Allergen immunotherapy: when to consider for patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma

Allergen immunotherapy involves the regular administration of a commercially prepared extract of a substance that a person is allergic to. The aim is to blunt the immune response following allergen exposure. There is emerging evidence that immunotherapy can improve current allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma, and may also reduce the risk of developing new-onset asthma.

- Allergen immunotherapy aims to reduce the allergic inflammatory response following exposure to allergic triggers by deliberate exposure to commercially prepared allergen extracts.

- Currently available options in Australia include sublingual immunotherapy and subcutaneous immunotherapy injections.

- There is emerging evidence that immunotherapy can not only improve current allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma, but that its early use may also reduce the risk of developing new-onset asthma.

- The best evidence for benefit from immunotherapy is when symptoms are triggered by exposure to house dust mite and grass pollen.

- Barriers to accessing immunotherapy include knowledge of availability, access to specialist services, cost, limited availability of fully registered allergen extracts, inconvenience and adherence to maintenance therapy.

- Allergen immunotherapy is usually prescribed and initiated by specialists with training in allergic disease, with maintenance therapy supervised in the primary care setting.

Australian health surveys indicate that about 10.8% of people in Australia are affected by asthma and about 20% are affected by allergic rhinitis, which is the most common in teenagers and young adults.1 Allergic rhinitis alone has a significant impact on quality of life, sleep quality and academic performance, and has a measurable economic cost in terms of unsubsidised medication use, absenteeism and ‘presenteeism’. Individuals who are allergic to grasses or animals may limit their outdoor and social activities, and at times the latter may have a significant impact on their psychological wellbeing and occupation (e.g. laboratory or veterinary work).2-5

The role of dust mite immunotherapy in helping people with atopic eczema is controversial, with a 2016 Cochrane analysis suggesting no convincing benefit, but a more recent systematic review in 2023 suggesting moderate benefit.6,7 Interpretation of these studies is made more difficult given that many are small studies of variable quality, using a wide variety of different allergen extracts and methods. Nonetheless, consideration of adding immunotherapy in patients with moderate to severe atopic eczema who are also sensitised to house dust mite is starting to make its way into some treatment guidelines. The specific focus of this article is the role of immunotherapy for the treatment of allergic respiratory disease. Food immunotherapy is beyond the scope of this article.8

Natural history of allergic rhinitis and asthma

To anticipate the natural resolution of allergic rhinitis is an overly optimistic approach. In long-term follow-up studies, 45% of American university students were still symptomatic 23 years later, 65% of adults with allergic rhinitis developed additional allergies over the next decade and 32% developed new asthma.9,10 Among children with pollen allergy, 75% were still symptomatic and 30% developed asthma after 20 years’ follow up.11 Although 75% of children with asthma will undergo spontaneous resolution, adults are much less likely to do so, and the presence of allergic rhinitis and allergy or sensitisation to food are major risk factors for persistent asthma and development of new asthma.12-15

Avoiding allergic triggers

Allergen minimisation strategies are often recommended but are only occasionally successful. It is difficult to reduce pollen exposure without staying indoors. Under some circumstances, pollen can be transported hundreds of kilometres, and a warming climate with higher CO2 levels has been associated with longer pollen seasons and more intense exposure.16,17 Drying bedding indoors in the spring (e.g. in a clothes dryer) and removal of causative trees near the house might have some modest benefit. Mould spores are constantly in the air, and apart from removing overt sources of indoor mould and pot plants, little else can be done. House dust mite allergy is a major risk factor for persistent asthma; however, the effectiveness of avoidance strategies is also controversial, with low levels of house dust mite allergens very difficult to achieve in most studies following hot washing of bedding, carpet removal and use of dust mite-impermeable covers.18

Finally, allergy to domestic pets is also common, even in people without exposure at home. Rehousing pets is the only effective option for those with significant animal allergy and, even then, pet allergens take 6 to 12 months to degrade naturally. Use of recombinant anti-Fel d1 immunoglobulin (Ig)Y antibodies added to commercial cat food has been shown to reduce Fel d1 excretion in cat saliva and hair, but its clinical effectiveness remains to be proven in controlled studies.19,20 Strategies like cleaning the house, removing pets from bedrooms and use of high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters have shown no convincing evidence of clinical benefit, even when lower levels of allergens have been achieved.21,22 Exposure to allergens may occur outside the home, such as at sleepovers or in schools and childcare centres, even when pets are absent. In addition, many individuals will be clinically allergic to multiple triggers such that complete symptomatic control is unlikely and, even if allergic rhinitis improves, asthma control is even harder to achieve with allergen minimisation strategies alone.23

It is important to be aware that obscure or novel allergen sources may sometimes need to be considered. For example, use of cannabis in various forms is reported by 23% of adults in Australia aged 20 to 29 years and 11.5% of people in Australia overall. Cannabis has been reported as a novel inhalant allergen, triggering allergic rhinitis and asthma (including occupational exposure). Allergen cross-reactivity can occur with foods such as tomato, peach and hazelnut, triggering oral allergy syndrome, and anaphylaxis has been reported from orally ingested or injected hemp seed.24,25

