Advanced respiratory disease: managing symptoms in the last years of life

Symptoms in advanced respiratory disease are varied and commonly include breathlessness, fatigue and cough. Symptom control can be complex and difficult to navigate, particularly in the last few years of life as the disease progresses and patients’ needs escalate. Management is best optimised through holistic approaches, with management of individual symptoms alongside treatment of the underlying disease process.

- Symptoms in advanced respiratory disease are varied, complex and require specific attention to improve patient experiences.

- Key symptoms include the triad or respiratory cluster of chronic breathlessness, fatigue and cough, as well as depression and anxiety, insomnia, cachexia, pain and dry mouth.

- Management is best optimised through a holistic approach, with individual symptoms also addressed if they persist despite maximising management of underlying disease.

- Nonpharmacological interventions for breathlessness, such as mobility aids, activity pacing and breathing training have been shown to have good effect.

- Low dose opioids may be prescribed for some people with severe chronic breathlessness with the intention of reducing breathlessness to an acceptable level, as complete symptom amelioration is often not possible.

- The psychological impact of advanced respiratory disease is often overlooked and needs to be directly addressed in best practice care.

- Early introduction of advance care planning (ACP) offers patients the opportunity to document their care preferences and address evident lack of support for chronic lung disease in the final stages of disease. The conversation around ACP should be ongoing as patients’ preferences evolve throughout disease progression.

Management of advanced respiratory disease has increasingly shifted to primary care and community settings owing to a growing focus on supported, home-based care and preferences to avoid hospital presentation. Symptoms in advanced respiratory disease are varied, and can be complex and difficult to manage, particularly in the last years of life as the disease progresses and patients’ needs escalate.1 The symptoms discussed here are most common in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but are also relevant to other chronic conditions such as pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis and lung cancer. Breathlessness in particular is highly prevalent in advanced cancers and heart failure.2

Defining the last years of life in advanced respiratory disease

Despite well-recognised fluctuation in chronic respiratory conditions (often with periods of exacerbation), indicative prognostic characteristics have been established. In particular, the question ‘Would I be surprised if this patient did not survive the next 12 months?’ is a useful clinical prompt.3 This question has been found to have high specificity compared with gold standards framework prognostic indicators and is a simple prompt for clinicians to actively focus on symptom control, in combination with ongoing disease-directed management of the underlying condition.3

The nature and intensity of symptoms also signal patients’ changing needs. A modified Medical Research Council breathlessness scale (mMRC) score of 3 (‘I stop for breath after walking about 100 meters or after a few minutes on level ground’) or 4 (‘I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing or undressing’) are indicative of advanced disease in the last years of life.4

Hospitalisation with an acute exacerbation of COPD has long been recognised as a prognostic indicator of advanced respiratory disease.5 Mortality risk varies across studies; however, a recent retrospective study reported one- and five-year mortality of patients hospitalised for COPD as 26.2% and 64.3%, respectively, with mechanical ventilation further increasing these risks.5 Acute hospitalisation is therefore recommended as an opportunity to discuss and plan for future care.5,6 Low body mass index below 21.75 kg/m2 and cachexia are also reliable prognostic indicators in advanced respiratory disease.7,8

Although the ability of prognostic indicators to predict death varies considerably across patients, its utility lies in the opportunity to prompt an additional care focus – notably the treatment of symptoms as a specific treatment goal.

Management of key symptoms

Symptoms in advanced respiratory disease vary; however, key symptoms relate to a triad, or ‘respiratory cluster’, that includes chronic breathlessness, fatigue and cough. Other important symptoms include depression, anxiety, insomnia, cachexia, pain and dry mouth.1 Although a broad and holistic approach to symptom management is recommended, individual symptoms should be addressed if they persist despite optimal management of underlying disease.1 A useful summary of evidence-based approaches to individual symptom management of COPD is presented in Box 1.1

Breathlessness

Chronic breathlessness is highly distressing for patients with chronic respiratory disease, and both GPs and specialists commonly voice a lack of confidence in its management. Breathlessness is multidimensional and is defined as ‘an unpleasant subjective experience of discomfort with breathing that worsens as underlying disease processes increase in severity; in its chronic and severe state, it can lead to significant disability, progressive inactivity, social isolation and substantive suffering’.9 In addition, ‘chronic breathlessness syndrome’ is breathlessness that ‘persists despite optimal treatment of the underlying pathophysiology and that results in disability’.10 A stepped approach to the evaluation and treatment of breathlessness is helpful and includes:

1) addressing reversible contributing causes, including anaemia, pleural effusion or anxiety; and engaging

