Parasomnias and insomnia in childhood: assessment and management

Sleep is a key building block for childhood development as it is essential for learning, wellbeing and school performance. Common disruptive but nonrespiratory sleep issues in children include parasomnias and insomnia. Effective sleep management strategies are available to improve outcomes in children and their families.

- Insomnia can include difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep or early morning awakening.

- Insomnia is often accompanied by mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, that should be addressed within treatment planning and management.

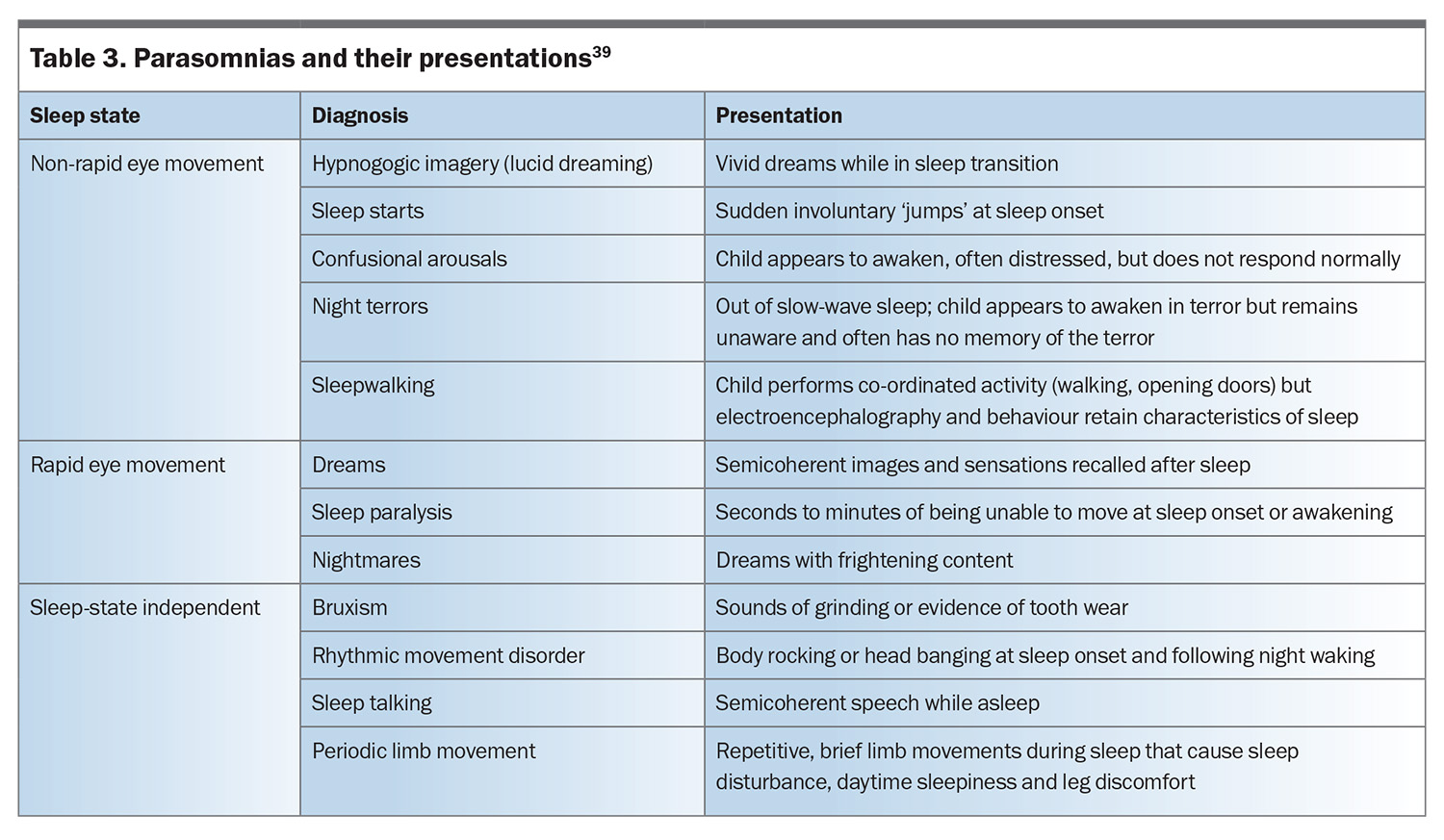

- Parasomnias can present as involuntary movements, such as sleepwalking or periodic limb movement, or experiential episodes, such as lucid dreaming or night terrors. These episodes are usually brief but can last up to an hour.

- The BEARS screening tool is a helpful mnemonic to aid sleep history-taking for major sleep disorders in children aged 2 to 18 years. Parental questionnaires can assist in further clarification in the identification and diagnosis of sleep disorders.

- Behavioural and other nonpharmaceutical strategies should be the first-line treatment for the management of both insomnias and parasomnias. If not resolved, pharmaceutical strategies can be used in conjunction with behavioural treatments.

- Practitioners should refer the child to a paediatric sleep specialist if the presentation is ambiguous or other medical or respiratory issues are suspected. A sleep specialist, psychiatrist or paediatrician should be consulted if medication is being recommended.

Sleep is vital for physical and mental health and can influence many aspects of childhood development, including memory, learning, executive functioning and adaptive behaviour(s).1 An estimated 30% of parents of children aged 1 to 5 years report that their child has problematic sleep.2,3 Inadequate sleep duration and sleep quality are important to explore when a child presents with developmental concerns in primary care. Infant sleep requires separate consideration and is not the focus of this article.

Poor sleep in a child can also disturb sleep and daytime functioning among caregivers and siblings.4 The timing of sleep and behaviours around settling to sleep are modifiable. Treatment options are therefore important to consider, as they can improve outcomes for the child and their family.

When identifying sleep issues, taking a detailed history with a primary caregiver is important to define the primary problem and ascertain its impact on the child and their family. This information can guide the treatment approach, informing whether behavioural sleep modifications can be effective or whether further investigation or specialist referrals are required.

This article discusses common sleep disorders experienced by children, including difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep (DIMS), sleepwalking (somnambulism), night terrors, sleep talking and sleep paralysis. These conditions are commonly grouped together and referred to as insomnia and parasomnia disorders.5,6 This article provides a framework to help clinicians evaluate, investigate and manage these sleep disorders in practice.

