Vaping and the government’s new approach: what GPs need to know

Policy changes were made in May 2023 by the Federal Minister for Health to address the growing use of electronic cigarettes (ECs) and their associated harms. These changes pose some novel challenges for GPs in terms of fully understanding nicotine addiction and addressing this when associated with EC use, as well as managing the limited role for ECs in assisted smoking cessation. GPs play an essential role in addressing this public health issue and reducing the harms associated with smoking and vaping.

- Disposable electronic cigarettes (ECs) have swiftly gained popularity in Australia, resembling historical patterns of the development of cigarette smoking addiction.

- Policy changes were announced in May 2023 to tackle the growing use of ECs, including import restrictions, constraints on flavours and colours, limits on nicotine concentrations and a ban of all single-use disposable vapes.

- GPs are faced with several challenges due to these policy shifts, including the need to refresh their knowledge about nicotine addiction, when to recommend ECs in a limited role for assisted smoking cessation and how to best manage continued nicotine addiction post-vaping cessation.

- The recent legal changes allow more GPs to prescribe unapproved nicotine vaping products via pharmacies, providing opportunities for personalised support and health risk mitigation.

In May 2023, the Federal Minister for Health announced a number of policy changes to address the current and future harms associated with the burgeoning use of electronic cigarettes (ECs).1 Devices of the highest concern are cheap disposables, the use of which greatly exceeds that of the older tank-style devices.2 These disposables have a very high nicotine content masked under pleasant, fruity flavours. Currently, there are no circumstances under which these nicotine-containing products can be sold legally by tobacconists, vape shops or corner stores. Common observations and substantial seizures by health authorities suggest that this law is being widely flouted.3 The dramatic and highly concerning increase in EC use, initially among adolescents but now permeating into young adults and older age groups,4 coincides with the initial trickle of sales in mid-2020 that is now a flood.

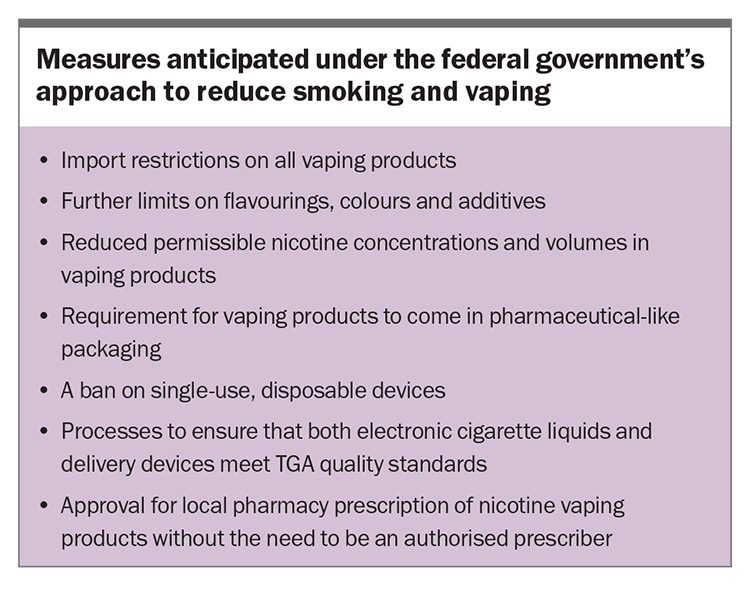

In the proposed model, ECs will continue to be available to assist with smoking cessation within a prescription-based medical access framework. The federal, state and territory governments have all rejected the proposition that ECs should be a freely available consumer product. The measures anticipated under the proposed model are listed in the Box. This article discusses the associated challenges that GPs will need to face, as a result of these policy changes:

- refreshing their understanding of nicotine addiction and the cause of such a large increase in the use of disposable vaping devices

- learning how ECs might effectively and safely be recommended in a limited role for smoking cessation

- addressing the problems of established nicotine addiction related to vaping only, without prior tobacco use, in adolescents and adults

- addressing the problem of continued nicotine addiction subsequent to the use of vaping as a cessation tool in former smokers.