2) nonpharmacological; and

3) pharmacological interventions.10

Nonpharmacological interventions

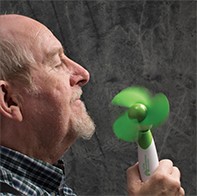

Nonpharmacological interventions for breathlessness are accessible and beneficial.1 For example, activity pacing, mobility aids and adjusting the living environment can assist in conserving energy for valued activities.1 Personalised exercise programs and increased physical activity can improve stamina, and yoga and Tai Chi have been shown to be safe and to improve breathlessness for some people with advanced lung disease.11 Hand-held motorised fans (Figure and videos) are similarly low harm, low cost, easy interventions that directly target the sensation of breathlessness.1 Breathing retraining, accessed through specialist physiotherapy services, can also help improve associated dysfunctional breathing patterns.1

Anxiety associated with breathlessness can lead to avoidance of those physical activities that address deconditioning.1 Psychological and counselling therapies, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), discussed below, can address negative thought processes and reluctance to engage in helpful activities.1,12 Similarly, education and supported self-management can help patients improve self-efficacy, which in turn can reduce anxiety and depression, increase activity and social contact and boost quality of life.1

Opioids

Opioids are the primary pharmacological approach to managing breathlessness.2 Evidence suggests that low-dose opioids (30 mg/day) are safe, albeit with side effects; however, efficacy is variable.13,14 Educating prescribers and patients on the use of opioids as an aid to dampen breathlessness to an acceptable level, rather than remove the symptom altogether, is important; this distinction is significant in facilitating acceptability and confidence for both patients experiencing breathlessness and clinicians prescribing these agents.15,16

Prescribing opioids concurrently for unrelated conditions increases the risk of cumulative dosing and compounding of side effects and safety issues, such as the impact on driving. Safety issues, in particular, should be clearly explained and discussed with the patient (Box 2).15,16 If starting a patient on opioids to manage breathlessness, either short-acting or long-acting agents should be prescribed, but not both, and commitment to ongoing review to monitor response and potential adverse effects is required.

The Table outlines two approaches to prescribing morphine for patients with refractory breathlessness. Regimen 1 provides guidance using an immediate-release opioid, that is commenced at a lower dose and allows for greater control and adjustment by the patient or carer as needed. A disadvantage of a lower, potentially subtherapeutic dose, however, may be suboptimal relief with consequent poor compliance and premature discontinuation of the treatment by the patient. Regimen 2 summarises an evidence-based approach with a sustainedrelease opioid; this regimen allows for initiation at a higher dose, thereby improving the potential for therapeutic benefit and subsequent patient compliance; however, patients and carers may be reluctant to use sustained-release opioids at this higher dose and for longer term treatment.

Benzodiazepines are not recommended to treat breathlessness, except as second- or third-line therapy or at the very end of life.15 Mirtazapine has shown promise in severe breathlessness, and further clinical investigation, including safety in feasibility studies, is underway in Europe and Australia.17 Further efficacy trials for anxiolytics are needed; however, in the interim, all patients receiving such agents should be monitored for benefit and adverse effects when treated with these or other symptom measures.2,15

Fatigue

Fatigue is defined as ‘a profound feeling of physical and psychological weariness that is not relieved by sleep or rest’.1 Similar to breathlessness, fatigue is complex and requires a multicomponent approach to management, including physical conditioning (individualised pulmonary and exercise programs); psychological support; supported self-management; and resilience training. Additionally, treatment for comorbid depression is crucial, as this may compound the experience of fatigue.1

Occupational therapy-driven management, with a focus on daily life adjustment and maximising participation, has shown promise. Such evidence-based interventions aim to increase patients’ understanding of fatigue; identify exacerbating factors; and facilitate development of fatigue management strategies (Box 3).18

Cough

Chronic cough related to underlying maximally treated respiratory disease is a significant source of distress for patients.1 Primary management approaches include physiotherapy, speech and language therapies (such as sputum-clearance techniques, cough control and cough-reflex hypersensitivity training) and psychoeducational counselling (Box 1).1

Pharmacological treatments are not well evidenced; however, the neuromodulator gabapentin has been used to treat refractory dry cough, and the antitussive P2X3 antagonists, which target airway vagal afferent nerve hypersensitisation, may provide a pathway to mediate cough reflex. Although P2X3 antagonists are not yet available in Australia, preclinical and preliminary trial data are promising and P2X3 antagonists may be the new dawn in addressing this distressing symptom.19

Psychological impact

One often overlooked area within advanced respiratory disease is the psychological impact on patients, particularly in light of sustained symptoms.20,21 The relationship between chronic respiratory disease and depression and anxiety is well documented, as is social and existential isolation; psychological issues are reported in as many as 60% of people with COPD.12,22,23

Despite disease and symptom management optimisation, for many, a significant burden remains. Raising issues around psychological coping and patient experience provides patients the opportunity and permission to voice the full impact of their condition.