Insomnia

Insomnia can be defined as a complaint of sleep quantity or quality and can include difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and/or early morning waking.6 The main complaint is inadequate sleep and resulting symptoms of sleep deprivation. To diagnose insomnia, sleep difficulties must occur at least three nights per week and be present for at least three months. Insomnia presentations may differ depending on age.

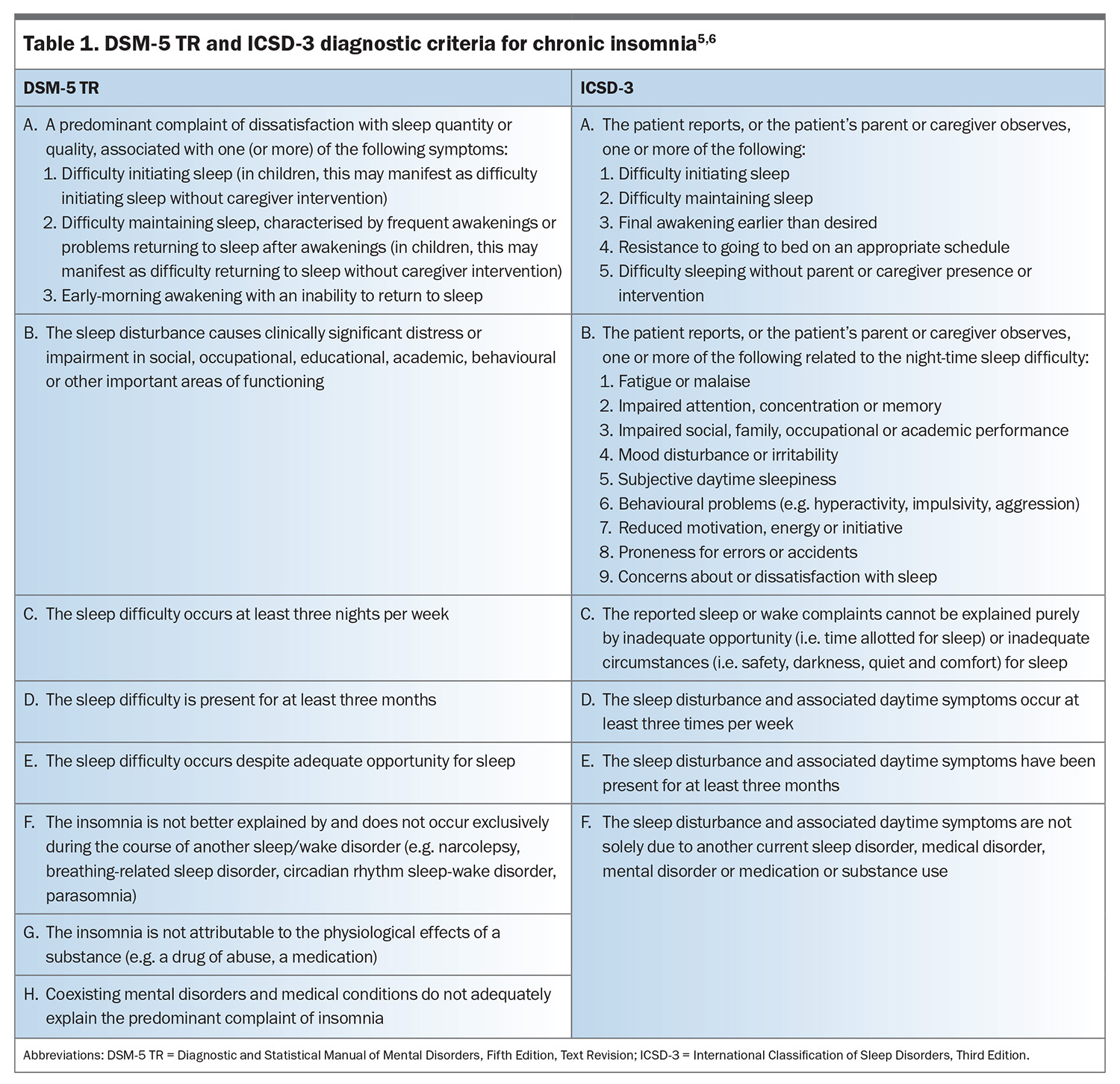

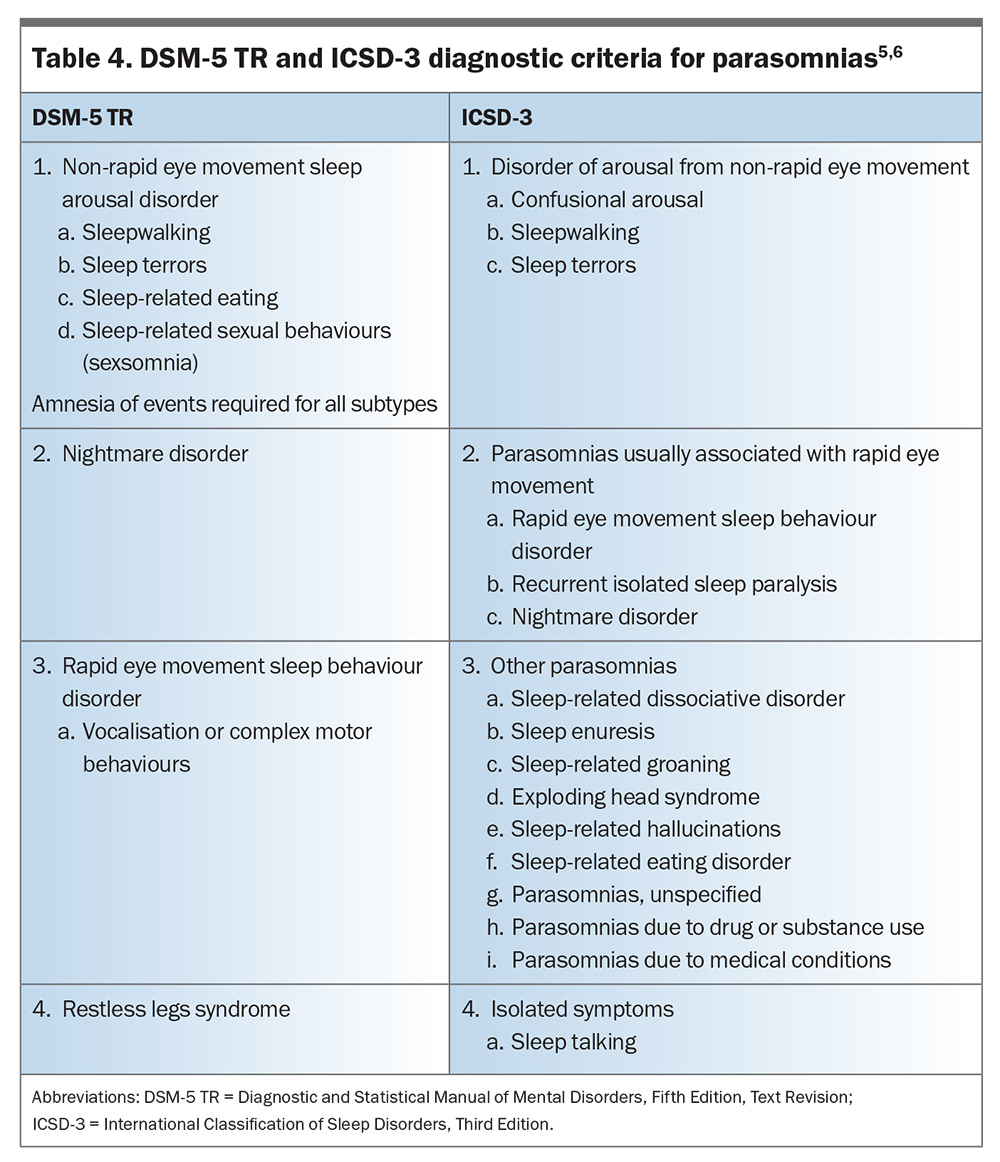

Insomnia can be broken down into multiple sub-diagnoses, which can help direct management. The criteria for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5 TR), and International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), classifications of insomnia are outlined in Table 1.5,6

Insomnia can cause significant distress around sleep times or impairment in daytime functioning. Toddlers and preschool-aged children may present with bedtime stalling or resistance, frequent night waking or sleep-onset associations such as thumb sucking or rocking.7 For school-aged children, the daytime symptoms may appear as increasing difficulty at school, irritability, attention or concentration impairment and issues within social settings.5 In adolescents, insomnia may present as poor sleep quality (nonrestorative), poor sleep maintenance, anxiety around falling asleep, excessive napping and sleep phase delay.8

In younger children, the most common type of insomnia is behavioural insomnia of childhood (BIC). The ICSD-3 subclassifies BIC into three types:

- sleep-onset association type

- limit-setting type

- mixed type.

The sleep-onset association type is explained by a child’s dependency on specific stimulation, objects or settings for sleep initiation or returning to sleep after waking.9 The most common example is when a child requires a pacifier or the presence of a parent to fall asleep. The BIC limit-setting type is characterised by bedtime resistance, which usually results from limit-setting difficulties by caregivers.10 This may present as a refusal to go to bed or demands at bedtime, resulting in delays to sleep onset. The BIC mixed type involves the presence of both insomnia types. By comparison, the DSM-5 TR categorises insomnia into initial insomnia (difficulties with sleep onset), middle insomnia (difficulties with sleep maintenance) and late insomnia (early-morning waking). The DSM-5 TR further specifies whether the symptoms are episodic, persistent or recurrent.

Sleep anxiety can present as excessive worrying during sleep onset, with these worries appearing differently through childhood. This is classified as psychophysiological insomnia, another subtype of insomnia, classified within the ICSD-3. It is characterised by heightened arousal and learned sleep-preventing behaviours. Children may experience anxiety and worries around bedtime and falling asleep and may have difficulty sleeping in their own rooms. Preschool- and school-aged children may have fears around night-time and their environment. Some examples include fears of the dark, of monsters, of break-ins or from their imagination (e.g. scary stories, or events that may have appeared in movies or television shows). For some children and adolescents, sleep anxiety can present within the family or the school setting. For example, excessive worries about their day (social events including school, friendships or possible conflicts), upcoming events (exams, sporting or other performance-based events) or break-ins at their home.

