Disordered breathing: assessing and managing the misbehaving larynx

Disorders of the airways often have overlapping and heterogeneous symptoms. Differentiating inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) from laryngeal and respiratory diseases and other functional disorders is key to diagnosis and subsequent therapy. A tailored approach to treatment that takes into account the patient’s specific maladaptive laryngeal breathing postures, known triggers and overall ILO profile and includes input from a multidisciplinary team can help optimise patient management.

- Inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) is a functional disorder of breathing caused by transient, reversible narrowing of the laryngeal airway.

- Other causes of breathlessness and breathing discomfort should be identified or excluded before a diagnosis of ILO is made.

- The clinical features of ILO typically include acute dyspnoea with primary inspiratory or expiratory phase effort and audible noise localised to the larynx.

- Episodes are commonly triggered by internal or external factors, such as reflux, seasonal allergens, cold air, inhaled irritants, exercise and emotional distress.

- Laryngeal-based respiratory retraining therapy with a speech pathologist is typically the first-line approach to treatment after relevant comorbidities have been optimally managed by other specialists within the treating team.

- The diagnosis and treatment of ILO requires a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach between primary care physicians, speech pathologists, respiratory physicians and ENT specialists to enable best outcomes.

The vocal folds play an important role in airway management. They provide protective activity in the pharyngeal phase of swallow secretion management, have a pivotal role in phonation and cough and control airway diameter for the biological purposes of ventilation and gas exchange. Most of these activities are reflexive or not undertaken purposefully; however, these vocal fold movements can be controlled or altered to over-ride automated laryngeal postures to either improve functional efficiency or disrupt normal function. One example of when these movements ‘misbehave’ is coined vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) – a somewhat ubiquitous term that covers a range of possible aberrant vocal fold ‘behaviours’, but most commonly refers to inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) or, historically, paradoxical vocal fold movement disorder.

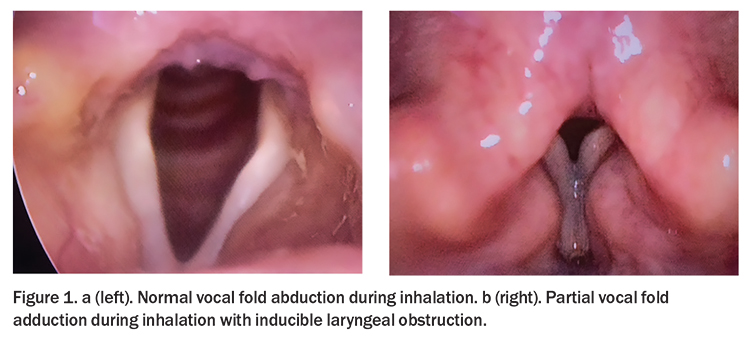

ILO and VCD are disorders of the middle airway and fall under the umbrella term of functional obstructive airway disorders due to their clinical profile. Technically, ILO includes the subtype VCD relating to impedance at the vocal fold level but it can also refer to obstruction of the airway caused by the supraglottic structures. For the purposes of this article, ILO is considered synonymous with VCD and involves involuntary adduction of the vocal fold with or without supraglottic involvement during inspiration (and sometimes expiration) leading to restriction of the airway and breathlessness (Figure 1).1,2 As such, we will refer only to ILO throughout the rest of the article.

Clinical presentation

The functional airway obstruction that occurs in ILO is inappropriate, transient and reversible. Episodes can be frequent or infrequent, fleeting or sustained, obviously related to external or internal triggers or seemingly random. Acute dyspnoea, with inspiratoryphase effort and an audible inhalatory noise, or even stridor, are frequently reported in classic cases of ILO. Patients may also present with regularly effortful breathing, on both inspiratory and expiratory phases. They may experience breathlessness at rest or worsening of symptoms during exertional tasks or in response to common airway triggers, such as cold air, perfumes, inhaled irritants and seasonal allergens. For those with symptoms triggered only by exercise, the condition is known as exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO).

During an ILO episode, patients typically self-report difficulty during the inspiratory phase of the respiratory cycle and often describe a feeling of constriction in the throat or upper chest. Audible inspiratory noise may be heard at rest or on exertion and can be isolated to the larynx. Many patients may also present with audible inhalation or breathlessness during prolonged talking. Subconscious breath-holding behaviours, including adduction of the vocal cords, at times of concentration are also common.