Pharmacological treatment

The role of medication for the treatment of asthma and allergic rhinitis has been summarised in a number of related articles in Medicine Today and Respiratory Medicine Today.26-28 Symptomatic control is often suboptimal, related in part to self-diagnosis and treatment without medical advice, or lack of use of more effective medications such as intranasal corticosteroids and asthma preventers compared with ‘reliever’ medications such as antihistamines or asthma bronchodilators.29-31 Even with diligent use of medication, not all patients will achieve adequate control and relapse occurs once treatment is withdrawn. Allergy medicines are very safe (significant side effects are very rare), enabling prolonged use in the vast majority, but there is often resistance among patients to taking regular medication. This can occur because of patients’ view that they are ‘only’ treating an allergy, despite the disability that can result from severe undertreated disease.

Allergen immunotherapy: a brief history

Allergen immunotherapy involves the regular administration of a commercially prepared extract of a substance that a person is allergic to (allergen). The aim is to blunt the immune response following allergen exposure. It was first described by Leonard Noon in 1911, when subcutaneous injections of grass extracts were found to reduce the severity of ‘spring catarrh’. The first allergen immunotherapy double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were described in 1954. In 1978, the benefit from immunotherapy was shown to be allergen-specific, such that immunotherapy directed against one trigger did not improve allergic reactivity to another unrelated trigger, as recently reviewed.32 Subsequent trials of subcutaneous immunotherapy injections (SCIT), and, later, sublingual oral immunotherapy tablets (SLIT), showed that long-term symptomatic control occurred for at least three years after treatment cessation, if the treatment duration was at least two to three years, providing a rationale for recommendations about the duration of maintenance therapy.32

Allergen extracts are natural products

Although there have been published trials of allergen peptide immunotherapy, and the future may bring production of highly purified recombinant allergen extracts, current allergen extracts are natural products. Collected pollen is normally dried and sieved to remove contaminating material; its species and purity are then checked via microscopy, followed by cleaning and aqueous extraction of protein. Glycerol and phenol are normally added to stabilise and preserve the extracts. Animal allergens are present in saliva, urine and blood, and are secreted in sebaceous glands. Animal extracts are prepared by shaving the animal (without harming the animal) to obtain raw material containing a combination of hair and shed skin (dander). These are then sieved, treated with acetone to remove fat, followed by aqueous extraction of water-soluble allergen and processed as above. House dust mite and mould extracts are grown in tissue culture and subject to similar extraction procedures. Sterility testing is undertaken for all extracts.

Most extracts are standardised according to their protein concentration but not necessarily their allergen concentration. ‘Standardised extracts’ are assessed by measuring their biological potency (generally an assessment of the results of skin allergy testing) and will list some measure of an in-house index of biological potency. Nonstandardised extracts do not undergo this process.33

When to consider immunotherapy

Allergen immunotherapy has been shown to reduce the severity of symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma (including thunderstorm asthma) and may help selected individuals with atopic eczema. It has not been shown to alter the natural history of nasal polyps.

Allergen immunotherapy can be considered when an allergic origin for symptoms of asthma or allergic rhinitis is likely. The diagnosis is based on the history, symptoms that occur with provocation and clinical examination findings, and is confirmed by the detection of clinically relevant allergen-specific IgE (e.g. skin prick or blood allergy testing). Importantly, a diagnosis cannot be based on results of allergy testing alone, as sensitisation may be detectable in individuals where an allergy is not the cause of symptoms (e.g. blepharitis as a cause of ocular discomfort or nasal congestion from nasal polyps or chronic sinusitis).

Other factors that may warrant consideration of allergen immunotherapy include the following:

- patient difficulty avoiding allergen triggers (e.g. pollen, occupational animal exposure) or patients who do not wish to avoid their triggers (e.g. domestic pet allergies)

- poor medication adherence, ineffective treatment, side effects from medications or high cost of medications

- patient preference: an individual may prefer to treat the cause rather than rely on medication, knowing that medication is not curative, and that successful immunotherapy may be more cost effective than medication taken for decades.

Specific allergic triggers

When embarking on a course of immunotherapy, informed consent about the possible benefit is paramount. Patients need to be informed that there is high-quality evidence that dust mite and grass pollen immunotherapy is effective. They also need to be aware that the evidence base for benefit from immunotherapy targeting mould is absent, and for domestic animals is limited to small and, at times, conflicting studies, as discussed below.