Elements of addiction: why has disposable vape use taken off?

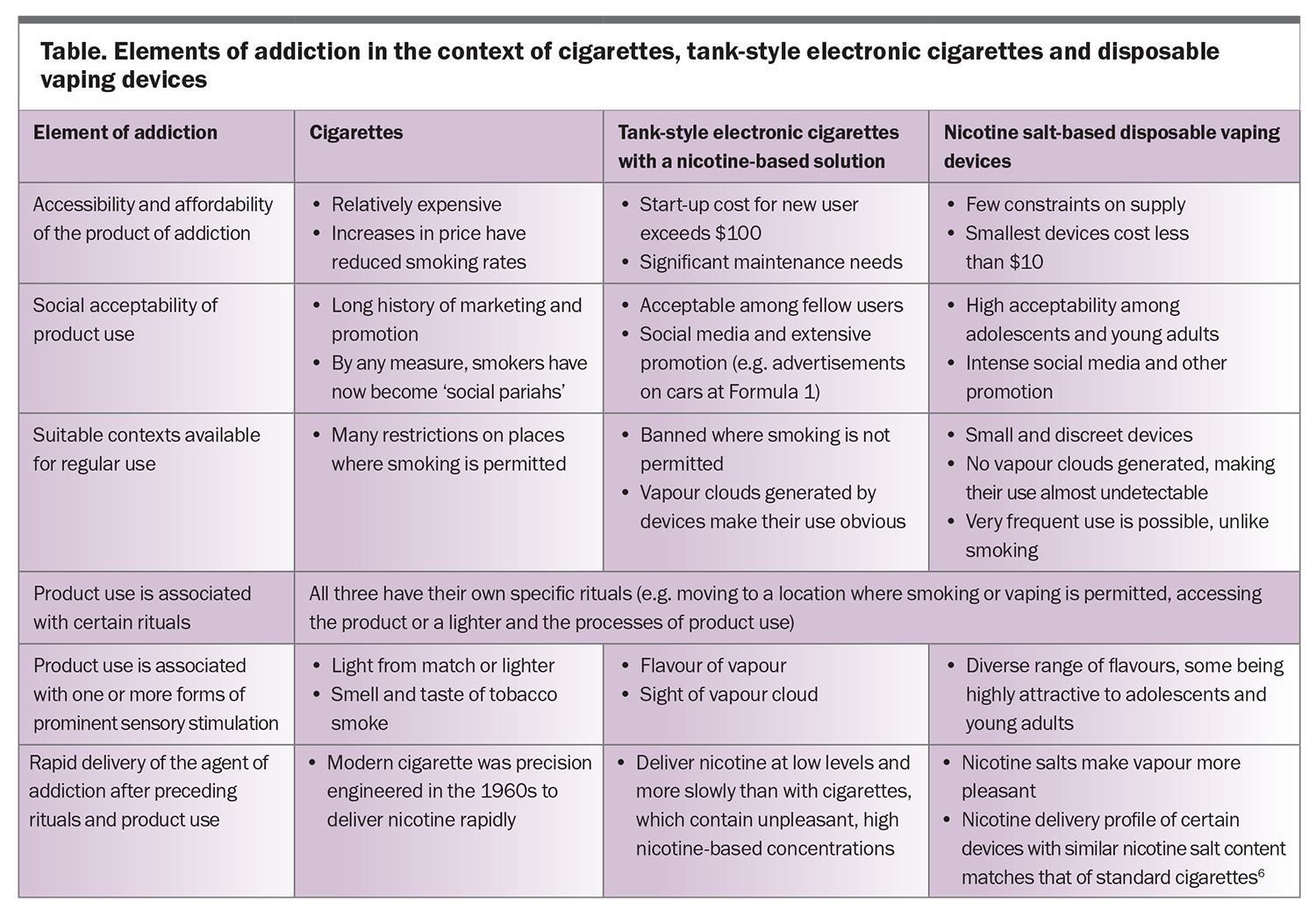

Establishing and maintaining a state of addiction is not simply a matter of intermittent exposure to the agent of addiction. It took 80 years, from 1880 to 1960, for cigarettes to transition from costly hand-rolled products to affordable machine-manufactured products, gain social acceptance and see the tobacco additives necessary to maximise their addictive potential defined.5 In contrast, high-concentration, nicotine salt-based disposable ECs appeared essentially ‘from nowhere’ in 2020 with progression to the current widespread use in Australia in just three years. The principles of their development and use replicate exactly those that led to the rise in cigarette smoking. The Table outlines the key elements of addiction in relation to cigarettes, older ECs and disposable vaping devices.6

General practice, electronic cigarettes and smoking cessation

The limited evidence that supports the use of ECs for smoking cessation is derived from randomised controlled trials in smokers who were highly motivated to use ECs and received personalised support for smoking cessation.7 Advice from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) is that ECs may be recommended reasonably for people who remain motivated but have been unsuccessful in achieving smoking cessation with standard approved therapies in combination with behavioural support.8

Since October 2021, it has been legal for consumers to import nicotine vaping products, such as nicotine-containing ECs, nicotine pods and liquid nicotine if they hold a valid prescription, which could be supplied by any medical practitioner.9 Alternatively, local supply through pharmacies was possible for prescriptions issued by authorised prescribers. The use of a third provision – prescription under the Special Access Scheme – has, by all reports, been minimal. Any GP can prescribe ECs, but the reality is that few do. Nationally, there are almost 2000 authorised prescribers, a minority of which are currently practising GPs.10 A lack of knowledge and experience in the area combined with a reluctance to recommend and prescribe an unapproved product are key influences. Into this void have stepped several online prescription platforms that are unlikely to provide the level of personalised support needed for ECs to be an effective smoking cessation tool.

