The GINA 2023 report. What’s new in asthma management?

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) publishes a global strategy for asthma prevention and management that is updated every year based on a review of new evidence. Key changes in the GINA 2023 strategy report, published in May 2023, include treatment strategies for adults and adolescents to reduce the risk of severe exacerbations and minimise adverse effects, the writing of an asthma action plan for patients on different treatment regimens, and how to reduce the environmental impact of asthma and its treatment.

- The goals of asthma treatment are to relieve and control symptoms, reduce the risk of severe exacerbations and minimise adverse treatment effects, such as from oral corticosteroids and overuse of short-acting beta2-agonists (SABA).

- Adults, adolescents and children aged between 6 and 11 years with asthma should receive inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-containing medication, and should not be treated with SABA alone.

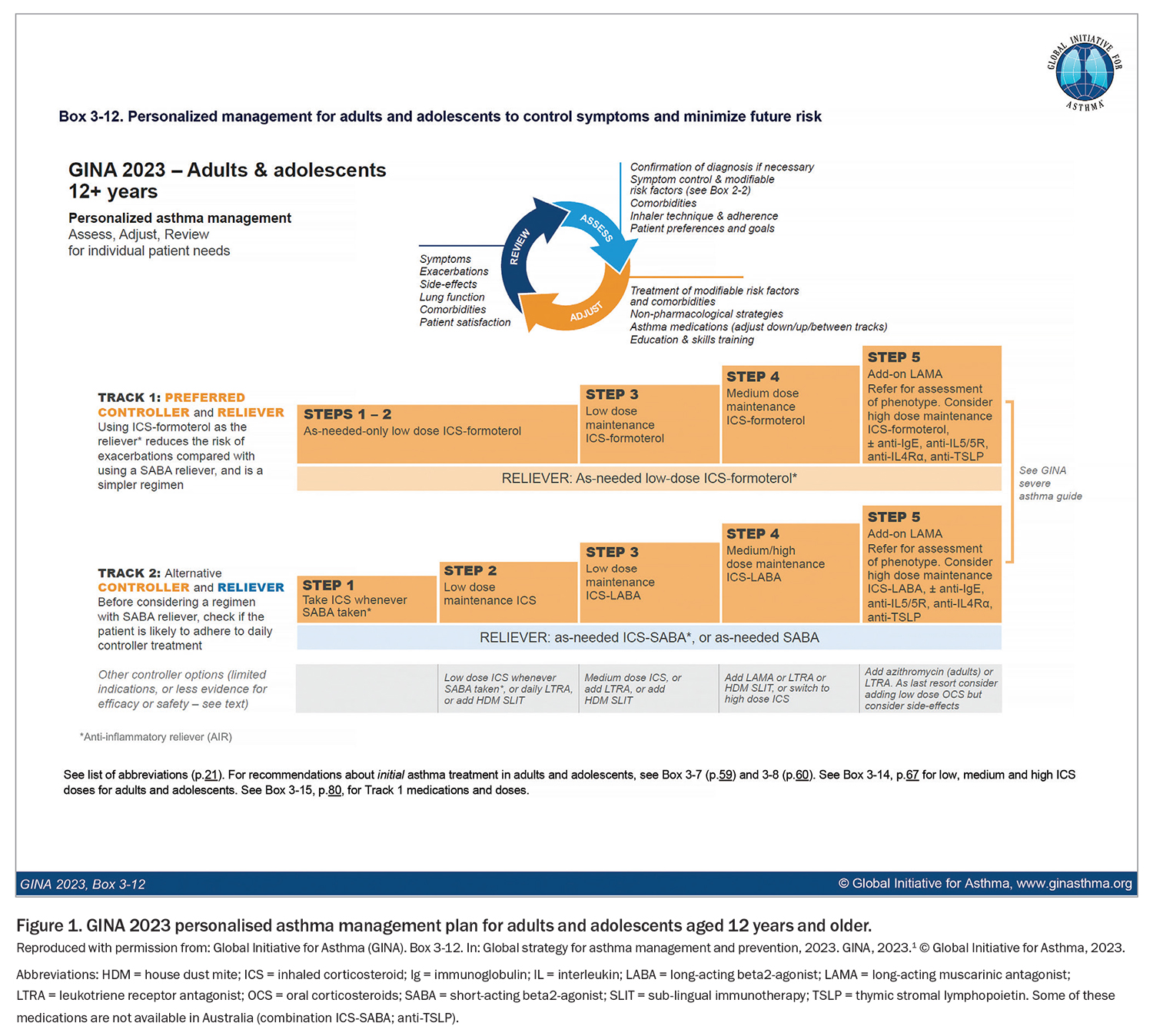

- The 2023 GINA strategy divides treatment for adults and adolescents into two ‘Tracks’ for simplicity: in Track 1, the reliever is as-needed combination low-dose ICS-formoterol; this is the preferred treatment option; Track 2 uses SABA as the reliever along with a separate preventer inhaler, and is an alternative treatment approach.