Insomnia is often accompanied by mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, that should be addressed within treatment planning and management.6 Persistent sleep disturbances are risk factors for further mental illness and are linked to depression, anxiety, substance abuse and other mental health conditions.11 They can also represent early signs of mental illness episodes with early intervention allowing for the possibility to pre-empt or reduce the occurrence.6 Sleep and mental health issues are bidirectional; anxiety and depression symptoms are heightened by a lack of sleep, and these symptoms in turn lead to difficulty falling asleep.12,13 This is especially prominent among adolescents, and screening for comorbid mental health diagnosis and comanagement are needed.

Assessment and diagnosis

All types of insomnia are best identified through detailed history-taking in the initial consultation and parental observations and interviews.14 The BEARS screening tool is a helpful mnemonic to aid sleep history-taking for major sleep disorders in children aged 2 to 18 years:15

- B: bedtime problems

- E: excessive daytime sleepiness

- A: awakenings during the night

- R: regularity and duration of sleep

- S: snoring.

The use of sleep diaries to record sleep patterns before consultations can help to quantify sleep-related complaints and assist in identifying specific issues. Sleep diaries are also useful in determining if sleep difficulties are related to specific routine behaviours, such as inappropriate or inconsistent napping or sleep schedules. Validated sleep screening questionnaires are useful to gain further clarity of specific issues.

Questionnaires such as the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) and Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) may be useful to assess for sleep disorders in children of different ages (e.g. school aged, adolescents).16,17 It is important to rule out medical and respiratory issues such as restless leg syndrome or obstructive sleep apnoea as the cause for insomnia.14 Resources with further information on this topic are available through the Australasian Sleep Association.18 The use of objective sleep assessment tools, such as actigraphy, in addition to sleep history-taking and parental observations, can assist with diagnosis.19 Actigraphs are small movement detectors (accelerometers) generally placed on the wrist that can distinguish sleep from wake using algorithms to quantify the reduced movement associated with sleep. They have been shown to be a reliable method for determining sleep in children when compared against polysomnography (PSG).20 Referral to a paediatric sleep specialist for PSG may be required if the presentation is ambiguous or other medical or respiratory issues are suspected.21