The small print: how immunotherapy works

There are two broad phases to the allergic response. First, there is an initial recognition of allergens by mast cells in the tissues primed by allergen-specific IgE on mast cells and basophils, with accompanying mediator release (histamine and leukotrienes, among others). This initial phase is responsible for early symptoms such as itchy eyes and sneezing soon after exposure. Subsequently, there is a delayed inflammatory response, and recruitment and activation of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils and lymphocytes into the tissues. Both SCIT and SLIT result in similar changes: production of IgG4 ‘blocking antibodies’ (with a more long-term reduction in allergen- specific IgE) and inhibition of the delayed inflammatory response (likely because of the development of suppressor T cells), and suppression of a type II pro-allergic immune response by stimulation of a suppressive type I immune response instead.32,34,35

Immunotherapy options for respiratory allergy

Although novel immunotherapeutic routes have been described (e.g. epicutaneous patches or allergen injections into lymph nodes or even tonsils), the only options available at this time are:

- SLIT using oral liquids (nonregistered, broad selection of allergens available, longer history of use)

- SLIT using standardised and fully registered grass or house dust mite tablets

- subcutaneous injections (SCIT), for which no fully registered extracts are available at the time of writing, although this situation may change in the future.35,36

For individuals in whom dust mite or grass pollen is the major cause of their allergic symptoms, there is no clinical advantage of trying SCIT first before registered SLIT tablets, other than cost or patient preference.

Immunotherapy injections (SCIT)

There are three different types of preparations with different properties available for SCIT: injectable aqueous extracts (more commonly used in the USA than in Australia and New Zealand), allergens bound to aluminium salts (which slow absorption, add a margin of safety and act as adjuvants to boost the immune response) and polymerised extracts (‘allergoids’), (which are considered to be safer because of lower IgE binding). Unfortunately, comparative studies comparing effectiveness are not available, although the first two types have a longer history of use. Aqueous formulations and aluminium hydroxide conjugated products are administered by subcutaneous injection, slowly building up the dose over two to three months until a maintenance dose is achieved. Use of allergoid SCIT is similar, except only a few doses are required before an ongoing maintenance dose is achieved. Once a maintenance dose is achieved, ongoing immunotherapy for another three to five years is recommended. This is because a longer duration of maintenance is associated with greater persistence of benefit.37 At the time of writing, no fully registered extracts for injectable use are currently registered in Australia or New Zealand. They can be imported for use on a ‘named patient’ basis, but this brings with it the absence of local supplies, and the need for significant organisational ability for patients and their doctors to import extracts in a timely fashion to start and reorder to continue therapy without interruption.

Sublingual (oral) immunotherapy (SLIT)

SLIT oral liquids were introduced into clinical use in Australia and New Zealand around 2015, with a broad range of allergen extracts available, but the absence of full registration means that they need to be imported on a named-patient basis, just like SCIT extracts. Their use has largely been superseded by fully registered and standardised grass and house dust mite tablets, which have been available in Australia and New Zealand for over 10 years. These tablets have a high-quality evidence basis of benefit, and their full registration status locally and abroad means that local supplies are easy to obtain and facilitates the possibility of obtaining private health rebates to subsidise cost if a patient has the appropriate private health insurance cover.