- Asthma management also includes treating modifiable risk factors and comorbidities, checking and correcting adherence and inhaler technique, nonpharmacological strategies and self-management education.

- All people with asthma should have a written action plan, tailored to each individual’s reliever type, and it should be assessed and updated regularly.

- To mitigate the environmental impact of asthma and its treatment, GINA emphasises the importance of first choosing the right medication for the patient to reduce their risk of severe exacerbations and avoid SABA use (or overuse), then identifying which inhaler(s) they can use correctly as well as their relative environmental impact.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) publishes an annually updated evidence-based strategy for asthma prevention and management.1 This article summarises some of the key changes in the 2023 GINA report, published in May 2023, that are relevant to GPs, specialists and allied healthcare professionals looking after patients with asthma in Australia.

What is GINA?

GINA was established by the WHO and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute 30 years ago, to increase awareness about asthma, and improve asthma prevention and management through a co-ordinated worldwide effort. GINA has been independent since 2014, funded only by the sale and licensing of its reports and figures. GINA publishes an annually-updated global strategy report that can be adapted for local health systems and local medicine availability.1 The GINA Strategy Report is widely used in over 200 countries, with the 2023 report downloaded almost 300,000 times since its publication in May.

The annual GINA updates are based on a twice-yearly cumulative review of new evidence about asthma (original research and systematic reviews). The evidence is not limited to specific questions, but is integrated across the whole asthma strategy. The GINA report has a practical focus, explaining not only ‘what’ the recommendations are, but ‘why’ and ‘how’ they can be implemented. It undergoes extensive external review. The 2023 GINA report, Pocket Guide and slide set can be downloaded from the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org/reports/).1

What are the goals of asthma treatment?

For every patient with asthma, the aims of treatment are to relieve and control symptoms and reduce the risk of severe exacerbations and adverse treatment effects. Tools such as the Asthma Control Test and Asthma Control Questionnaire only assess symptom control; however, patients with mild or infrequent symptoms can still have severe, life-threatening or fatal exacerbations. For example, among patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with acute severe asthma, up to one-third had symptoms less than weekly in the previous three months, and in a study of asthma deaths in young people, 28% previously had sporadic mild symptoms.2,3 These risks can be markedly reduced by inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), leading to the GINA recommendation in 2019 that asthma should no longer be treated with short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) alone.4-8 Instead, all adults, adolescents and children aged between 6 and 11 years with asthma should receive ICS, either regularly or, in adults and adolescents with mild asthma, with as-needed combination ICS-formoterol or by taking ICS whenever SABA is taken. However, in a nationally representative survey, almost 40% of adults in Australia with asthma had taken no ICS in the previous 12 months, leaving them exposed to the risks of SABA-only treatment.9,10 Starting treatment with SABA alone trains the patient to regard it as their primary asthma treatment, so when a preventer inhaler is prescribed, patients are poorly adherent.11,12

The goal of reducing asthma risks also includes reducing the risk of adverse effects of oral corticosteroids (OCS) and of SABA overuse. The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) recently published a position paper highlighting the need for OCS stewardship, with the aim of reducing the use of both frequent short OCS courses and maintenance OCS.13 GINA emphasises that the need for OCS courses can be markedly reduced by optimising inhaled therapy (as below) and treating comorbidities, and, for severe asthma, by using biological therapy based on the patient’s inflammatory phenotype. GINA also recommends that maintenance OCS should be used only as last resort.1 SABA overuse; for example, the dispensing of three or more canisters of salbutamol in a year, is associated with an increased risk of severe exacerbations, and dispensing of one or more canisters a month is associated with an extremely high risk of asthma death.14 In a recent survey, over 50% of patients with asthma in Australia were dispensed three or more canisters of SABA in a year.15

What are the GINA 2023 treatment tracks?

