Vocal cord dysfunction: the great mimicker of asthma

Vocal cord dysfunction is an under-recognised condition. Its presentation often mimics asthma or severe upper airway obstruction. It is important for primary care providers who are likely to care for patients with a history of recurrent dyspnoea or wheeze to be aware of this condition.

- Symptoms of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) such as sudden episodic breathlessness, wheeze and stridor can often mimic asthma.

- Misdiagnosis of VCD is associated with high healthcare use, inappropriate therapeutic management and subsequent morbidity.

- VCD should be suspected in patients with clinical features suggestive of asthma whose symptoms are not abated with usual asthma therapy.

- In patients suspected of having VCD, spirometry with flow-volume curves during the symptomatic period can aid diagnosis. Variable flattening of the inspiratory curve indicates VCD.

- The gold standard for diagnosis of VCD requires direct visualisation of the paradoxical vocal cord movement during the symptomatic period using flexible laryngoscopy.

- The mainstays of treatment for VCD are behavioural and speech therapy, as well as management of known precipitating factors.

Picture credit: © Top image: Poprotskiy Alexey/Shutterstock.com insets: Chris Wikoff, 2017

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) is a condition that has been described as far back as the 19th century, although it has been published in the literature under a myriad of other names, including Munchausen’s stridor, emotional laryngeal wheezing, factitious asthma or paradoxical vocal cord motion.1-5 Patients with this condition are often misdiagnosed, frequently present to emergency departments and are high users of other healthcare services. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to diagnose VCD. The aim of this article is to raise awareness of this condition within the medical community and to discuss its clinical features, relevant investigations and management.

What is VCD?

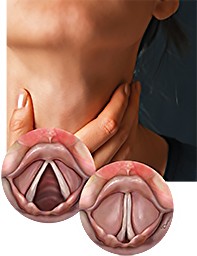

In normal respiration, the vocal cords should be open (abducted). With inspiration they abduct further, thereby increasing the cross-sectional area between the vocal cords. The reverse happens during expiration, when the vocal cords partially close (adduct) by up to 30%. VCD describes the paroxysms of inappropriate and unintentional vocal cord adduction during breathing. These episodes of paradoxical vocal cord movements are more commonly seen during inspiration, although they can occur during both stages of the breathing cycle. In VCD, the inappropriate adduction of the vocal cords leads to narrowing of the airway opening, which can manifest as episodic dyspnoea, wheezing and stridor (Figure 1).

Epidemiology

Given the lack of uniformity in terminology and diagnostic criteria and the under-recognition of VCD, the incidence of this condition is unknown. Estimated prevalences of VCD have ranged from 2.5% of patients presenting to an asthma clinic to 22% of patients with recurrent presentations for breathlessness to an emergency department.6,7 Historically, VCD was predominantly reported in abused women and in female healthcare workers.8,9 Most of the literature continues to suggest that VCD has a female preponderance (of about 2:1).10,11 It is now also recognised that elite athletes, some military personnel and people with high levels of exposure to irritants are more at risk of developing this condition.12 VCD has been reported in both adults and children.

What causes VCD?

The exact pathophysiology of VCD is unclear, and although this condition was once thought to be psychogenic it is now accepted that it is likely to represent a functional disorder that may relate to the complex role of the larynx, which includes breathing, phonating, swallowing, coughing and vomiting, and to the role of the glottis in protecting the trachea and the lungs.7 Autonomic imbalance, laryngeal sensory neuropathy and laryngeal hyper-responsiveness have been postulated as possible mechanisms for VCD.13

Although the pathophysiology of VCD remains uncertain, precipitating factors such as exercise, airborne irritants, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, postnasal drip, emotional stressors and psychiatric conditions have all been reported to be known triggers for VCD. Some patients have also been reported to show priming effects, whereby their trigger for VCD can move from only one factor to multiple factors over time.14

The relationship between VCD and asthma is unclear given the lack of prospective evaluation, and differentiating between the two conditions can be difficult. VCD and asthma are known to coexist. One study has shown that 53 of 95 patients fulfilling laryngoscopic criteria for VCD also had coexistent asthma.9 It can be difficult to discern whether patients with VCD have underlying reactive airways disease, or whether underlying asthma is a trigger for VCD. Further difficulty arises because patients with VCD can show a positive response to a methacholine challenge test, so this test should not be used for distinguishing VCD from asthma.