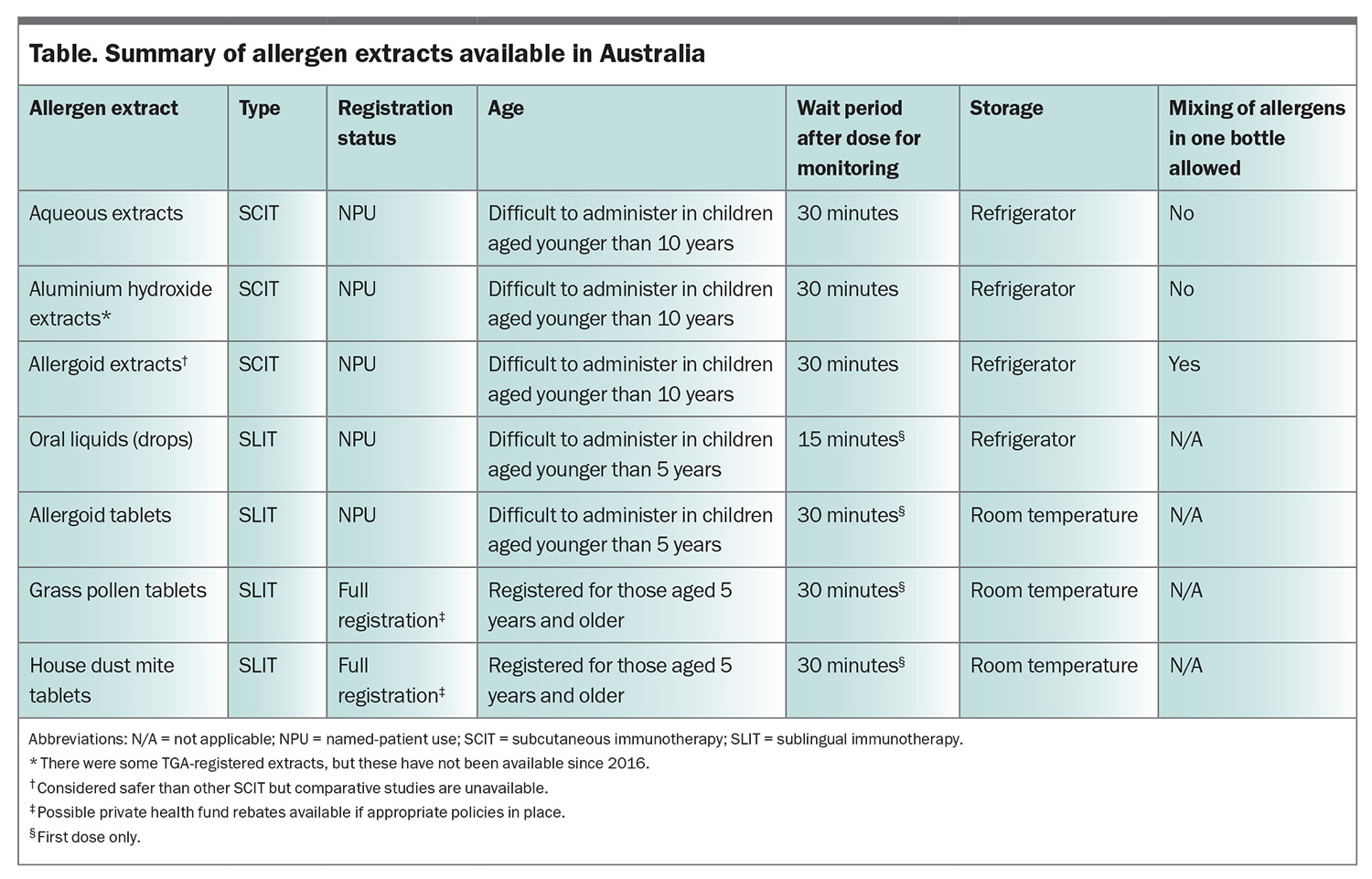

Cost, logistical issues and allergen selection

No aeroallergen immunotherapy extract is subsidised on the PBS, although private rebates may be available for TGA-registered products (only fully registered tablets at this time). There is, however, a Medicare subsidy for medical consultations associated with both SCIT and SLIT. The available allergen extracts, and their advantages and disadvantages, are summarised in the Table. It is important to be aware that individuals will usually benefit from the use of standard grass pollen tablets or SCIT even if sensitised to additional pollen allergens not contained in those extracts.38 Second, it is possible (and common practice) to undertake immunotherapy directed against more than one unrelated target at the same time (e.g. dust mite and pollen), although the evidence basis for this approach is limited.39 If undertaking SCIT against unrelated allergic triggers, these should be administered as separate injections, as mixing non-allergoid SCIT extracts in the same bottle is discouraged because of the risk of enzyme degradation (such that extracts lose potency by mixing because of autodigestion) and dilution of concentration (reducing effectiveness). The selection of the important immunotherapy targets is based on a clinical assessment of the likely allergen(s) causing symptoms, confirmed by the results of skin or blood allergy testing. Patients need to be made aware that the evidence for immunotherapy directed against animal allergens is relatively poor (based on small trials with conflicting evidence of benefit). It can certainly be tried as an alternative to rehousing pets, but may be of limited benefit, in part because of the poor standardisation of extracts.40-42 Similar comments apply to mould immunotherapy.43,44

Benefits of immunotherapy for treating allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma

Controlled studies have shown improvement in symptoms of allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, and a reduction in the need for allergy-related medication in adults and children, as recently reviewed.34,35,37,45 Benefit has been demonstrated for immunotherapy injections and SLIT tablets, with a less convincing benefit for SLIT using oral liquids.34 Similar changes have been observed in the treatment of asthma, although without significant changes in objective measures of lung function.34,46 Nonrandomised observational studies have also shown benefit following grass tablet SLIT in reducing the risk of thunderstorm asthma.47,48 In considering the benefit for immunotherapy for asthma, it is important to be aware that allergy is only one potential aggravating factor for asthma, that infection and exposure to irritants may lead to exacerbations, and that so-called type II inflammation may occur independent of allergy. Treatment duration of three to five years is recommended, and studies showed sustained benefit after treatment cessation for at least three years. Benefit is often seen within the first few months of treatment, although most patients will continue to improve in their second and third year, and the lack of initial benefit does not mean that improvement will not occur with longer duration.34,37

Can immunotherapy prevent new asthma?

Emerging evidence has shown that immunotherapy for aeroallergens may reduce the risk of developing new sensitisations and new asthma as well as improve existing asthma.49-52 The GAP study enrolled 812 children with grass allergy aged between 5 and 12 years of age and allocated them to either standard oral grass tablet immunotherapy or placebo. Seventy-five percent of the children completed the study and follow up occurred two years after study completion. Substantial benefit was observed among participants in the immunotherapy arm in terms of allergic rhinitis severity and a reduction in the proportion of new asthma development from 20% on placebo tablets to 15% in those on active treatment (odds ratio 0.66).53 A related longer follow-up study demonstrated the benefit of earlier initiation of grass tablets (SLIT), with initiation at ages 5, 7 and 12 years resulting in rates of development of new asthma of 19%, 24% and 29%, respectively, over the subsequent 20 years.54

A dust mite immunotherapy trial in 111 high-risk babies aged 5 months allocated them to dust mite tablets or placebo for 12 months. When assessed at the age of 6 years, participants in the intervention arm had a reduction in dust mite sensitisation from 45% to 28%, and a reduction in definite asthma from 13.5% to 2.9%.55