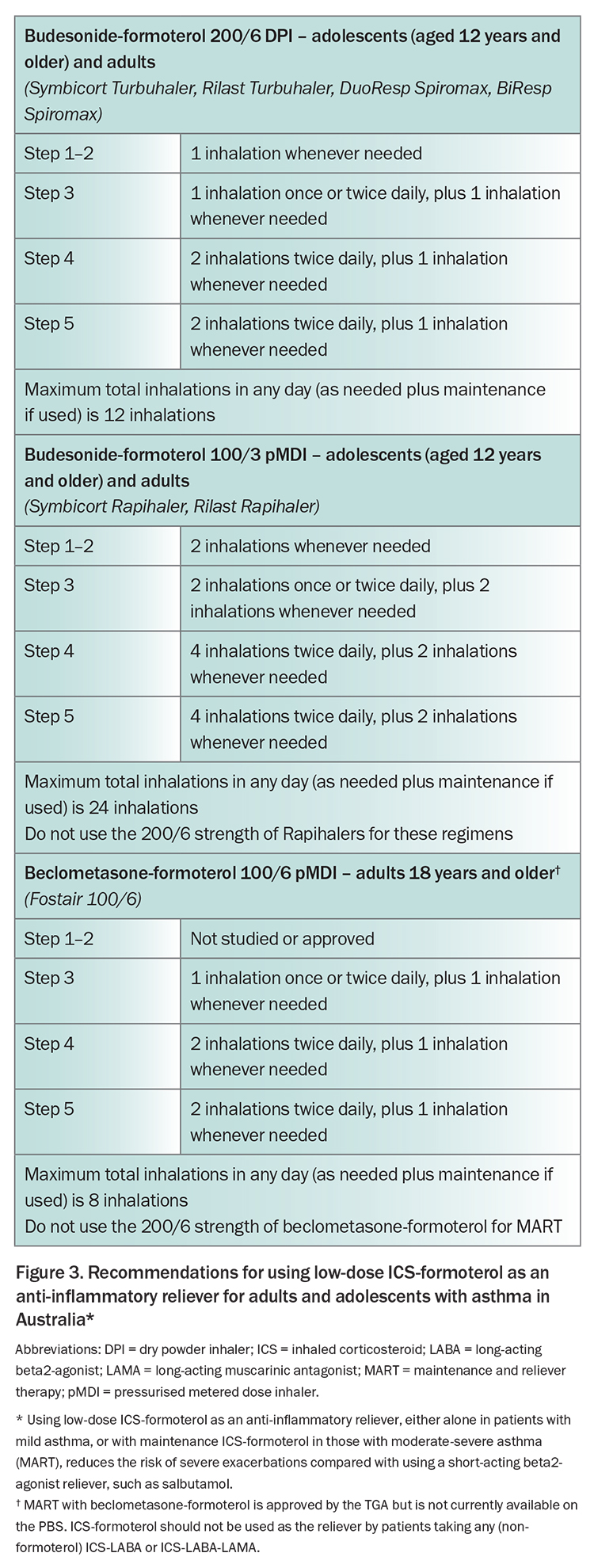

GINA recommendations for asthma treatment in adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older are divided into two ‘tracks’ for simplicity, with the key difference being the type of reliever used (Figure 1). Showing treatment in two tracks makes it easy to see what the treatment options are at each step, and how a patient’s treatment can be stepped up or down according to clinical need.1

Track 1. The patient’s reliever is as-needed combination low-dose ICS-formoterol, which is taken for symptom relief or before exercise or allergen exposure. For most patients, ICS-formoterol relieves symptoms as quickly, or almost as quickly, as a SABA.16 In Steps 1–2 (combined in Track 1), as-needed low-dose ICS-formoterol is the patient’s only asthma treatment.7,17-19 In Steps 3 to 5, the patient also takes ICS-formoterol as their daily maintenance treatment. This is called ‘maintenance and reliever therapy’ (MART).20-22

Track 2. The patient’s reliever is a SABA, such as salbutamol. In Step 1, the patient takes a low-dose ICS whenever they take their SABA for symptom relief; in Step 2, they take daily low-dose ICS; in Step 3, the maintenance treatment is changed to daily low-dose ICS-long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA); and in Steps 4 and 5, the dose of ICS-LABA is increased.

Why is Track 1 with ICS-formoterol reliever the preferred treatment in GINA 2023 for adults and adolescents?

Strong evidence from large clinical trials in over 10,000 patients with mild asthma23 and over 26,000 patients with moderate-severe asthma20,21 shows that using ICS-formoterol as an anti-inflammatory reliever reduces the risk of severe exacerbations compared with conventional treatment plus a SABA reliever, with similar symptom control and a lower dose of ICS. Based on this evidence, GINA recommends Track 1, with ICS-formoterol reliever, as the preferred treatment strategy for adults and adolescents across treatment steps. Track 1 is also preferred because of its simplicity, as patients need only a single medication for both symptom relief and risk reduction.

