x-ray should be triaged according to clinical urgency. Those with potentially life-threatening causes of pleural effusion or atypical presentations require urgent referral to an emergency department, preferably in a centre with pleural specialists, for immediate management. RMT