Barriers to undertaking immunotherapy

Unfortunately, adherence to maintenance treatment of immunotherapy is poor, with only 30 to 50% completing at least three years of maintenance treatment.56,57 Reminder systems may improve adherence to review and duration, albeit imperfect. Other barriers to immunotherapy are the absence of local manufacturers and, with the exception of fully registered tablets, no domestically held supplies. This results in the need to import all SCIT and SLIT liquids on a named-patient basis, which generally take a couple of months to arrive from overseas. The implication is that careful planning is required to prevent interruptions to treatment. By contrast, oral tablet immunotherapy may be purchased at any local pharmacy on prescription, facilitating access. Other barriers to undertaking successful immunotherapy include:

- failure to commence immunotherapy at all

- failure to return for review

- failure to continue immunotherapy

- inconvenience of associated time off work to attend starting dose appointment (all) and for each SCIT dose

- associated cost (no PBS subsidy; higher cost if targeting more than one allergen at a time)

- adverse reactions

- lack of perceived benefit

- unrealistic expectations of benefit (e.g. expectations of cure vs improvement).

Who should prescribe allergen immunotherapy?

Allergen immunotherapy is usually prescribed and initiated by paediatricians or physicians (and sometimes trained GPs with an interest in allergy/immunology) who have undergone training in allergy. Prior to immunotherapy prescription, the initial assessment of patients includes skin prick or blood allergy testing, which optimises patient selection, education about their allergy triggers and immunotherapy, and enhances the likelihood of benefit from treatment.50 Most injections are administered in primary care. By contrast, SLIT is patient-administered at home after the first dose.

Contraindications and precautions

Pregnancy

If a patient is pregnant or planning pregnancy in the near future, commencement of SCIT is best deferred, owing to the risk of systemic allergic reaction that may affect a developing fetus; SLIT has a larger margin of safety and could be commenced if a patient is not yet pregnant. There is no evidence that immunotherapy causes fetal malformations, so if a patient is stable on SCIT or SLIT, there is no need to stop therapy. There is also no need to avoid immunotherapy in breastfeeding mothers.

Comorbidities and other precautions

Practitioners should be aware of the following additional considerations when prescribing allergen immunotherapy.

- Poorly controlled asthma, advanced age and cardiovascular disease may all have an impact on the safety of allergen immunotherapy and should be considered before initiating treatment.

- Autoimmune disease, malignancy and immune deficiency are often mentioned as a relative contraindication to allergen immunotherapy in product information sheets. There is no convincing evidence that affected individuals are at increased risk of adverse reactions or exacerbation of underlying disease, and such patients can be reassured that they can commence treatment if they wish.

- Patients with arm lymphoedema (e.g. after cancer surgery) should receive injections on the nonaffected side.

- SLIT may be considered in patients who have had anaphylaxis to SCIT; however, it must be initiated with caution as anaphylaxis to SLIT (although extremely rare) has been described.

- Eosinophilic oesophagitis is a contraindication to SLIT because of the risk of disease exacerbation. SCIT is considered to be the only realistic option for patients with this condition.

- Beta blocker use, especially nonselective beta blockers, may impede the management of anaphylaxis, so beta blockers are best avoided if allergen immunotherapy is prescribed, especially SCIT.

Practical and safety aspects of SCIT

SCIT is administered as deep subcutaneous injections, halfway between the shoulder and elbow over the deltoid region. Ideally, a 26- or 27-gauge diabetic needle and syringe should be used without dead space. Local itching and swelling are common and can be reduced by antihistamines taken before each injection. Vigorous exercise within two to three hours of an injection is discouraged because delayed systemic reactions may be triggered by physical exertion. Doses are best deferred if the patient has a fever, infectious illness or unstable asthma at the time. Local side effects, such as local itch and swelling, are common and can usually be managed by taking antihistamines before doses are given. Influenza-like symptoms after injections are rare but may prompt cessation in some cases. The rare risk of serious reactions (e.g. delayed asthma, rash or even anaphylaxis) underpins the standard recommendation for a 30-minute waiting period, under observation in the clinic waiting room, so that these can be recognised and treated if they arise. For this reason, a person with the skills and equipment to treat anaphylaxis must be available in any facility in which immunotherapy injections are administered. It is usually difficult to undertake SCIT in young children, although the application of a local anaesthetic patch one hour before treatment may improve tolerance.

Practical and safety aspects of SLIT

SLIT tablets or drops are administered under the tongue, retained for two minutes, then swallowed. Patients are advised to not eat or drink for five to 10 minutes afterwards. Studies have shown that if this practice is followed, the allergen remains in the mouth for a couple of hours (rather than being washed into the stomach), interacting with local dendritic cells. Most side effects are local, manifesting as brief, transient, local itch and swelling, which usually subside after the first couple of weeks of treatment. Tablets appear to be more potent than drops in causing such side effects. A 30-minute wait period in the doctor’s surgery is recommended after the initial dose, in case tongue or throat swelling occurs. Other doses are patient-administered at home. Antihistamines taken on a regular basis for the first couple of weeks usually improves tolerance. If mild gastrointestinal side effects continue, anecdotally, sometimes spitting out the allergen (instead of swallowing) may improve tolerance. If there are ongoing side effects, such as stomach pain, indigestion, severe tongue or throat swelling, or if eosinophilic oesophagitis occurs, treatment should be ceased. If an individual is prescribed two tablets, these can normally be taken at the same time to improve treatment adherence.