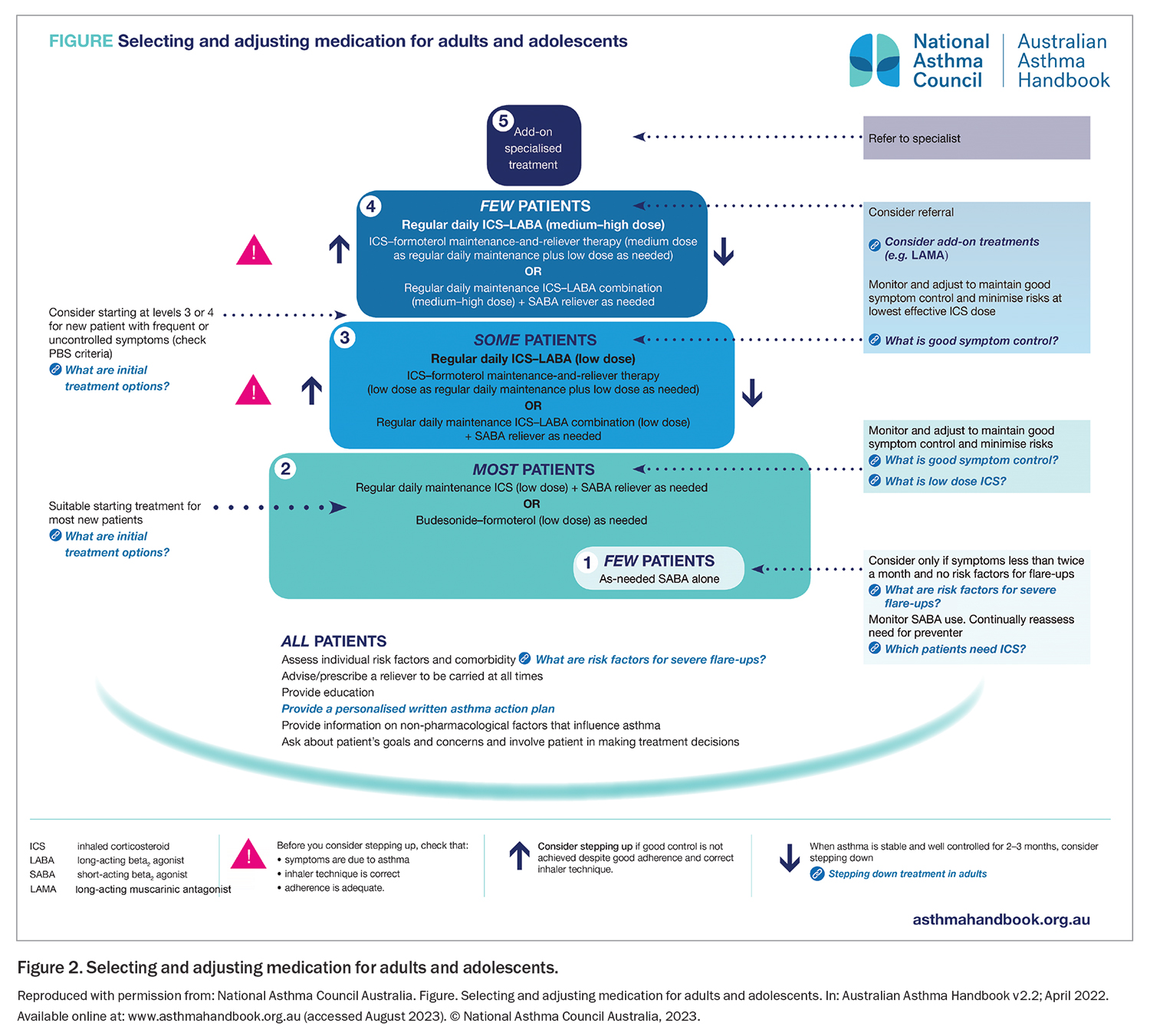

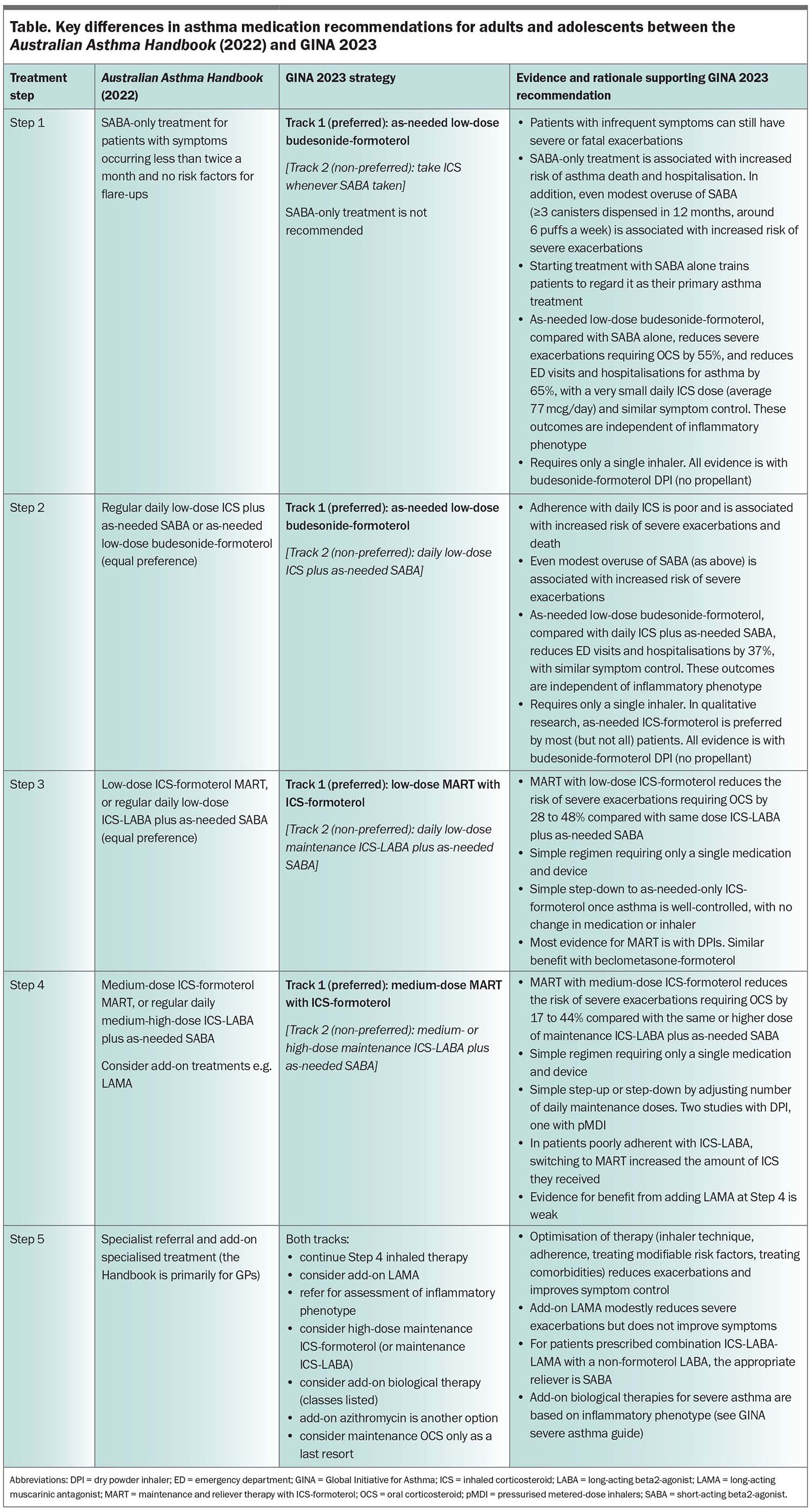

The benefits of GINA Track 1 are particularly substantial in patients with mild asthma, with a 2021 Cochrane meta-analysis finding that as-needed-only low-dose ICS-formoterol reduced the risk of severe exacerbations requiring OCS and asthma-related hospitalisation or ED visits by about two-thirds compared with SABA alone.23 Compared with daily ICS, it reduced the risk of ED visits and hospitalisations by over one-third, without the need for patients taking treatment every day.23 Treatment of mild asthma with as-needed-only budesonide- formoterol is approved by regulators in almost 50 countries, and is recommended in guidelines in 32 countries. MART is approved by regulators in over 120 countries worldwide, based on the reduction in severe exacerbations compared with ICS-LABA plus as-needed SABA.20,21 In Australia, as-needed-only ICS-formoterol is approved by regulators, subsidised on the PBS and has been included in the Australian asthma guidelines (the Australian Asthma Handbook) since 2020. These guidelines give as-needed-only ICS-formoterol equal preference to daily ICS (Figure 2, Table), perhaps because new data since then (including the 2021 Cochrane meta-analysis) have not been reviewed. Similarly, MART has been approved, subsidised and recommended for moderate-severe asthma in Australia since 2007; however, the guidelines (Figure 2, Table) give it equal preference to conventional therapy with ICS-LABA plus as-needed SABA. The above evidence suggests the potential for a large reduction in urgent healthcare utilisation in Australia with use of ICS-formoterol reliever compared with conventional treatment with a SABA reliever.