Sleep management

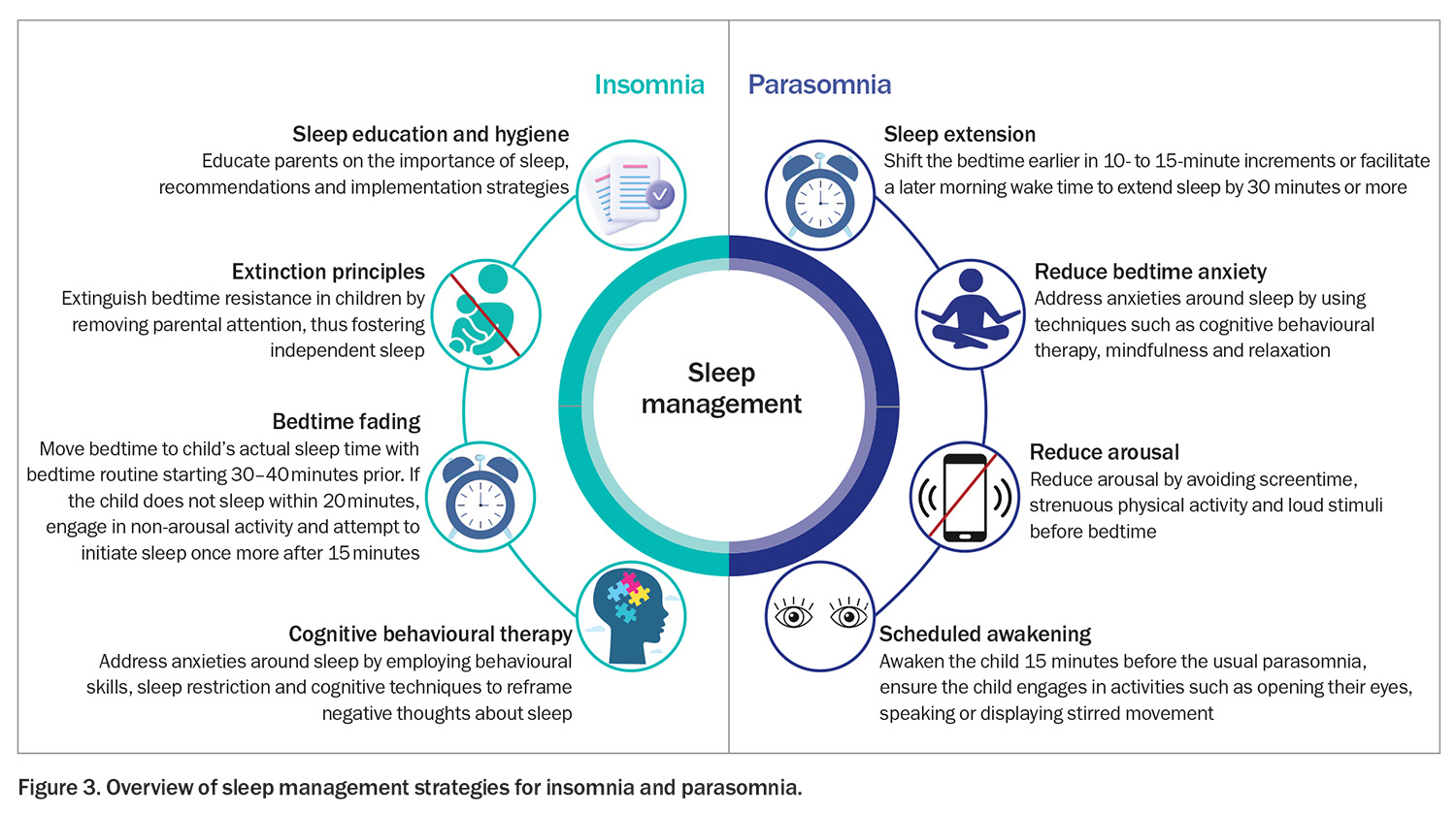

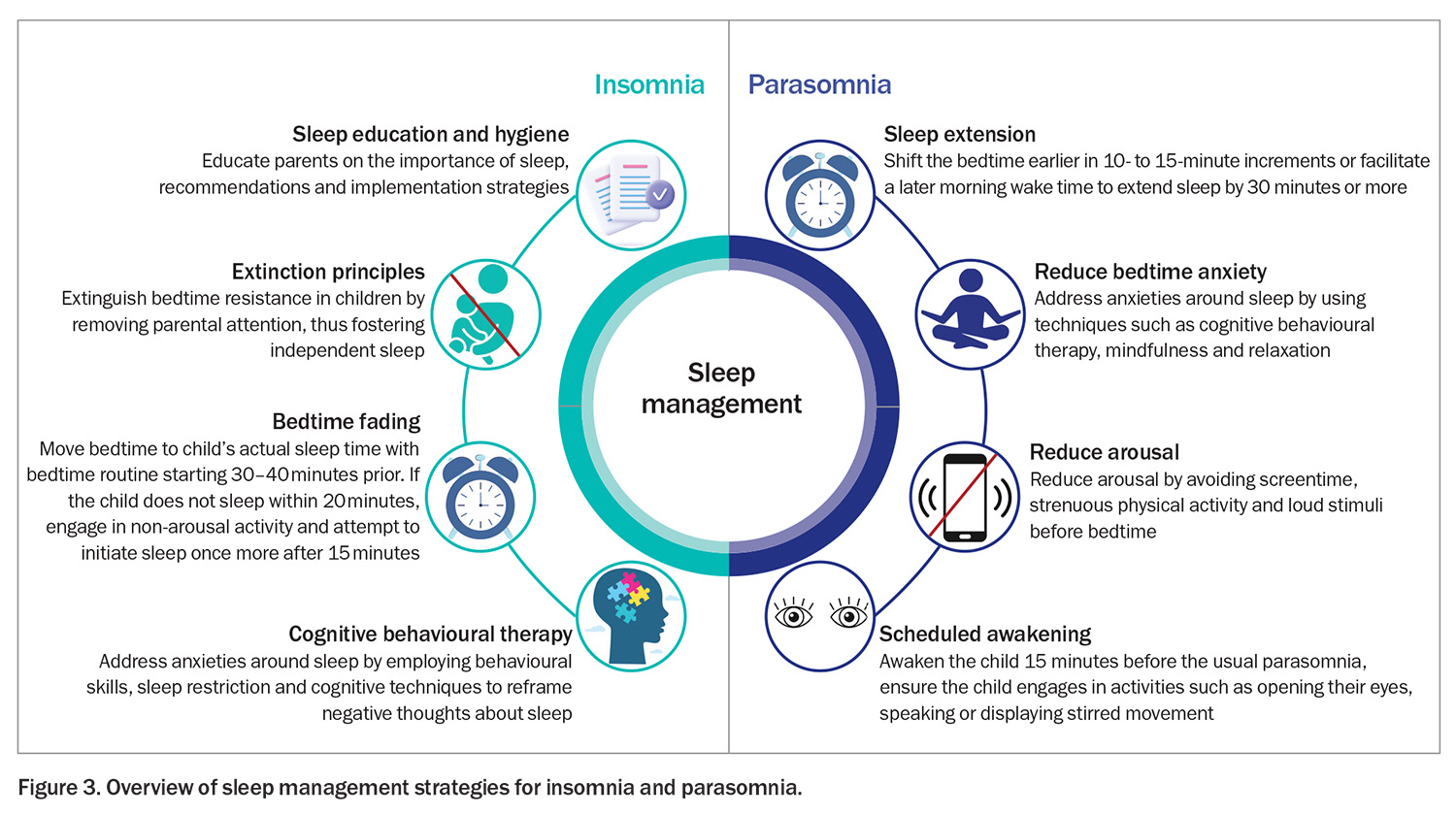

Insomnia can be managed using both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches. Nonpharmacological behavioural interventions are recommended as first-line treatment and are usually required to support pharmacological therapies. Meta-analyses of behavioural interventions have demonstrated their efficacy in treating issues related to night waking, sleep-onset delay and sleep efficiency in children.22,23 Examples of different strategies that can be used include extinction principles, bedtime fading or cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). The decision regarding which method to adopt should be discussed with the family to determine the optimal strategy for their child. Medications should be considered a short-term solution and used in conjunction with behavioural sleep strategies. Medications such as melatonin and clonidine have shown to be effective in improving sleep onset, sleep latency, total sleep time and sleep efficiency in select populations, but should be reserved for cases that do not resolve with first-line behavioural strategies.24,25 It is recommended that a paediatrician, psychiatrist or sleep specialist is involved if medications, such as clonidine, are required.

