The first COPD Clinical Care Standard: use of spirometry for accurate and early diagnosis

The underuse of spirometry for the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a longstanding challenge for healthcare systems worldwide. The COPD Clinical Care Standard has identified the use of spirometry as one of 10 priority areas for action for clinicians and health services. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care is leading a number of initiatives to enhance access to spirometry and to use spirometry to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of COPD in the community.

- The first national quality standard for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard, was published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care in October 2024.

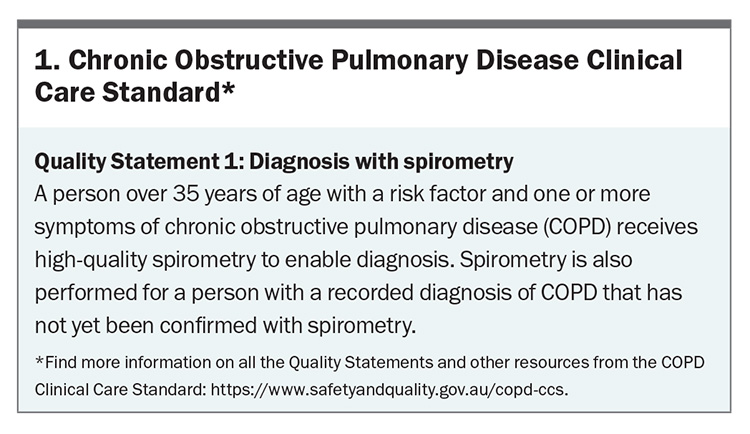

- The Standard identified the use of spirometry as essential for the accurate and early diagnosis of COPD, as one of 10 priority areas for action for clinicians and health services.

- Spirometry is underused in general practice, likely leading to both misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of COPD.

- The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care is leading a number of initiatives to enhance access to and use of spirometry for the accurate diagnosis of COPD in general practice.

COPD is a leading cause of ill health and death across the world.1 In Australia, it is the fifth-leading cause of overall disease burden and accounts for 50% of the disease burden from respiratory conditions.2 Although COPD is a preventable and treatable condition, it was recorded as an underlying cause of 10% of all deaths and 35% of all respiratory deaths in Australia in 2022.2 These grim statistics, together with the fact that COPD is one of the leading causes of potentially preventable hospitalisations, indicate there is much that can be done to improve health outcomes for people with COPD.3

Recognising the substantial and growing health burden from COPD in the Australian community, and the urgent need to improve the quality of care for people with COPD, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (‘the Commission’) published the first national quality standard for COPD, the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard (‘the Standard’), in October 2024.1,4-6 The Standard addresses 10 priority areas of care, presented as Quality Statements, where improvements in clinical practice are expected to translate to better health outcomes (https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/copd-ccs). This article focuses on Quality Statement 1: Diagnosis with Spirometry (Box 1) and discusses the use of spirometry as a priority area for quality improvement.

Underuse of spirometry in general practice

A diagnosis of COPD should be considered in any person over the age of 35 years old who has regular symptoms, such as dyspnoea, cough, sputum production, a history of recurrent lower respiratory tract infections or a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease. Importantly, spirometry showing the presence of a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 0.7 is required to establish a definitive diagnosis of COPD.7 However, there are a number of practical challenges that have hindered the routine use of spirometry in general practice, leading to either an incorrect COPD diagnosis for a person who does not have the condition (misdiagnosis or overdiagnosis) or a missed COPD diagnosis for a person who does have the condition (underdiagnosis).4,8,9

A robust analysis of primary care practice data in the UK provided a sobering picture of the problem. In 2019, 41% of patients who had a new diagnosis of COPD and who were considered to be at high risk (i.e. had a history of at least two moderate or at least one severe exacerbation(s) in the previous 12 months) had no record of undergoing spirometry in the 12 months prior to diagnosis. The absence of diagnostic confirmation with spirometry was also associated with additional gaps in care: most of these patients had not had a review of their exacerbation history (58%) or evaluation with a COPD Assessment Test (75%) or cardiac risk assessment (81%) in the 12 months before or after diagnosis. Many of these patients had also not been offered nor received a referral for pulmonary rehabilitation when indicated (66%) nor received a medication review within six months of treatment initiation or change (45%).10

In Australia, the extent to which spirometry is currently used for the diagnosis of COPD in general practice is not known. However, the findings of one study conducted across 41 general practices in Melbourne in 2015–17 provides evidence of underuse, along with misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of COPD.11 One-third (37%) of participants with a prior ‘diagnosis’ of COPD did not meet the spirometric definition of COPD, indicating misdiagnosis. On the other hand, 17.6% of participants who were identified as being at risk of COPD but with no prior diagnosis of COPD were confirmed to have COPD following spirometric testing, indicating underdiagnosis of the condition in at least one in six of people.11