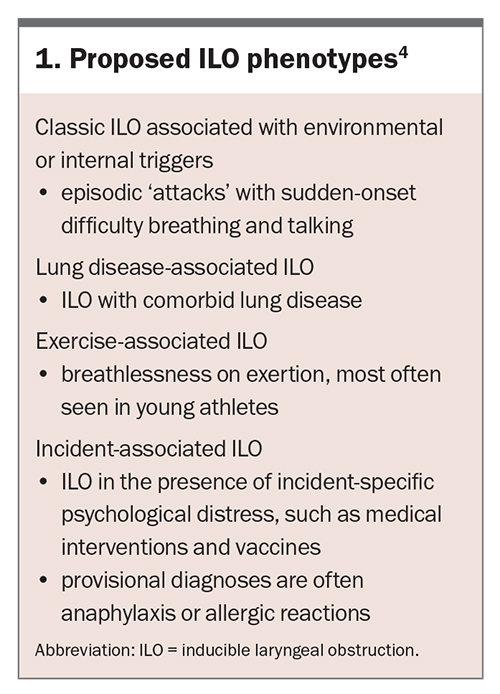

ILO has been reported to be more common among women than men, and among adolescents and adults compared with younger children, but the exact prevalence and incidence is largely unknown.3 Further, although the condition is considerably heterogeneous in aetiology, triggers and presentation, specific phenotypes have been proposed, which may prove useful in delineating triggers and determining the best treatment options (Box 1).4,5

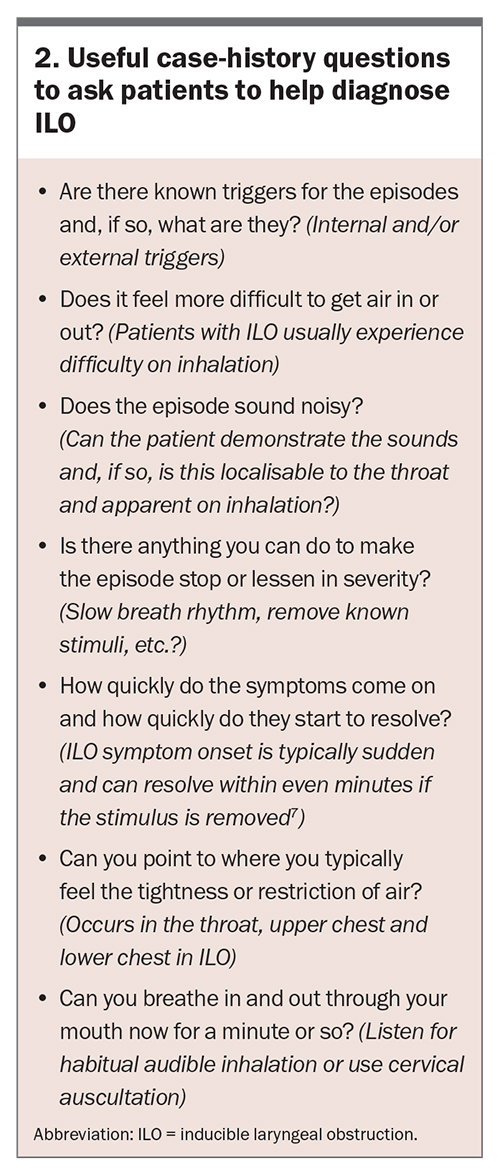

The severity of physical aspects of the condition is based on the frequency and duration of events and the extent of airway obstruction. The overall impact of ILO on the person’s quality of life is typically considerable; however, it is predicated on a myriad of other additional factors, including the often-cascading healthcare interventions that proceed an episode and the patient’s psychosocial reactions and pertinent activity and participation needs. Clinical evaluation and patient-reported outcomes are crucial to the assessment process, and together provide a more thorough understanding of the individual’s airway, ILO triggers and responses. Useful questions to ask to elicit patient observations when taking a clinical history are presented in Box 2. As ILO is essentially a functional disorder, the patient’s individual experience best describes the airway picture, therefore a thorough case-history is important for determining a referral pathway and optimal intervention.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to distinguish functional laryngeal obstruction from other laryngeal disorders, including those due to neurological impairment (e.g. vocal fold paralysis/paresis, dystonias, laryngeal hypersensitivity and multiple systems atrophy), those resulting from structural airway narrowing due to stenosis, or from other respiratory conditions. The clinical manifestations of ILO can develop as a coincidental primary or subsequential secondary effect of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), excessive dynamic airways collapse (EDAC) or other dysfunctional breathing conditions, and these are therefore important to consider as differentials or contributors in cases of unexplained breathlessness.6,7 Pulmonary function testing can help differentiate clinical manifestations and common triggers that induce ILO from those of asthma. Current evidence suggests that up to 50% of patients with asthma and 31% with COPD experience laryngeal obstruction.8