Sleep hygiene, sleep education and bedtime routines

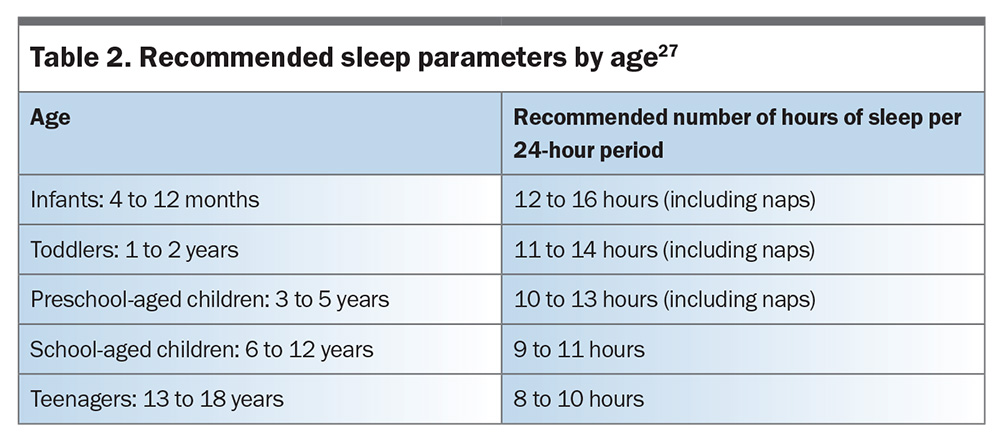

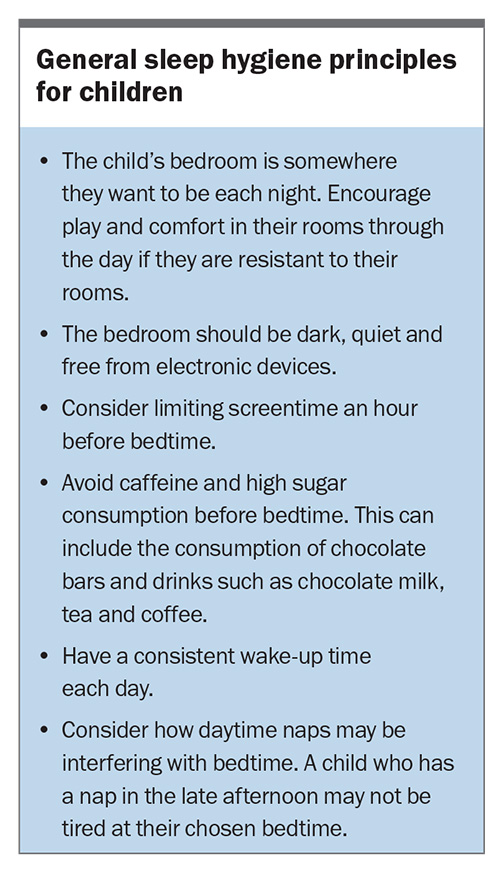

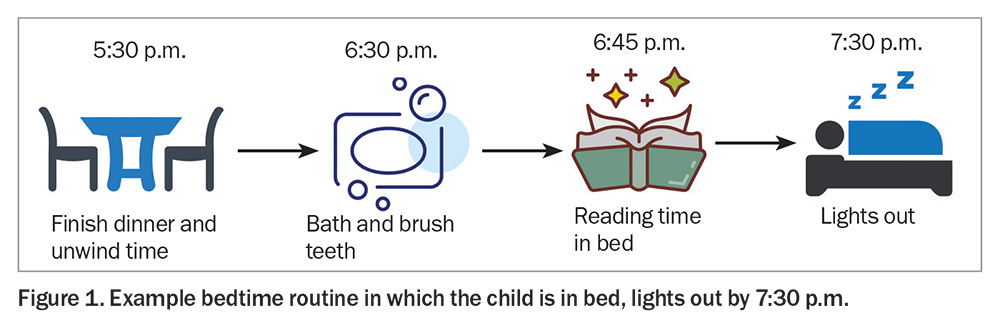

Sleep hygiene refers to a set of practices that support optimal sleep health, with particular attention paid to regular scheduling of sleep times. Sleep education and information about sleep hygiene are important first steps in managing insomnia. The aim is to educate parents on the importance of sleep to support health, cognition and achievement in their child and to advise on recommended sleep parameters (Table 2), along with providing easy-to-implement strategies.26,27 This information can be delivered by practitioners (including GPs, paediatricians or allied healthcare professionals) through education pamphlets and online information or in conjunction with further behavioural sleep interventions. Optimising sleep hygiene may also include addressing the sleep environment (dark, free of stimuli), controlling exposure to stimuli before bedtime and limiting caffeine consumption.28 Similarly, consistent and soothing routines before bedtime allow the child to associate a predictable sequence with sleepiness and sleep onset.29 General sleep hygiene principles can be found in the Box. An example bedtime routine can be found in Figure 1.