Barriers to spirometry in general practice

The underuse of spirometry for the diagnosis of COPD is a longstanding challenge for healthcare systems worldwide.8 In Australia, there are a number of barriers that may potentially explain the underuse of spirometry in general practice.9 Clinician-related barriers include a perceived lack of clinical utility of spirometry and low confidence in performing and interpreting spirometry. Practice-related barriers include cost, time pressure and the difficulties involved in having spirometers on site, including their maintenance and calibration, and accessing accredited spirometry training for staff. People with COPD may find spirometry a difficult procedure, as it requires maximal respiratory effort; thus, patient reluctance to attend an appointment for spirometry testing is also a contributing factor.9

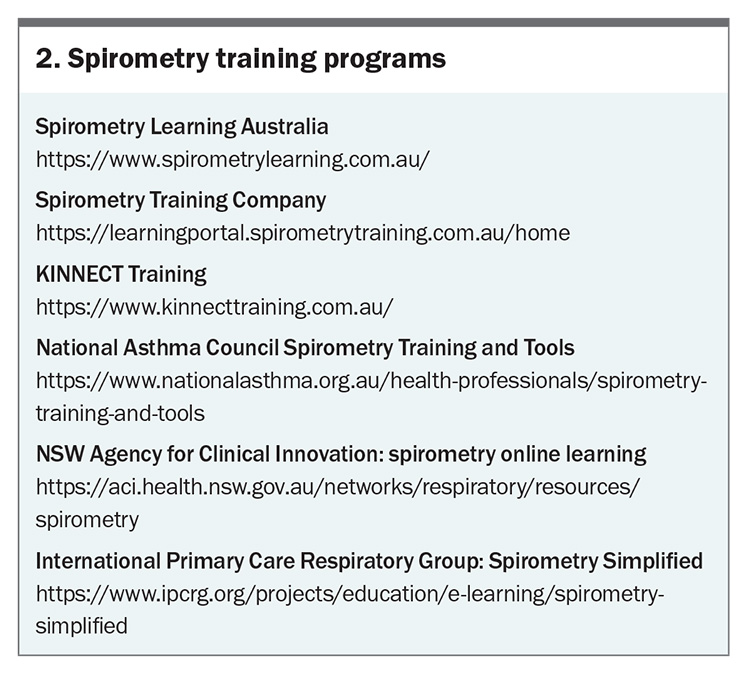

There are a number of training programs that GPs and practice nurses can access to gain proficiency in spirometry (Box 2). Alternatively, GPs who cannot provide spirometry could ensure they know where to refer patients locally for the test. HealthPathways may have a list of locally available private and public hospital-based respiratory laboratories and Asthma Australia provides a list of national respiratory labs (https://asthma.org.au/respiratorylabs/). Local Primary Health Networks (PHNs) might also be able to help establish a local spirometry pathway when a gap in services exists. However, it is important to recognise that addressing existing barriers may well go beyond education and training, and will likely involve policy and system changes, in addition to cultural and practice change at the clinician level.9

Notably, the use of spirometry for COPD diagnosis was substantially reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, most likely because of the additional requirements for infection control and the associated costs.4,12,13 The Commission has updated guidance, the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare, to support improved spirometry access while maintaining appropriate infection control measures.14 As evidence continues to evolve, the Commission and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand also continue to work collaboratively to ensure guidance balances both safety and diagnostic accessibility.

Co-ordinating a national effort to drive priority quality improvement in COPD care

In developing the first national quality standard for COPD, the Commission has articulated 10 quality statements that should underpin the care of a person who is at risk of developing COPD or who has a confirmed diagnosis of COPD.5 Each quality statement is accompanied by one or more quality indicators (measures) that may be used to assess and monitor specific aspects of care at the local level. For example, to determine the extent to which spirometry is used for the diagnosis of COPD, general practices can determine the proportion of patients with a recorded diagnosis of COPD for whom the healthcare record documents their spirometry results. Tracking these data over time will help practices to identify gaps in and barriers to optimal care, and work towards implementing strategies to address these gaps.5

Furthermore, to support the implementation of the Standard and inform strategies to improve service provision, the Commission is leading a number of initiatives that will provide contemporary data on the use of spirometry at both national and local practice levels. First, at a national level, as part of the Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation Series, the Commission will report on the number of Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)-subsidised spirometry services per 100,000 people, aged 35 years and older, between 2015–16 and 2022–23.15 These data will be disaggregated to inform how the use of spirometry services varies by geographical location and Primary Health Network, and how the services might be impacted by remoteness and socioeconomic status. These data will establish if there is significant variation in the provision of spirometry services across regions and certain population groups and will inform state and territory health jurisdictions and Primary Health Networks where to facilitate increased access to spirometry service provision.

Second, from 1 January 2023, the Commission became the custodian of the MedicineInsight Program, a quality improvement program developed by NPS MedicineWise in 2013 as a pilot and established in 2017 with funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.16 The MedicineInsight Program collects deidentified patient-level data from participating general practices to support quality improvement. By feeding back these data, the program allows individual GPs to reflect and compare their clinical activities with other GPs in their practice, as well as local, regional and national benchmarks, and evidence-based guidelines.