The major advantages of oral treatment are the ability to start immunotherapy in young children, room temperature storage of some preparations (tablets) and convenience. The major downside is its greater cost. The dose of oral allergen needed to alter an immune response is much greater than that required for subcutaneous therapy, so the cost of SLIT can be higher than the cost of SCIT, especially if allergen immunotherapy directed against multiple targets is simultaneously undertaken.

Assessment of benefit

Assessment of benefit is largely subjective, based on patient perception of reduced frequency and severity of symptoms and reduced need for medication upon exposure to allergic triggers. Various scoring systems, such as the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT scores) and the Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test (CARAT), are available to provide some objectivity in assessing benefit.58,59 Repeat allergy testing does not have a role in the assessment of benefit from immunotherapy, because the results of skin prick tests usually remain positive even after successful immunotherapy with substantial symptom relief. Generally, review may occur in the first six to 12 months of treatment and, if shown to be effective, treatment should be continued for a total of at least three years. Unfortunately, follow-up studies suggest a disappointing rate of three-year treatment adherence of as little as 30%.

If there is no significant improvement in the first to six to 12 months, it is reasonable to continue and re-assess a year later. When assessing benefit, it is also useful to determine which symptoms improve and which do not (e.g. improvement in sneeze, itch and ocular irritation but not nasal congestion due to nasal septal deviation).

What if immunotherapy does not work?

If treatment is ineffective, options that can be considered include the following:

- ongoing medication

- longer duration of treatment (shown to have greater accumulative benefit for SLIT and SCIT in years 2 and 3)

- changing from SLIT to SCIT or vice versa (but there is no evidence base for such an approach)

- considering whether a new allergy has developed (e.g. arrival of a new domestic pet)

- revisiting the diagnosis (e.g. erroneous diagnosis of allergy based on testing alone)

- considering whether nonallergic factors (e.g. intercurrent nonallergic rhinitis, nasal anatomy or sinusitis) might be contributing.34,37

Of course, no treatment is 100% effective in 100% of individuals.

Which is better: SCIT or SLIT?

Anecdotally, some patients appear to do better using one method rather than another but there are few studies directly comparing tablets and injections in the same trial and these are too small (about 20 to 30 subjects) to show any meaningful difference.34,45 The evidence base for SLIT (especially for tablets) is more recent and of much higher quality than that for SCIT, probably because of better allergen standardisation and much higher doses administered.34 Meta-analyses comparing the two methods have not been able to demonstrate superiority of one method over another.60 Nonetheless, for an individual in whom dust mite or grass pollen is the major cause of their allergic symptoms, there is no clinical advantage of trying SCIT first before fully registered SLIT tablets, other than cost or patient preference.

When to refer for immunotherapy

The primary reasons to refer a patient for allergy assessment are in the presence of difficult-to-control symptoms of allergic rhinitis and asthma (including thunderstorm asthma), in cases where the cause is difficult to avoid, when multiple regular medications are required to control allergic respiratory disease or in the presence of complex multisystem allergic disease. Nonetheless, even patients with mild symptoms should be made aware that there are therapeutic options available beyond medication, such that if symptoms worsen, the option of immunotherapy can be revisited. Useful information in a referral to an allergy specialist includes the treatments tried, suspected triggers, information on comorbidities (e.g. asthma, atopic eczema or food allergy) and results of allergy testing (e.g. house dust mite, Alternaria mould, grass mix or ryegrass, and pets, if relevant, and the tests undertaken).

Conclusion

In summary, decision making about immunotherapy for patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis first involves:

- deciding whether or not to proceed to immunotherapy or continue avoidance strategies and medication management

- if yes, deciding on which allergens to target following clinical assessment, including allergy testing

- deciding on method (SCIT or SLIT), which determines the cost and convenience of treatment.

The major barriers to successful immunotherapy are poor rates of adherence and the associated cost. Free e-training on allergen immunotherapy and management of allergic rhinitis is provided by the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (https://etraininghp.ascia.org.au/).61,62 RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Mullins has received payment for consulting services as a member of the Advisory Board for Seqirus; has been a member of education and anaphylaxis committees for ASCIA; has been a member of Insect Allergy and Drug Nomenclature committees for NACE; and has been a member of the Safety Monitoring Board for the PEBBLES study.

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). National Health Survey. Canberra: ABS; 2022. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey/latest-release#health-conditionsrelease (accessed August 2024).

2. Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith P, Abramson M, et al. Impact of allergic rhinitis on the day-to-day lives of children: insights from an Australian cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e038870.