Track 2 is suggested by GINA as an alternative approach for adults and adolescents when as-needed ICS-formoterol is not available (not the case in Australia) or is not preferred by a patient who has stable asthma and no exacerbations on their current therapy. However, before prescribing asthma treatment with a SABA reliever, it is essential to consider whether the patient will adhere to their ICS-containing therapy, as otherwise they will be exposed to SABA-only treatment and a higher risk of exacerbations.24 In Step 1, to avoid SABA-only treatment,8 the only option is for the patient to take a dose of ICS whenever they take their SABA. This was shown in one study in adults to be similarly effective as taking daily ICS with the dose adjusted every six weeks by a physician or based on exhaled nitric oxide level.25 However, this requires the patient to carry two inhalers with them, which is cumbersome.

Which medications and doses can be used for GINA Track 1?

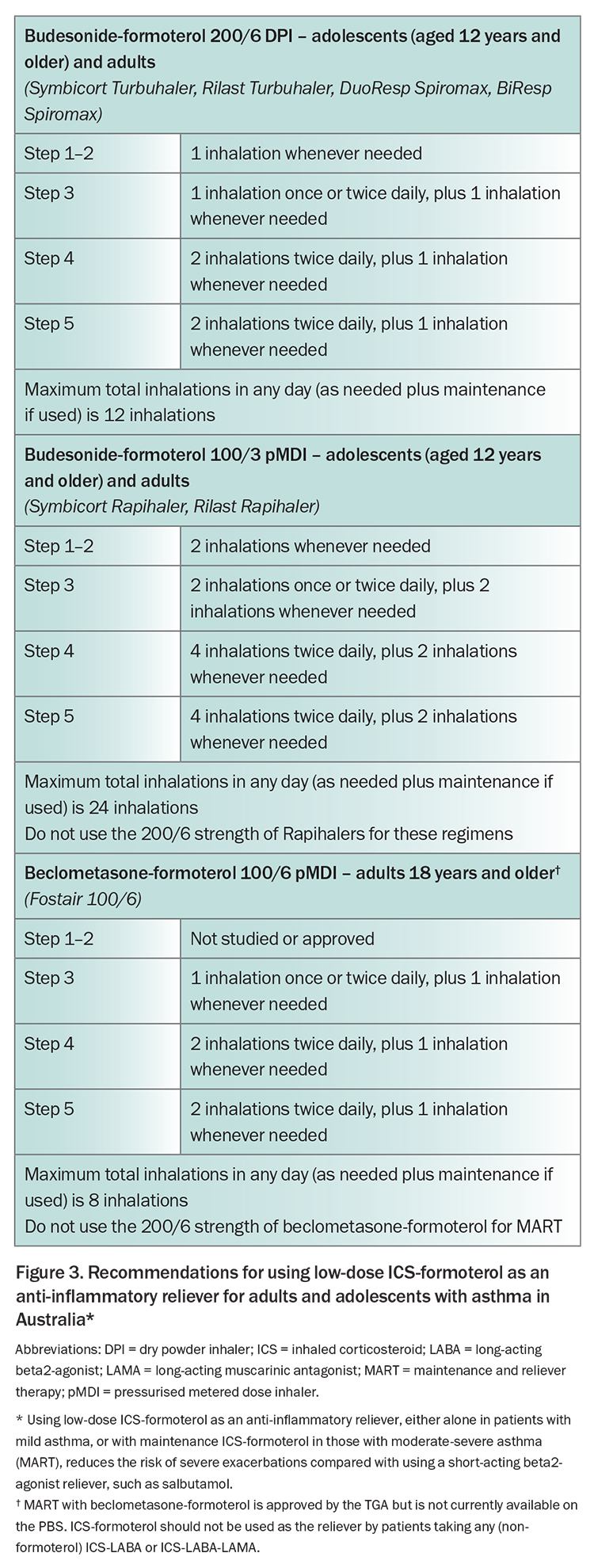

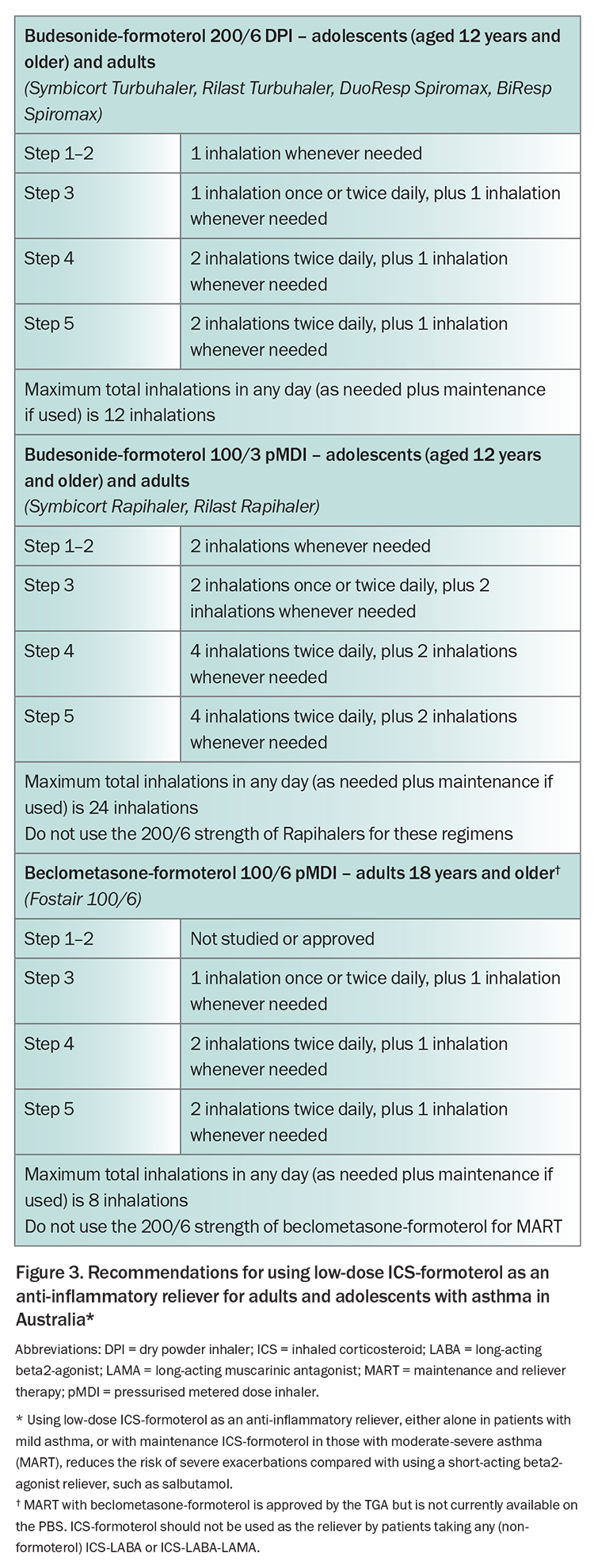

The GINA 2023 report provides specific detail about the medications and doses of ICS-formoterol that can be used across treatment steps in different age groups, as many clinicians may be unfamiliar with how to prescribe it.1 These details are summarised in Figure 3 for Australian formulations and approvals for budesonide-formoterol and beclometasone-formoterol.

How to write an asthma action plan for patients using an ICS-formoterol reliever

Every patient with asthma should have an action plan to provide advice about how to change their medications when their symptoms worsen and when to seek medical attention. The action plan should be written (i.e. printed, pictorial, electronic) rather than only verbal. Many exacerbations are