Extinction principles

Traditional extinction uses the idea that withdrawing parental attention, by ceasing to respond to a child’s cries or protests, will extinguish the child’s learned resistance to bedtime.29 By leaving the child alone, the child eventually learns to self-soothe and sleep on their own. Although this approach is abrupt, graduated extinction allows the methods behind these principles to provide more comfort to the child. Graduated extinction is a stepwise method that allows the parent to return to the room and provide unrewarding reassurance at set times, with the times between these parental attendances gradually extended. If the child attempts to leave their room, they are returned calmly with minimal interaction. Finally, extinction with parental presence allows the parent to remain in the room with the aim of gradually increasing the distance between the child and their parent. Requests for attention or physical contact are ignored by the parent until the child is sleeping without parental input. This technique may be tolerated better by children who are anxious around bedtime or who find change to routine or behaviours difficult or scary.29

Bedtime fading with and without response cost

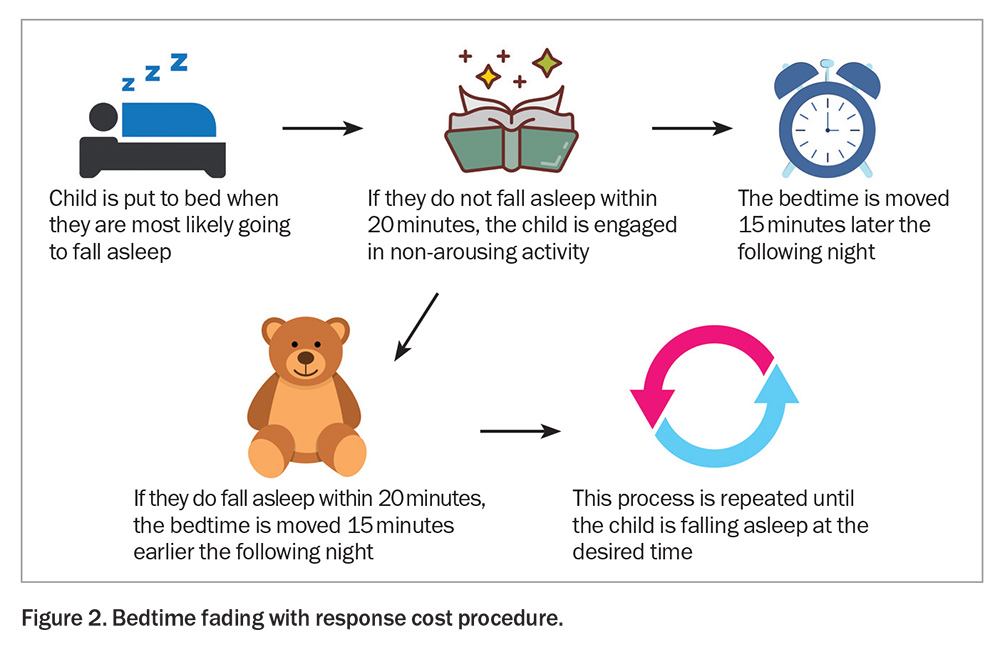

Bedtime fading has been shown to be effective in addressing a variety of sleep issues including night waking, early waking, bedtime tantrums and delayed sleep onset.30 This technique involves shifting the bedtime to approximately when the child is most likely to fall asleep. For example, if the usual bedtime is 6 p.m., but the child does not fall asleep until 9 p.m., the child is put to bed at 9 p.m. The bedtime routine is then commenced 30 to 40 minutes before the new bedtime. If the child is not asleep within 20 minutes, they are engaged in a non-arousing activity and the bedtime is delayed by 15 minutes the following night. If the child successfully falls asleep within 20 minutes, the bedtime is shifted 15 minutes earlier the following night.30,31 This is repeated at intervals of every few days up to a week until the bedtime is adjusted to the desired time (Figure 2).

Bedtime fading without response cost follows the same procedure without removing the child from their bed or engaging in activities when sleep does not occur. Restriction of sleep during waking hours (not inclusive of scheduled naps) assists in establishing quick and sustained sleep onset.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia

CBT-I has shown emerging efficacy in school-aged children for the treatment of insomnia.32 CBT-I combines behavioural skills and sleep restriction along with cognitive techniques of reframing negative thoughts around sleep to address any sleep-associated anxieties.24 Sleep restriction involves reducing the time the child spends awake in bed attempting to fall asleep.33 The first step is delaying the bedtime to a time they are likely to fall asleep quickly. For some children, it may involve setting and maintaining a consistent morning wake time. The goal is to reduce the time the child spends in bed and possibly worry, along with creating higher sleep drive. If the child’s sleep onset is within 30 to 45 minutes of going to bed, the bedtime fading strategy is employed to shift the bedtime back to the desired time.33 Although this is the first-line treatment in adults, there is limited evidence of its efficacy in paediatric populations, and it may not be appropriate for preschool-aged and younger children because of the concepts and cognitive skills required for complex cognitive therapy to be effective. However, these skills evolve from 7 years of age, and CBT-I has been found to be effective in school-aged children and adolescents.34,35 It is particularly effective in improving sleep anxieties and fears, sleep associations, sleep onset, sleep efficiency and waking after sleep in children and adolescents.34-36 Typically, four to six CBT-I sessions are needed to generate long-lasting change, and a referral to a psychologist with an understanding of sleep may be recommended. An overview of sleep management strategies for insomnia is presented in Figure 3.37

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are defined as undesirable events or experiences that occur during sleep.38 They can present as involuntary movement such as sleepwalking, periodic limb movement or experiential episodes, such as lucid dreaming or night terrors. These usually occur when the transitions between sleep stages are blurred, resulting in behaviours and experiences that lack awareness.5