Under the proposed changes, any GP will be able to prescribe an unapproved nicotine vaping product for local supply via a pharmacy. This will provide the necessary opportunity for personalised GP support and opportunistic modification of other identified health risk factors. Many GPs may choose to recommend a pod-style device and achieve familiarity with that device. This is no different from choosing to become familiar with and prescribe one of a range of antihypertensive therapies, for example.

Vaping devices are not without fault, as they shed toxic metals into the vapour.11 However, the many complexities of recommending a tank-style open system, which introduce the risk of poisoning from nicotine liquid and have a range of solutions and device settings, are daunting for most GPs. The maximum nicotine concentration will be set by regulation at 20 mg/mL, which is the same limit as that in the European Union and UK. Claims that higher-concentration nicotine solutions are needed for smokers who present with stronger features of nicotine dependence lack a strong evidence base.

General practice, nicotine addiction and vaping cessation

If the legal and regulatory changes are effective as planned, most established EC users will no longer have access to an ongoing supply. Some commentators claim that this will create a nicotine withdrawal crisis; however, this seems overblown. It is true that vaping, like smoking, is highly addictive. However, as is the case with smoking, most EC users cease vaping without assistance (‘quit cold turkey’) even if the initial withdrawal symptoms are discomforting.12 It may take several attempts before cessation is established but they do achieve success, as is the case with smoking. There will be adequate warning, before regulatory changes are in place, to allow most EC users to pre-plan and achieve vaping cessation. Quitline has developed a support response (https://www.quit.org.au/).

At this stage, based on the current limited evidence, it remains reasonable to manage nicotine addiction from vaping and smoking in similar fashion. In adults, approved nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) with personalised support is very reasonable. There is more complexity when a parent or carer presents with an adolescent in this clinical situation. A decision to consent to or recommend NRT can be based on a global assessment and consideration of the alternatives. GP-guided NRT with personalised support is very likely to be superior, in terms of efficacy and safety, to unsupported use after over-the-counter purchase. GPs will need to be aware about the features of anxiety and depression, either pre-existent or emerging after cessation.