3. Blaiss MS, Hammerby E, Robinson S, Kennedy-Martin T, Buchs S. The burden of allergic rhinitis and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis on adolescents: a literature review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 43-52.

4. Dávila I, Domínguez-Ortega J, Navarro-Pulido A, et al. Consensus document on dog and cat allergy. Allergy 2018; 73: 1206-1222.

5. Martin WE, Darcey DJ, Stave GM. Prevention of laboratory animal allergy and impact of COVID-19 on prevention programs in the United States: a national survey 10-year update. J Occup Environ Med 2023; 65: 443-448.

6. Tam HH, Calderon MA, Manikam L, et al. Specific allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of atopic eczema: a Cochrane systematic review. Allergy 2016; 71: 1345-1356.

7. Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Guyatt GH, Gómez-Escobar LG, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023; 151: 147-158.

8. Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Guyatt GH, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023 ; 151: 147-158.

9. Greisner WA 3rd, Settipane RJ, Settipane GA. Natural history of hay fever: a 23-year follow-up of college students. Allergy Asthma Proc 1998; 19: 271-275.

10. Lombardi C, Passalacqua G, Gargioni S, et al. The natural history of respiratory allergy: a follow-up study of 99 patients up to 10 years. Respir Med 2001; 95: 9-12.

11. Lindqvist M, Leth-Møller KB, Linneberg A, et al. Natural course of pollen-induced allergic rhinitis from childhood to adulthood: a 20-year follow up. Allergy 2024; 79: 884-893.

12. Ernst P, Cai B, Blais L, Suissa S. The early course of newly diagnosed asthma. Am J Med 2002; 112: 44-48.

13. Bronnimann S, Burrows B. A prospective study of the natural history of asthma. Remission and relapse rates. Chest 1986; 90: 480-484.

14. Biagini Myers JM, Schauberger E, He H, et al. A pediatric asthma risk score to better predict asthma development in young children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143: 1803-1810.

15. Peters RL, Soriano VX, Lycett K, et al. Infant food allergy phenotypes and association with lung function deficits and asthma at age 6 years: a population-based, prospective cohort study in Australia. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2023; 7: 636-647.

16. Maya-Manzano JM, Fernández-Rodríguez S, Smith M, et al. Airborne Quercus pollen in SW Spain: identifying favourable conditions for atmospheric transport and potential source areas. Sci Total Environ 2016; 571: 1037-1047.

17. Anderegg WRL, Abatzoglou JT, Anderegg LDL, Bielory L, Kinney PL, Ziska L. Anthropogenic climate change is worsening North American pollen seasons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021; 118: e2013284118.

18. Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TAE. Home environmental interventions for house dust mite. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 1-7.

19. Sulser C, Schulz G, Wagner P, et al. Can the use of HEPA cleaners in homes of asthmatic children and adolescents sensitized to cat and dog allergens decrease bronchial hyperresponsiveness and allergen contents in solid dust? Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2009; 148: 23-30.

20. Satyaraj E, Wedner HJ, Bousquet J. Keep the cat, change the care pathway: a transformational approach to managing Fel d 1, the major cat allergen. Allergy 2019; 74: 5-17.

21. Bousquet J, Gherasim A, de Blay F, et al. Proof-of-concept study of anti-Fel d 1 IgY antibodies in cat food using the MASK-air app. Clin Transl Allergy 2024; 14: e12353.

22. Maya-Manzano JM, Pusch G, von Eschenbach C E, et al. Effect of air filtration on house dust mite, cat and dog allergens and particulate matter in homes. Clin Transl Allergy 2022; 12: e12137.

23. Leas BF, D’Anci KE, Apter AJ, et al. Effectiveness of indoor allergen reduction in asthma management: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 1854-1869.

24. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol/alcohol-tobacco-other-drugs-australia/contents/drug-types/cannabis (accessed August 2024).

25. Decuyper II, Van Gasse AL, Faber MA. Exploring the diagnosis and profile of cannabis allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 983-989.

26. Lee AYS, Patel MN, Douglass JA. Allergic rhinitis: an update on management. Respiratory Medicine Today 2019; 4: 14-20.

27. Crawford A, Blakey JD, Chung LP. Severe asthma: what’s new in management? Respiratory Medicine Today 2024; 9: 29-32.

28. Wagner C, Douglass J. Evolving therapies for severe asthma: the role of the GP. Medicine Today 2017; 18: 14-20.

29. Bosnic-Anticevich S, Kritikos V, Carter V, et al. Lack of asthma and rhinitis control in general practitioner-managed patients prescribed fixed-dose combination therapy in Australia. J Asthma 2018; 55: 684-694.

30. Tan R, Cvetkovski B, Kritikos V. Identifying the hidden burden of allergic rhinitis (AR) in community pharmacy: a global phenomenon. Asthma Res Pract 2017; 3: 8.

31. Tan R, Cvetkovski B, Kritikos V. The burden of rhinitis and the impact of medication management within the community pharmacy setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 1717-1725.

32. Durham SR, Shamji MH. Allergen immunotherapy: past, present and future. Nat Rev Immunol 2023; 23: 317-328.

33. Goodman, Richard E, Slater JE. The allergen: sources, extracts, and molecules for diagnosis of allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 2506-2514.