eosinophilic; therefore, the action plan needs to be different depending on whether the patient’s reliever is an ICS-formoterol or a SABA. A library with templates for both types of action plan is available on the National Asthma Council website (https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/health-professionals/asthma-action-plans/asthma-action-plan-library).

Patients using an ICS-formoterol reliever (Track 1)

For these patients, the action plan should instruct them, when symptoms increase, to continue taking an extra dose of their low-dose ICS-formoterol reliever whenever needed for symptom relief, and (for Steps 3 to 5) to continue their usual dose of maintenance ICS-formoterol. Taking as-needed ICS-formoterol whenever asthma symptoms occur markedly reduces the risk of progression to a severe exacerbation over the next days and weeks.26-28 Both the budesonide and the formoterol contribute to this reduction in risk.29 Patients should seek medical care if they are rapidly deteriorating, or if they need more than a specific total number of inhalations in any day, as shown in Figure 3. The action plan for patients using ICS-formoterol reliever, which was developed in Australia, can be used for patients taking either as-needed-only ICS-formoterol or MART with ICS-formoterol.

Patients using a SABA reliever (Track 2)

For these patients, the action plan usually instructs them, when their symptoms worsen, to take extra SABA for symptom relief, using two puffs when needed up to four-hourly, preferably by a spacer. The physician writing the action plan should also advise them to increase their maintenance preventer treatment for at least one to two weeks as follows.1

- Maintenance ICS: in adults and adolescents, consider a large (e.g. four-fold) increase in ICS dose.