Assessment

ILO is best diagnosed after a thorough respiratory, laryngeal and cardiac evaluation to rule out underlying disease as the cause of breathlessness. It should also remain a differential diagnosis in cases where treatments for underlying disease have not led to resolution or expected improvement of symptoms. Diagnosing ILO can be difficult and is typically the remit of respiratory or ENT specialists. ILO may be strongly suspected after a process of elimination or retrospective careful evaluation of previous event sequences, especially in people with a high degree of responsiveness to corrective laryngeal postures and those who had rapid spontaneous recovery. Flexible nasendoscopy of the upper and middle airway with provocation testing and/or patient recreation of breathlessness or dysfunctional episodes to visualise the function of the airway during an ILO episode is the usual definitive diagnostic assessment; however, this assessment is observational and inadequate in isolation for fully profiling the nature of the ILO. Other investigations, such as flow–volume measurement with spirometry, are important in the work-up and must be further augmented with a rigorous clinical history, and review and optimised treatment of relevant comorbidities, such as laryngopharyngeal reflux, sinus disease or dysphonia, to mitigate their potential contribution to ILO. In the case of exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction, continuous laryngoscopy during exercise may improve diagnostic accuracy, although this investigation is limited to specialised centres and not widely accessible.

Established multidisciplinary airways clinics that combine expertise from respiratory and ENT specialties and speech pathologists, have been shown to be invaluable for people with ILO, especially those with complex cases and who are refractory to standard medical management.2,9

Treatment

Based on the premise that ILO is a functional condition, behavioural intervention with laryngeal-based respiratory retraining therapy (LRT) is commonly accepted as the first-line treatment. Referrals to a speech pathologist for LRT are typically made by respiratory physicians, ENT specialists, allergists, sports medicine physicians and paediatricians only after other medical diagnoses have been excluded or their contribution to the condition identified and management optimised. In our experience, it is not uncommon for patients to then be provisionally diagnosed and referred for LRT on strong clinical grounds, even if there is not confirmatory instrumental evidence of ILO.

Because of the heterogeneity of ILO clinical presentations, LRT needs to be tailored to the individual according to their specific maladaptive laryngeal breathing postures, known triggers and overall ILO profile.10,11 Thus, the exact nature of the program varies between patients in content, intensity, duration and service delivery models. However, therapy sessions typically entail:

- conscious awareness of vocal fold abduction during inhalation and subglottic control of airflow with active recruitment of respiratory muscles

- use of strategies to achieve adequate glottic aperture, enhance laminar airflow and minimise laryngeal interference during respiration, as opposed to ‘throat’ breathing

- respiratory rhythm repatterning

- challenge with or desensitisation to triggers

- emotional and informational counselling.

Treatment invariably involves intensive evaluation and identification of breathing patterns to build the patient’s awareness of their anatomy and teach them how to consciously control elements of the respiratory phases, including abduction (and to a lesser extent adduction) of the vocal cords. Understanding the movement patterns of the vocal cords in different contexts is also important for interoception to establish a firm association between the physiological activity and the individual’s sensation. This may be done through exploring the position and sensations of the larynx, especially the vocal folds, and associated laminar airflow interruptions during phonation, coughing, laughing, whistling and other activities that may elicit vocal fold adduction or a narrowed glottis.