Clinical features of VCD

Many of the symptoms that patients with VCD report are nonspecific and can therefore mimic other conditions. Given the multitude of possible triggers, it is not uncommon for VCD symptoms to vary in timing and intensity. Patients might be completely asymptomatic in between episodes. Obtaining a clinical history focused on the relevant features of VCD may be helpful (Box 1).14

Patients with VCD generally report sudden onset-dyspnoea, throat tightness, wheezing, stridor, air hunger and dry cough. The sensation of dyspnoea is mostly related to breathing in rather than breathing out (in contrast to asthma), and the sensation of constriction is mostly felt over the neck. Some patients also report globus sensation. The symptoms can sometimes be felt to be life-threatening and it is common for patients to present in a panic. A sensation of light-headedness is not uncommon and is related to hyperventilation.15 Occasionally, patients can be left with dysphonia after the episode.

Physical examination during the symptomatic period generally reveals stridor and/or wheezing, and the degree of respiratory distress may vary from minimal to severe. Stridor can be heard during inspiration, expiration or both. It is generally loudest over the neck. An episode of VCD may last from minutes to days, in contrast to laryngospasm, which usually subsides over seconds or minutes. In most circumstances, patients will have normal peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2), although the presence of oxygen desaturation does not rule out VCD. Patients with VCD lack a symptomatic response to asthma therapy, and symptoms can sometimes be abated by distractions. During the asymptomatic period, physical examination findings are generally normal.

What mimics VCD?

As VCD symptoms are nonspecific, the differential diagnosis for VCD is wide and can include all conditions that cause obstructive airway symptoms (Box 2). However, this condition is most commonly confused with asthma, as demonstrated by numerous cases in the medical literature. One retrospective review of 42 patients with VCD showed that, on average, these patients had been misdiagnosed for 4.8 years.9 Misdiagnosis of VCD as asthma has been associated with various morbidities including intubation, tracheostomy, prolonged high-dose corticosteroid treatment, recurrent hospital admissions and long-term psychological effects.8,9,16-18 It is therefore of paramount importance that the diagnosis of VCD is considered in patients with unusual clinical features.

Apart from asthma, VCD is also often mistaken for angioedema, anaphylaxis, laryngospasm, or a laryngeal or proximal tracheal mass.

Unlike VCD, angioedema is generally not isolated to the larynx and patients will usually present with oedema of the upper airway and neck.

In patients with anaphylaxis, clinical features suggestive of cardiovascular collapse, such as hypotension, are often present.

Patients with laryngospasm have a sustained, virtually complete closure of the vocal cords, and the episode will almost certainly be associated with significant oxygen desaturation. In contrast, patients with VCD show spasmodic adduction of the vocal cords and a wider range of glottis narrowing. Given that laryngospasm is physiologically related to VCD, some experts argue that laryngospasm is a severe form of VCD.

A patient with a laryngeal or proximal tracheal mass can present with stridor, although the presentation is not usually acute and episodic. This condition is usually associated with progressive voice changes.

How do you diagnose VCD?

Spirometry with flow-volume curves and flexible laryngoscopy are the two most useful investigations for diagnosing VCD. Spirometry performed during the symptomatic period will typically show no airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/ forced vital capacity [FVC] ≥0.70), but there is a variable flattening of the inspiratory curves (Figure 2). This contrasts with spirometry performed during an asthma attack, which will show airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC <0.70) but not flattening of the flow-volume curves on either inspiration or expiration. Using spirometry and carefully examining the flow-volume curves for patients with possible VCD is therefore of benefit and should be considered in the primary care setting. During the asymptomatic period, the flow-volume curves of patients with VCD can appear normal (Figure 3).