Parasomnias can affect children at any age, but most commonly occur between the ages of 2 and 5 years, with some of the most common parasomnias affecting up to 50% of children before school age.5,39 Parasomnias are often hereditary, with children regularly ageing out of frequent episodes.40 The ICSD-3 divides parasomnias into six disorder groups emerging from either rapid eye movement (REM) or non-REM (NREM) sleep, with NREM disorders being the most common.5,41 NREM, REM and other parasomnias and how they may present are summarised in Table 3.39 NREM parasomnias are repeated occurrences of incomplete arousals, typically in the first part of the night. These are usually brief (lasting one to 10 minutes) but can last up to one hour in some cases.6 NREM parasomnias involve physical and verbal activity (sleepwalking or sleep terrors) with varying severities. In most cases, the child returns to sleep and is unaware of the occurrence in the morning, with the behaviour typically reported by those around them.40 Night terrors and confusional arousals can be distressing for parents with children exhibiting agitated behaviours, such as crying, screaming, calling out or thrashing around, while being unresponsive to parents’ attempts to console.42 Once the episode has passed, children will calm down and return to restful sleep. Parents should be supported and educated around parasomnias to ease concern.

Conversely, REM parasomnias are verbalisations and actions interpreted as dream enactment that usually wake the child. The child can often recall the details of the episode, including the dream and any actions.40

Diagnosis and assessment

Clinical history-taking remains an important tool in the diagnosis of parasomnias (Table 4).5,6 Assessment should include enquiry about the frequency of episodes and the timing, expression and form of the behaviour in the everyday home environment. A sleep history should be taken, as insufficient amounts of sleep can contribute to parasomnia symptoms. The presence of illness and fever and other lifestyle factors (e.g. stress, sleeping in new surroundings, temperature [particularly overheating], diet or other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnoea and periodic limb movement disorder) can exacerbate and trigger episodes.41 A medication history should also be obtained to ensure that parasomnias are not being exacerbated by specific treatments, such as antidepressants, some cardiovascular medications and some sleep medications (such as zopiclone and zolpidem).43

Sleep diaries or video recordings of the events can be helpful in determining the pattern and nature of the episodes and exclude other differential diagnoses. It is important to distinguish parasomnias, especially night terrors and confusional arousals, from an underlying seizure disorder, such as benign focal epilepsies or frontal lobe complex partial seizures that can occur during sleep.44,45 PSG, EEG or video footage can be helpful for distinguishing between conditions.14 Validated scales, such as the Frontal Lobe Epilepsy and Parasomnia (FLEP) scale, can also be used.46 The FLEP scale uses a series of specific questions based on the features of nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy and parasomnias to help distinguish between the two conditions.

Most children who experience parasomnias do not require referral to a specialist. Parents can be reassured and provided with simple advice to keep the child safe during the episode. Depending on the severity of parasomnia episodes, the events often decrease in frequency through childhood, with issues rectifying in one to two years.47 Parental education should be provided and, for less severe cases, education and support may suffice. In all cases, management strategies that ensure the safety of the child should be encouraged, such as moving the bed mattress onto the floor or adding locks onto doors to prevent the child from opening doors and latches while sleepwalking.47 Referral should be considered if diagnostic clarification is required or, in severe cases, if the frequency of events is leading to sleep disruption on a nightly basis and causing daytime dysfunction. Additional investigations are rarely required but may include PSG to exclude other differential diagnoses such as obstructive sleep apnoea or to diagnose REM parasomnias through the demonstration of REM sleep without atonia.5

Sleep management

The management strategies for parasomnias overlap with those for insomnia, including sleep hygiene, sleep education and bedtime routine principles. In more severe cases, strategies such as sleep extension, scheduled awakenings or psychotherapies and addressing bedtime anxiety can be effective in reducing the frequency of parasomnias.48

Sleep extension

Insufficient sleep has shown to increase the frequency of parasomnia episodes. By extending the child’s sleep duration, even by 30 minutes or more, can help to decrease these episodes. This can be achieved by using bedtime fading to shift the bedtime earlier in 10- to 15-minute increments or facilitating a later morning wake time.

Psychotherapies and reducing bedtime anxiety

If a child is in an aroused state at bedtime, this may exacerbate parasomnias. Avoidance of triggers, such as screentime, strenuous physical activity or loud stimuli before bedtime, will help to reduce arousal. If bedtime anxiety is evident, techniques such as cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness and relaxation can assist in promoting a gentle and calming pre-bedtime routine. This may require referral to a psychologist.

Scheduled awakenings

Scheduled awakenings can be useful for children who experience frequent and consistent parasomnias. It has been shown to be effective for children with chronic and severe sleepwalking and sleep terrors.49 Scheduled awakenings are thought to interrupt the cycle of spontaneous partial arousal in the child’s sleep to reduce the occurrence. Parents are asked to maintain a sleep diary over a two-week period and track the time of night the child’s parasomnia occurs, to help establish an awakening time. Parents gently awaken the child 15 minutes before the usual occurrence and ensure the child either opens their eyes, speaks to them or stirs. This is usually done until the frequency of episodes begins to reduce. An overview of sleep management strategies for parasomnia is presented in Figure 3.48

Conclusion

Sleep disturbances impact 30 to 40% of children before school age and can have profound impacts on emotional regulation and daytime functioning. Insomnia relates to issues with sleep initiation and maintenance with behavioural insomnia, reflecting behaviours and associations that might inhibit sleep or returning to sleep. Parasomnias are involuntary motor, autonomic or experiential episodes that occur during the transitioning of sleep stages. NREM and REM parasomnias represent differing presentations of behaviour within certain stages of sleep.

Both insomnia and parasomnias can be assessed through consultations with practitioners (including GPs, paediatricians and sleep specialists) with the use of history-taking and parental sleep diaries. Screening tools, such as the BEARS tool, can be used to guide sleep history-taking to gain specific knowledge. Parent-reported sleep questionnaires, such as the CSHQ and SDSC, can be used to aid diagnosis in specific populations.

Behavioural interventions have shown to be effective in the treatment of both parasomnias and insomnias and should be regarded as the first step in treatment. Effective pharmaceutical options are available, but these should be prescribed for use concurrently with behaviour modifications. If provision of the advice herein does not prove to be successful, or further investigation or treatment (including medications) is required, the child should be referred to a specialist sleep physician. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Spruyt K. A review of developmental consequences of poor sleep in childhood. Sleep Med 2019; 60: 3-12.