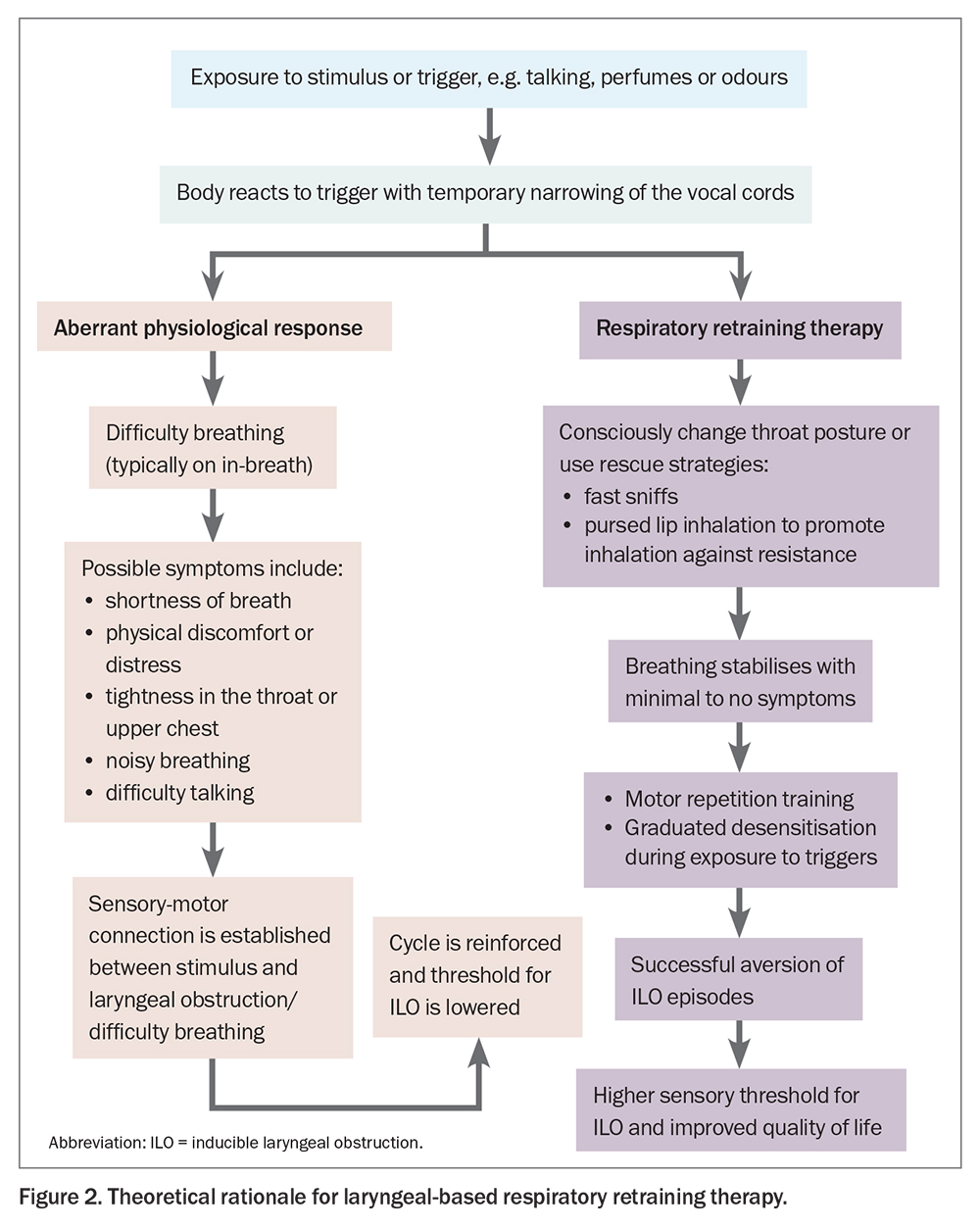

Inspiratory exercises are typically implemented to abduct the vocal cords and maximise the airway diameter during the respiratory cycle. These may include forceful inhalations using sniffing, slow inhalation through the nose, pursed lip or high tongue inhalation postures to promote abduction and reduce or eliminate middle airway constriction and greatly improve breathing comfort. Patients may use these exercises as ‘rescue strategies’ to consciously over-ride the paradoxical movements of the vocal cords during an acute ILO episode. Once competence, confidence and success are achieved, these exercises may then be graduated into desensitisation or challenge activities to consciously reduce laryngeal hyper-responsiveness to previously provocative stimuli or exercise. A theoretical rationale for laryngeal respiratory retraining therapy is presented in Figure 2.