In December 2024, the Commission conducted a preliminary analysis of MedicineInsight data to determine the extent to which spirometry is used in the management of COPD in general practice. Of the 39,000 people with a recorded diagnosis of COPD, only two in five had a record of spirometry testing.17 Although this finding is unsurprising given the known barriers to spirometry testing, this represents an opportunity to improve COPD care. In 2025, the Commission is anticipated to release a MedicineInsight COPD report to enable quality improvement activities. This report will give enrolled GP practices and practitioners an easy way to review their own spirometry data, compare them to their peers, undertake quality improvement activities and review the impact on their spirometry data. GPs who are interested in participating in the MedicineInsight Program can sign up online (https://www.safety andquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators-measurement-and-reporting/medicineinsight).

Conclusion

In developing the first national quality standard for COPD, the Commission has established a set of nationally consistent criteria that can be used by individual clinicians and health services to assess and monitor the quality of care they provide for people with COPD. Enhanced access to and use of spirometry to confirm the diagnosis of COPD is a key area for quality improvement. The Commission is committed to reporting on the current provision of spirometry services at practitioner, practice and system levels, which will inform and guide policy and encourage practice change. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Sukkar is a member of the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) Research Sub-Committee. Professor Emeritus Alison has received a Medical Research Future Fund grant (payment made to The University of Sydney); has received payment from Boehringer Ingelheim for a talk and from the Australian Physiotherapy Association for updating a course; has participated in a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the Targeting treatable traits in COPD to prevent hospitalization trial through Monash University; is chair of the Australian Pulmonary Rehabilitation Network and a member of the COPD Advisory Committee at Lung Foundation Australia. Dr Bhasale, Dr Fong and Dr Sukkar are employed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), which is the organisation responsible for developing the COPD Clinical Care Standard. Dr Fong is an Expert Group Member at Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, North Melbourne, Vic; Treasurer at Hunter GP Association, Newcastle; and President at GP Deputising Association. Dr Hancock is Chair of the Primary Care Clinical Council at Lung Foundation Australia and Chair of the RACGP Respiratory Medicine Specific Interests Network; has received consulting fees from ACSQHC as a member of the advisory group for the development of the COPD Clinical Care Standard; has received payment for attendance at Advisory Boards and for presentations from Chiesi, GSK and HealthEd, and payment for spirometry training of health professionals from Spirometry Learning Australia; and has received support for travel to a working meeting from Astra Zeneca and conference registration support from Chiesi. Professor Smallwood is President of the TSANZ; and NHMRC Emerging Leader Fellow. Ms Roberts is the NSW State Executive of the TSANZ; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Boehringer Ingelheim; and has received payment for presentations from Lung Foundation Australia, Boehringer Ingelheim, the Australian College of Nursing and Astra Zeneca.

References

1. Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022; 378: e069679.

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd (accessed March 2025).

3. AIHW. Potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia by small geographic areas, 2020–21 to 2021–22. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/potentially-preventable-hospitalisations-2020-22/data (accessed March 2025)

4. Lung Foundation Australia. Transforming the agenda for COPD: a path towards prevention and lifelong lung health - Lung Foundation Australia’s blueprint for action on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 2022 - 2025. Milton, Queensland: Lung Foundation Australia. Available online at https://lungfoundation.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/LFA_COPD-Blueprint_Print-V2.pdf (accessed March 2025).

5. Australian Commission on Safety. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety; 2024. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-clinical-care-standard (accessed March 2025).

6. Fong L, Sukkar MB, Ahmed R, Bhasale A. Establishing a national standard to achieve better outcomes for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aust Prescr 2024; 47: 168-170.

7. Dabscheck E, George J, Hermann K, et al. COPD-X Australian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2022 update. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 415-423.

8. Perret J, Yip SWS, Idrose NS, et al. Undiagnosed and ‘overdiagnosed’ COPD using postbronchodilator spirometry in primary healthcare settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2023; 10: e001478.

9. Lim R, Smith T, Usherwood T. Barriers to spirometry in Australian general practice: a systematic review. AJGP 2023; 52: 585-593.

10. Halpin DMG, Dickens AP, Skinner D, et al. Identification of key opportunities for optimising the management of high-risk COPD patients in the UK using the CONQUEST quality standards: an observational longitudinal study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023; 29: 100619.

11. Liang J, Abramson MJ, Zwar NA, et al. Diagnosing COPD and supporting smoking cessation in general practice: evidence-practice gaps. Med J Aust 2018; 208: 29-34.

12. Borg BM, Osadnik C, Adam K, et al. Pulmonary function testing during SARS-CoV-2: an ANZSRS/TSANZ position statement. Respirology 2022; 27: 688-719.

13. Hancock K, Parsons R, Schembri D. Conducting spirometry in general practice. Infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respiratory Medicine Today 2020; 5(2): 28-33.

14. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-guidelines-prevention-and-control-infection-healthcare (accessed March 2025).

15. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation Series. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2021. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/healthcare-variation/australian-atlas-healthcare-variation-series (accessed March 2025).

16. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. MedicineInsight. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2023.Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators-measurement-and-reporting/medicineinsight (accessed March 2025).

17. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. MedicineInsight GP Snapshot: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators-measurement-and-reporting/medicineinsight#new-resource-medicineinsight-gp-snapshot-copd (accessed March 2025).