The RACGP does not recommend the long-term use of ECs after smoking cessation because of their unproven benefits and known harms. Long-term use also does not prevent relapse to smoking.13 In the Australian context, smokers who have switched to vaping with disposables may have increased their nicotine exposure because of the high nicotine delivery from these devices and more liberal opportunities to vape rather than smoke. Such users need effective support as they transition towards proven safe NRTs and, eventually, to complete cessation of nicotine exposure.

Conclusion

Smoking and vaping cessation is a challenging area, with GPs needing to familiarise themselves with the prescription of products that are unapproved and hazardous to health in many circumstances. Nonetheless, it is essential that GPs, as a collective, embrace this role to play their part in addressing this important public health need in the face of increasing EC use. The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network has an excellent guidance document relevant to vaping and EC use in adolescents and young adults.14 It is expected that the RACGP and other learned bodies will provide additional advice to GPs and other medical practitioners to guide them through a range of clinical scenarios in the future. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Peters has served in an honorary role on committees for the National Health and Medical Research Council, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, and NSW Health.

References

1. Butler M (The Hon). Taking action on smoking and vaping. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-mark-butler-mp/media/taking-action-on-smoking-and-vaping (accessed Aug 2023).

2. Watts C, Egger S, Dessaix A, et al. Vaping product access and use among 14-17-year-olds in New South Wales: a cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 814-820.

3. NSW Health. NSW Health seizes more than $1 million of illegal nicotine vapes. St Leonards: NSW Ministry of Health; 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/Pages/20220516_00.aspx (accessed Aug 2023).

4. Wakefield M, Haynes A, Tabbakh T, Scollo M, Durkin S; Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer; Cancer Council Victoria. Current vaping and current smoking in the Australian population aged 14+ years: February 2018-March 2023. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/current-vaping-and-smoking-in-the-australian-population-aged-14-years-or-older-february-2018-to-march-2023?language=en (accessed Aug 2023).

5. Stevenson T, Proctor RN. The secret and soul of Marlboro: Phillip Morris and the origins, spread, and denial of nicotine freebasing. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 1184-1194.

6. Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control 2022; 31: e88-e93.

7. Banks E, Yazidjoglou A, Brown S, et al. Electronic cigarettes and health outcomes: umbrella and systematic review of the global evidence. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 267-275.

8. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. Melbourne: RACGP; 2021. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/supporting-smoking-cessation/recommendations (accessed Aug 2023).

9. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Nicotine vaping products hub. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care: 2023. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved-therapeutic-goods/nicotine-vaping-products-hub (accessed Aug 2023).

10. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Authorised Prescribers of unapproved nicotine vaping products. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care: 2023. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/resource/guidance/authorised-prescribers-unapproved-nicotine-vaping-products (accessed Aug 2023).

11. Block AC, Schneller LM, Leigh NJ, Heo J, Goniewicz ML, O’Connor RJ. Heavy metals in ENDS: a comparison of open versus closed systems purchased from the USA, England, Canada and Australia. Tob Control 12 July 2023; e-pub (https://doi.org/10.1136/tc-2023-057932).

12. Jones E, Endrighi R, Weinstein D, Jankowski A, Quintiliani LM, Borrelli B. Methods used to quit vaping among adolescents and associations with perceived risk, addiction, and socio-economic status. Addict Behav 2023; 147: 107835.

13. Chen R, Pierce JP, Leas EC, et al. Effectiveness of e-cigarettes as aids for smoking cessation: evidence from the PATH Study cohort, 2017–2019. Tob Control 2023; 32: e145-e152.

14. Wahhab M, Milne B. Clinician’s Guide to Supporting Adolescents and Young Adults Quit Vapes 2023. Sydney: The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network; 2023. Available online at: https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/files/attachments/clinicians_guide_to_supporting_aya_quit_vapes_final71.pdf (accessed Aug 2023).