As mentioned above, a methacholine challenge test result can be positive in patients with VCD and has been shown to induce acute attacks of symptoms in patients with this condition.19 A recent study showed that the mannitol challenge test can similarly induce paradoxical vocal cord movement in patients with VCD.20 Methacholine challenge testing and other provocative measures (e.g. exercise, irritant exposures) have been used in clinical settings to try to induce the symptoms and trigger VCD during testing; however, a negative response to these provocations does not rule out VCD.

Direct visualisation of the vocal cords via flexible laryngoscopy during the symptomatic period is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of VCD. This will show paradoxical complete adduction of the vocal cords during inspiration and occasionally during expiration (Figure 4). If the patient is asymptomatic at the time of this procedure, incorporation of certain manoeuvres such as panting, deep breathing and phonating can sometimes elicit the symptoms.21,22 A normal finding on flexible laryngoscopy when it is performed during the asymptomatic period does not rule out the diagnosis.

Although a chest x-ray is useful in investigating dyspnoea, this is not a useful investigation for diagnosing VCD or for differentiating VCD from asthma, because it is often normal in both asthma and VCD. A chest x-ray with hyperinflation can be helpful in raising the likelihood of asthma but it does not rule out the presence of VCD. A CT scan of the chest is a useful investigation to rule out other causes of dyspnoea and stridor such as tracheomalacia or tracheal and extratracheal masses. A novel imaging technique using dynamic-volume CT has been used in the research setting to diagnose VCD; however, this technique is not yet standardised or widely adopted.23

How do you manage patients with VCD?

Management of patients with VCD in the acute care setting centres on reassurance and supportive care until the episode resolves. Reassuring the patient that their condition is benign and highlighting that their oxygen saturations are maintained can often be helpful in alleviating the symptoms. Certain breathing techniques such as forced sniffing, panting or pursed-lip breathing can sometimes abort their symptoms. These techniques aim to break the irregular breathing pattern, relax the vocal cords and widen the glottis aperture. Continuous positive airway pressure, sedation and inhalation of a helium–oxygen mixture have also been reported to be useful in the acute setting.7,11

Optimal long-term management of patients with VCD requires a multidisciplinary approach and generally starts with a correct diagnosis followed by education of the patient about the condition. Although there is no high-level evidence to indicate which treatment approach is best, the involvement of multiple healthcare professionals is often required. This will generally include a GP, respiratory physician, ear, nose and throat specialist, psychiatrist and speech pathologist. The mainstays of treatment for patients with VCD are behavioural and speech therapy, in addition to strategies that minimise the precipitating factors.

Speech therapy delivered by a speech pathologist who has an interest in VCD is important. Comprehensive management of the condition includes managing triggers and educating the patient to recognise symptoms and laryngeal-abusive behaviours and employ breathing manoeuvres. Techniques such as throat relaxation with abdominal support, cough suppression, throat-clearing suppression, quick inhalation and pursed-lip breathing have been shown to help control the laryngeal response and abort VCD episodes.12,14

In patients with significant psychological components accounting for VCD symptoms, input from psychologists or psychiatrists is also an important part of management. Psychotherapy has been shown to increase treatment efficacy when added to other therapeutic approaches, and the use of the antidepressant amitriptyline (off-label use) was shown to be effective in reducing VCD symptoms in 90% of 62 patients in a case series.13,24,25

Treatment of other comorbidities such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and postnasal drip are recommended, as these are thought to compound VCD symptoms. An uncontrolled trial among a series of seven patients showed that pretreatment with ipratropium may be beneficial in patients with exercise-induced VCD, although further studies are needed to confirm this.26

Intralaryngeal botulinum toxin injection has been trialled with varying success and is currently an option for those patients with protracted VCD (off-label use) for which other trialled therapeutic options have not been successful.7,14

When should patients be referred?

GPs manage a large population of patients with asthma and it is important that they recognise the possible differentiating features of VCD from asthma (Table) and consider the diagnosis of VCD in patients with certain atypical clinical features (Box 3). Given that VCD is often mistaken for asthma and the diagnosis of VCD can be difficult due to its episodic nature, referring patients to a respiratory physician or ear, nose and throat specialist is recommended when the diagnosis is suspected.

Conclusion

VCD is an under-recognised condition and is a great mimicker of asthma, given its similar clinical symptoms. VCD should be suspected in patients with asthma-like symptoms who do not respond to usual asthma therapy.