Although LRT is the accepted primary treatment choice, evidence for the value of speech pathology intervention; relies mostly on clinical and observational case series’ or quasi-experimental studies, with variable success rates depending on the patient cohort and outcome measures studied.12 Findings from our retrospective audit of 193 patients with ILO who were seen for speech pathology LRT showed over 80% had at least mild to moderate benefit, of which 38% had resolution of symptoms by the end of therapy, as measured by improvement in frequency and severity of episodes and self-reported ILO-related quality of life.13 An earlier study similarly reported that LRT was successful in 18 of 39 patients (46%) with ILO who attended at least one speech pathology session and 18 of 24 patients (75%) who attended a minimum of four sessions, as measured by a reduction in healthcare utilisation.9

Other interventions that have been proposed for ILO, but usually only sought if LRT is unsuccessful, include medication to reduce laryngeal hypersensitivity (e.g. neuromodulators), laryngeal botulinum toxin or surgical options such as laryngeal keels or supraglottoplasty, but treatment typically relies on clinical judgment on a case-by-case basis.14

Conclusion

ILO is a complex condition with varied clinical manifestations that can considerably compromise quality of life. It is commonly mistaken for asthma or other medical conditions, resulting in long delays in diagnosis and, therefore, appropriate management. Speech pathology intervention is considered the first-line treatment after thorough medical assessment and optimal treatment of comorbidities and common triggers, such as reflux, allergy and sinonasal symptoms. However, significant questions remain regarding aetiological factors and the relevance of phenotypes, triggers and comorbidities to the efficacy of speech pathology or other intervention in reducing symptoms of ILO. Continued, widespread and systematic collection of patient data is recommended to further outline predictors of LRT success that may inform and improve clinical care for this heterogeneous condition. Input from a multidisciplinary team and a multifaceted approach to assessment, determination of best management options, condition surveillance and measurement of treatment outcomes are important to improving patient outcomes. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Haines J, Hull J, Fowler SJ. Clinical presentation, assessment, and management of inducible laryngeal obstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018; 26: 174-179.

2. Halvorsen T, Walsted ES, Bucca C, et al. Inducible laryngeal obstruction: an official joint European Respiratory Society and European Laryngological Society statement. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1602221.

3. Malaty J, Wu V. Vocal cord dysfunction: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician 2021; 104: 471-475.

4. Leong P, Phyland DJ, Koh J, Baxter M, Bardin PG. Middle airway obstruction: phenotyping vocal cord dysfunction or inducible laryngeal obstructions. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 1: 3-5.

5. Guglani L, Atkinson S, Hosanagar A, Guglani L. A systematic review of psychological interventions for adult and pediatric patients with vocal cord dysfunction. Front Pediatr 2014; 2: 82.

6. Gauthier MC, Fajt ML. Is it asthma? Recognizing asthma mimics. In: Difficult to treat asthma: clinical essentials. Eds Khurana S, Holguin F. Humana Cham; 2020. p. 25-38.

7. Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Loukou I, Douros K. Differentiating vocal cord dysfunction from asthma. J Asthma Allergy 2017; 10: 277-283.

8. Dunn NM, Katial RK, Hoyte FC. Vocal cord dysfunction: a review. Asthma Res Pract 2015; 1: 1-8.

9. Baxter M, Ruane L, Phyland D, et al. Multidisciplinary team clinic for vocal cord dysfunction directs therapy and significantly reduces healthcare utilization. Respirology 2019; 24: 758-764.

10. Sandage MJ, Milstein CF, Nauman E. Inducible laryngeal obstruction differential diagnosis in adolescents and adults: a tutorial. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2023; 32: 1-17.

11. Johnston KL, Bradford H, Hodges H, Moore CM, Nauman E, Olin JT. The Olin EILOBI breathing techniques: description and initial case series of novel respiratory retraining strategies for athletes with exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction. J Voice 2018; 32: 698-704.

12. Mahoney J, Hew M, Vertigan A, Oates J. Treatment effectiveness for vocal cord dysfunction in adults and adolescents: a systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy 2022; 53: 387-404.

13. Phyland D, Brear M. Speech pathology and vocal cord dysfunction/inducible laryngeal obstruction - clinical perspectives on easing the flow. Research paper presented at the Voice Foundation, Philadelphia, USA 2022. [preparing for publication]

14. Haines J, Slinger C, Smith JA, Selby J. Laryngeal considerations in complex breathlessness. In: Hull JH, Haines J, eds. Complex breathlessness (ERS Monograph). Sheffield: European Respiratory Society; 2002. p. 75-91.