34. Creticos PS, Gunaydin FE, Nolte H, Damask C, Durham SR. Allergen immunotherapy: the evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous immunotherapy and sublingual forms of immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis/conjunctivitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024; 12: 1415-1427.

35. Zemelka-Wiacek M, Agache I, Akdis CA, et al. Hot topics in allergen immunotherapy, 2023: current status and future perspective. Allergy 2024; 79: 823-842.

36. Zhang J, Yang X, Chen G, et al. Efficacy and safety of intratonsillar immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2024; 132: 346-354.

37. Contoli M, Porsbjerg C, Buchs S, Larsen JR, Freemantle N, Fritzsching B. Real-world, long-term effectiveness of allergy immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis: subgroup analyses of the REACT study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023; 152: 445-452.

38. Calderón MA, Cox L, Casale TB, Moingeon P, Demoly P. Multiple-allergen and single-allergen immunotherapy strategies in polysensitized patients: looking at the published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 929-934.

39. Nelson HS. Multiallergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 123: 763-769.

40. Liccardi G, Martini M, Bilò MB, et al. Why is pet (cat/dog) allergen immunotherapy (ait) such a controversial topic? Current perspectives and future directions. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2024; 56: 188-191.

41. Virtanen T. Immunotherapy for pet allergies. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018; 14: 807-814.

42. Dávila I, Domínguez-Ortega J, Navarro-Pulido A, et al. Consensus document on dog and cat allergy. Allergy 2018; 73: 1206-1222.

43. Bozek A, Pyrkosz K. Immunotherapy of mold allergy: a review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017; 13: 2397-2401.

44. Coop CA. Immunotherapy for mold allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2014; 47: 289-298.

45. Csonka P, Hamelmann E, Turkalj M, Roberts G, Mack DP. SQ sublingual immunotherapy tablets for children with allergic rhinitis: a review of phase three trials. Acta Paediatr 2024; 113: 1209-1220.

46. Dhami S, Kakourou A, Asamoah F, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2017; 72: 1825-1848.

47. Huang F, Wang DH, Foo CT, Young AC, Fok JS, Thien F. The Melbourne epidemic thunderstorm asthma event 2016: a 5-year longitudinal study. Asia Pac Allergy 2022; 12: e38.

48. O’Hehir RE, Varese NP, Deckert K, et al. Epidemic thunderstorm asthma protection with five-grass pollen tablet sublingual immunotherapy: a clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: 126-128.

49. Farraia M, Paciência I, Castro Mendes F, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for asthma prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized controlled studies. Allergy 2022; 77: 1719-1735.

50. Kristiansen M, Dhami S, Netuveli G, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for the prevention of allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017; 28: 18-29.

51. Penagos M, Durham SR. Allergen immunotherapy for long-term tolerance and prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 149: 802-811.

52. Arshad H, Lack G, Durham SR, Penagos M, Larenas-Linnemann D, Halken S. Prevention is better than cure: impact of allergen immunotherapy on the progression of airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024; 12: 45-56.

53. Valovirta E, Petersen TH, Piotrowska T; GAP investigators. Results from the 5-year SQ grass sublingual immunotherapy tablet asthma prevention (GAP) trial in children with grass pollen allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 529-538.

54. Hamelmann E, Hammerby E, Scharling KS, Pedersen M, Okkels A, Schmitt J. Quantifying the benefits of early sublingual allergen immunotherapy tablet initiation in children. Allergy 2024; 79: 1018-1027.

55. Alviani C, Roberts G, Mitchell F, et al. Primary prevention of asthma in high-risk children using HDM SLIT; assessment at age 6 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145: 1711-1713.

56. Larenas-Linnemann D. Long-term adherence strategies for allergen immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Proc 2022; 43: 299-304.

57. Beutner C, Schmitt J, Worm M, Wagenmann M, Albus C, Buhl T. Lack of harmonized adherence criteria in allergen immunotherapy prevents comparison of dosing and application strategies: a scoping review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023; 11: 439-448.

58. Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis (WUSTL). Clinical outcomes research: sino-nasal outcome tests (SNOT). St Louis, MO: WUSTL; 2024. Available online at: https://otolaryngologyoutcomesresearch.wustl.edu/research/clinical-research/sinusitus/sino-nasal-outcome-tests-snot/ (accessed August 2024).

59. Fonseca JA, Nogueira-Silva L, Morais-Almeida M, et al. Control of allergic rhinitis and asthma test (CARAT) can be used to assess individual patients over time. Clin Transl Allergy 2012; 2: 16.

60. Durham SR, Penagos M. Sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137: 339-349.

61. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Aeroallergen immunotherapy. A guide for clinical immunology/allergy specialists. Sydney: ASCIA; 2022. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/ascia-aeroallergen-immunology-guide (accessed August 2024).

62. ASCIA. Immunotherapy e-training for health professionals. Sydney: ASCIA; 2021. Available online at: https://etraininghp.ascia.org.au (accessed August 2024).