2. Iglowstein I, Jenni OG, Molinari L, Largo RH. Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 302-307.

3. Ophoff D, Slaats MA, Boudewyns A, Glazemakers I, Van Hoorenbeeck K, Verhulst SL. Sleep disorders during childhood: a practical review. Eur J Pediatr 2018; 177: 641-648.

4. Cooke E, Smith C, Miguel MC, Staton S, Thorpe K, Chawla J. Siblings’ experiences of sleep disruption in families with a child with Down syndrome. Sleep Health 2024; 10: 198-204.

5. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed, text revision. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Nevšímalová S, Bruni O. Sleep disorders in children. 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Cham; 2017.

8. Donskoy I, Loghmanee D. Insomnia in adolescence. Med Sci (Basel) 2018; 6: 72.

9. Owens JA, Mindell JA. Pediatric insomnia. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011; 58: 555-569.

10. Brown KM, Malow BA. Pediatric insomnia. Chest 2016; 149: 1332-1339.

11. Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Stability of sleep disorders from preschool to first grade and their bidirectional relationship with psychiatric symptoms. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2015; 36: 243-251.

12. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013; 36: 1059-1068.

13. Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev 2014; 18: 521-529.

14. Moturi S, Avis K. Assessment and treatment of common pediatric sleep disorders. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2010; 7: 24-37.

15. Owens JA, Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med 2005; 6: 63-69.

16. Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000; 23: 1043-1051.

17. Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, et al. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res 1996; 5: 251-261.

18. Australasian Sleep Association. Paediatric resources. Sydney: Australasian Sleep Association; 2020. Available online at: https://sleep.org.au/Public/Resource-Centre/F-HP-Info/Paediatric.aspx (accessed September 2024).

19. Smith MT, McCrae CS, Cheung J, et al. Use of actigraphy for the evaluation of sleep disorders and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2018; 14: 1231-1237.

20. Hyde M, O’Driscoll DM, Binette S, et al. Validation of actigraphy for determining sleep and wake in children with sleep disordered breathing. J Sleep Res 2007; 16: 213-216.

21. Pamula Y, Nixon GM, Edwards E, et al. Australasian Sleep Association clinical practice guidelines for performing sleep studies in children. Sleep Med 2017; 36: S23-S42.

22. Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. J Pediatr Psychol 2014; 39: 932-948.

23. Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, et al. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep 2006; 29: 1263-1276.

24. Badin E, Haddad C, Shatkin JP. Insomnia: the sleeping giant of pediatric public health. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016; 18: 47-47.

25. Barrett JR, Tracy DK, Giaroli G. To sleep or not to sleep: a systematic review of the literature of pharmacological treatments of insomnia in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2013; 23: 640-647.

26. Lunsford-Avery JR, Bidopia T, Jackson L, Sloan JS. Behavioral treatment of insomnia and sleep disturbances in school-aged children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2021; 30: 101-116.

27. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2016; 12: 785-786.

28. Posner D, Gehrman PR. Chapter 3 - Sleep hygiene. In: Perlis M, Aloia M, Kuhn B, eds. Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. p. 31-43.

29. Hill C. Practitioner review: effective treatment of behavioural insomnia in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011; 52: 731-740.

30. Kodak T, Piazza CC. Chapter 29 - Bedtime fading with response cost for children with multiple sleep problems. In: Perlis M, Aloia M, Kuhn B, eds. Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. p. 285-292.

31. Schreck KA. Clinical handbook of behavioral sleep treatment in children on the autism spectrum. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Cham; 2022. p. 137-150.

32. Dewald-Kaufmann J, de Bruin E, Michael G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) in school-aged children and adolescents. Sleep Med Clin 2019; 14: 155-165.

33. Cain N, Richardson C, Bartel K, Whittall H, Reeks J, Gradisar M. A randomised controlled dismantling trial of sleep restriction therapies for chronic insomnia disorder in middle childhood: effects on sleep and anxiety, and possible contraindications. J Sleep Res 2022; 31: e13658.

34. Paine S, Gradisar M. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy for behavioural insomnia of childhood in school-aged children. Behav Res Ther 2011; 49: 379-388.

35. Ma ZR, Shi LJ, Deng MH. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res 2018; 51: e7070.

36. Tikotzky L, Sadeh A. The role of cognitive–behavioral therapy in behavioral childhood insomnia. Sleep Med 2010; 11: 686-691.

37. McCrae CS, Chan WS, Curtis AF, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia in school‐aged children with autism spectrum disorder: a pilot feasibility study. Autism Res 2020; 13: 167-176.

38. Kumar H, Vardhan S. Chapter 41 - Other parasomnias. In: Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, Gozal D. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2014. p. 325-329.

39. Waters KA, Suresh S, Nixon GM. Sleep disorders in children. Med J Aust 2013; 199: S31-S35.

40. Fleetham JA, Fleming JAE. Parasomnias. CMAJ 2014; 186: E273-E280.

41. Singh S, Kaur H, Singh S, Khawaja I. Parasomnias: a comprehensive review. Cureus 2018; 10: e3807.

42. Stores G. Dramatic parasomnias. J R Soc Med 2001; 94: 173-176.

43. Bollu PC, Goyal MK, Thakkar MM, Sahota P. Sleep medicine: parasomnias. Mo Med 2018; 115: 169-175.

44. Panayiotopoulos CP, Michael M, Sanders S, Valeta T, Koutroumanidis M. Benign childhood focal epilepsies: assessment of established and newly recognized syndromes. Brain 2008; 131: 2264-2286.

45. Stores G, Zaiwalla Z, Bergel N. Frontal lobe complex partial seizures in children: a form of epilepsy at particular risk of misdiagnosis. Dev Med Child Neurol 1991; 33: 998-1009.

46. Derry CP, Davey M, Johns M, et al. Distinguishing sleep disorders from seizures: diagnosing bumps in the night. Arch Neurol 2006; 63: 705-709.

47. Marcus C, Carroll JL, Donnelly D. Sleep in children: developmental changes in sleep patterns. 2nd ed. UK: CRC Press; 2008. p. 253-272.

48. Mundt JM, Schuiling MD, Warlick C, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for NREM parasomnias: a systematic review. Sleep Med 2023; 111: 36-53.

49. Byars K. Chapter 34 - Scheduled awakenings: a behavioral protocol for treating sleepwalking and sleep terrors in children. In: Perlis M, Aloia M, Kuhn B, eds. Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. p. 325-332.