Key treatments for depression and anxiety include behavioural therapies and CBT, as well as pharmacological interventions (Box 1). Multicomponent exercise training has also shown positive impact for patients with advanced respiratory disease and depression.1 Psychological therapy and counselling (‘talking’ therapies’) are acknowledged as useful, particularly in patients with chronic disease. CBT is a well established treatment for anxiety and depression that seeks to increase a patient’s understanding of their current difficulties and help manage unhelpful thoughts, and has shown promising outcomes for patients with COPD.12 Of importance, several studies, including a recent large randomised controlled trial, showed that respiratory nurses trained in, and delivering CBT, improved anxiety and healthcare utilisation (emergency department presentations and hospitalisation) among patients with chronic respiratory disease.20,24 Peer and facilitated support groups have similarly shown improvement in the wellbeing of patients with chronic respiratory conditions.20 Empowerment through shared experience and collegial support may also improve active engagement with healthcare.20

Connecting patients with support and social services is increasingly important.25 ‘Social prescribing’, in which primary care services actively link patients to support services within the community and volunteer sectors can help improve health and wellbeing.26 Social prescribing activities, including community gardening, group learning, volunteer work and music- and arts-based activities, are of particular value to patients with chronic conditions, such as advanced respiratory disease, in whom disease-related social isolation plays a key role in psychological dysfunction.

Other symptoms

Other symptoms associated with chronic respiratory disease include anorexia, dry mouth and insomnia. Evidence for the management of these symptoms is varied. Anorexia management relies primarily on nutritional supplementation, patient education and dietetic support. For patients with dry mouth, it can be helpful to review inhaler therapies that may contribute to this symptom, and consider changing the device or the medication. Additionally, local topical therapies (such as oral lubricants of saliva substitutes) can be helpful.27 Insomnia and daytime sleepiness is treated with sleep hygiene and CBT, and benzodiazepines may be prescribed for short-term intervention.1 Comorbidities may also contribute to symptoms, thus the approach to management should always be to maximise the treatment of all contributing underlying conditions.

The importance of advance care planning

Despite the life-limiting nature of chronic respiratory diseases, few patients have plans in place for the later stages of disease and care, and fewer than 18% of patients with COPD in Australia access palliative care in the last 12 months of life.28-31

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process and opportunity in which patients ‘think about, discuss and record preferences for the type of care they wish to receive and the outcomes they would consider acceptable’.32 The process involves a series of conversations engaging patients and their family in exploring values, burdens and preferences, and allows healthcare professionals, the patient and their family to develop a shared understanding of how to best provide care that addresses and reflects the person’s expressed goals.32

ACP increases palliative care involvement and reduces the likelihood of clinically futile treatments and decision-making in a period of crisis. For patients with COPD, ACP can provide a heightened sense of control and reduce anxiety and depression.33,34

Providing multiple and early opportunities to discuss long-term care wishes and priorities with patients is recommended.32 These conversations are likely to evolve as the patient’s perspectives may change over time, emphasising the importance of ongoing conversations and willingness for continued discussion of healthcare preferences, even after an advance directive is in place.32 Advance Care Planning Australia provides information on ACP, and includes questions to help start the conversation (Box 4) and videos for health professionals.32

Efficient conversations for long-term care

Patient-driven and patient-led consultations are sometimes erroneously considered too time consuming within the constraints of busy clinical practice.35 Instead, evidence indicates that interactions commenced with a simple question as to the patient’s priorities result in more time-efficient consultations and care that is more strongly aligned with patient’s current and ongoing needs.36 This becomes increasingly important when addressing care within the final years of life. Creating opportunities for patients to voice their priorities for care and ensuring the opportunity is taken to start a longer discussion over several consultations that plans care for now and the future, rather than attempting to address all issues raised, is essential.35,36

Conclusion

Management of respiratory symptoms is best optimised through holistic approaches that address individual symptoms in addition to the underlying disease. Symptom burden commonly escalates in the last years of life as the disease progresses. Identifying patients within this category is crucial for well-managed and planned care. Key prognostic indicators for chronic disease include the question ‘Would I be surprised if this patient did not survive the next 12 months?’. Similarly, discussing patients’ priorities for care and early engagement with ACP can better facilitate care that addresses their ongoing needs. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.