Increased awareness and understanding of VCD is imperative to reduce the consequent inappropriate therapeutic management and morbidity associated with misdiagnosis. Management of VCD requires a multidisciplinary approach. Speech and behavioural therapy are the mainstays of treatment, but identifying and treating known triggers are also considered to be important. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

2. Patterson R, Schatz M, Horton M. Munchausen’s stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy 1974; 4: 307-310.

3. Rodenstein DO, Francis C, Stranescu DC. Emotional laryngeal wheezing: a new syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983; 127: 354-356.

4. Downing ET, Braman SS, Fox MJ, Corrao WM. Factitious asthma: physiological approach to diagnosis. JAMA 1982; 248: 2878-2881.

5. Powell DM, Karanfilov BI, Beechler KB, Treole K, Trudeau MD, Forrest LA. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in juveniles. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 126: 29-34.

6. Ciccolella DE, Brennan KJ, Borbely B. Identification of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) and other diagnoses in patients admitted to an inner city university hospital asthma center [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: A82.

7. Kenn K, Balkissoon R. Vocal cord dysfunction: what do we know? Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 194-200.

8. Christopher KL, Wood RP 2nd, Eckert C, Blager FB, Raney RA, Souhrada JF. Vocal cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. N Engl J Med 1983; 308: 1566-1570.

9. Newman KB, Mason UG, Schmaling KB. Clinical features of vocal cord dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152: 1382-1386.

10. Brugman S. The many faces of vocal cord dysfunction: what 36 years of literature tells us [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: A588.

11. Morris MJ, Allan PF, Perkins PJ. Vocal cord dysfunction: aetiologies and treatment. Clin Pulm Med 2006; 13: 73-86.

12. Balkissoon R, Kenn K. Asthma: vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) and other dysfunctional breathing disorders. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 33: 595-605.

13. Idrees M, FitzGerald JM. Vocal cord dysfunction in bronchial asthma. A review article. J Asthma 2015; 52: 327-335.

14. Hoyte FC. Vocal cord dysfunction. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 2013; 33: 1-22.

15. Parker JM, Berg BW. Prevalence of hyperventilation in patients with vocal cord dysfunction. Chest 2002; 122: 185S-186S.

16. Heiser JM, Kahn ML, Schmidt TA. Functional airway obstruction presenting as stridor. A case report and literature review. J Emerg Med 1990; 8: 285-289.

17. Newman KB, Dubester SN. Vocal cord dysfunction. Masquerader of asthma. Sem Resp Crit Care Med 1994; 15: 161-167.

18. Hayes JP, Nolan MT, Brennan N, FitzGerald MX. Three cases of paradoxical vocal cord adduction followed up over 10-year period. Chest 1993; 104: 678-680.

19. Perkins PJ, Morris MJ. Vocal cord dysfunction induced by methacholine challenge testing. Chest 2002; 122: 1988-1993.

20. Tay TR, Hoy R, Richards AL, Paddle P, Hew M. Inhaled mannitol as a laryngeal and bronchial provocation test. J Voice 2017; 31: 247.e19-247.e23.

21. Morris MJ, Christopher KL. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of vocal cord dysfunction. Chest 2010; 138: 1213-1223.

22. Ibrahim WH, Gheriani HA, Almohamed AA, Raza T. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J 2007; 83: 164-172.

23. Holmes PW, Lau KK, Crossett M, et al. Diagnosis of vocal cord dysfunction with high resolution dynamic volume computerized tomography of the larynx. Respirology 2009; 14: 1106-1113.

24. Husein OF, Husein TN, Gardner R, et al. Formal psychological testing in patients with paradoxical vocal fold dysfunction. Laryngoscope 2008; 118: 740-747.

25. Varney V, Parnell H, Evans J, Cooke N, Lloyd J, Bolton J. The successful treatment of vocal cord dysfunction with low dose amitriptyline - including literature review. J Asthma Allergy 2009; 2: 105-110.

26. Doshi DR, Weinberger MM. Long-term outcome of vocal cord dysfunction. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96: 794-799.