- Maintenance ICS-formoterol: consider increasing maintenance ICS-formoterol dose to four times the usual dose. Note the maximum total daily dose in Figure 3.

- Maintenance ICS-LABA with non-formoterol LABA: step up to a higher-dose formulation if available, or consider adding a separate ICS inhaler to achieve a large (e.g. four-fold) increase in the ICS dose.

- Maintenance ICS-LABA-LAMA: consider adding a high dose ICS inhaler.

Patients should seek medical care if they are rapidly deteriorating or need SABA again within three hours.

Oral corticosteroids

The written asthma action plan should also provide instructions for when and how to start OCS, if symptoms are worsening rapidly or not improving after two to three days. To avoid overuse, patients should ideally contact their doctor before they start taking OCS. OCS are preferably taken in the morning to minimise insomnia. For adults, the usual dose is prednisolone 40 to 50 mg, usually for five to seven days, and for children the dose is prednisolone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day up to 40 mg, usually for three to five days. Tapering is not needed if OCS have been taken for less than two weeks. Advise patients about common side effects of short-term OCS use, including sleep disturbance, increased appetite, reflux and mood changes.

Although OCS are life-saving during severe asthma exacerbations, even occasional short courses (e.g. once every two years) are associated with a cumulative increased risk of long-term adverse effects, such as osteoporosis, diabetes, heart disease, cataract and pneumonia.30 Any patient who has had an exacerbation requiring OCS in the past 12 months should have their action plan and asthma therapy reviewed, including inhaler technique, adherence and management of comorbidities. If possible, switch to Track 1 therapy with ICS-formoterol reliever, as this will reduce the chance of another severe exacerbation.

What environmental factors should be considered when choosing inhalers?

There is increasing awareness of the need to address climate change and reduce global warming potential across all areas of health. For asthma, there is a particular focus on reducing prescribing and use of pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pDMIs), as current propellants have about 25 times the global warming potential of dry powder inhalers.31 New propellants with low global warming potential are in development. Although some patients may be able to be switched to a dry powder inhaler, these are not available for all medications in Australia, and they cannot be used by young children or some older patients. In addition, exacerbations requiring ED visits or hospitalisation have a heavy carbon burden. Therefore, GINA emphasises the importance of first choosing the right medication for the individual patient to control their symptoms and reduce their risk of severe exacerbations (including switching to Track 1 treatment if available), then considering which inhalers are available for that medication, which of these the patient can use correctly, and their relative environmental impact. Inhaler technique should be rechecked frequently. The ‘greenest’ inhaler is the one that the patient can use correctly, and that will reduce their risk of severe exacerbations. For patients in whom a pMDI is the only suitable inhaler, be careful to avoid ‘green guilt’, which may impact on adherence and increase the risk of exacerbations.31

What’s new with COVID-19 for patients with asthma?

The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have subsided but Australia still has over 5000 confirmed cases and around 1000 hospitalisations each week. People with asthma are not at increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness, except if they have recently used OCS. COVID-19 vaccination is recommended for all people aged 5 years and older, with boosters recommended for all adults, and for adolescents at increased risk of severe COVID-19. During 2020-2021, a clear decrease in asthma exacerbations was seen, likely due to mask-wearing and social distancing that reduced spread of respiratory infections, including influenza.32

If a person with asthma tests positive for COVID-19, remind them to continue taking their usual asthma medications. Nebulised treatment should be avoided, if possible, because of the risk of transmitting infection to healthcare personnel and the patient’s family. For asthma exacerbations, salbutamol by pMDI and spacer is as effective as a nebuliser for most patients, and with fewer adverse effects. Be cautious if considering ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir for patients taking fluticasone propionate-salmeterol or fluticasone furoate-vilanterol, as the interaction may increase the risk of cardiac adverse effects from the LABA. Instead, consider prescribing molnupiravir if available (although this antiviral is not first-line treatment because it is not as effective for treatment of COVID-19 infection), or switching to an ICS-only or ICS-formoterol inhaler for the duration of antiviral therapy.33 However, if the patient’s inhaler is switched, training them in correct inhaler technique will be required.

Conclusion

The GINA strategy report is updated every year based on a comprehensive review of new evidence across all asthma management, providing clinicians with the most up-to-date evidence-based recommendations for asthma management, that can be adapted for local health systems and medication availability. The GINA 2023 report provides further evidence supporting the prioritisation of as-needed ICS-formoterol as an anti-inflammatory reliever inhaler across treatment steps, to reduce severe exacerbations and treatment-related adverse effects. This strategy has the potential to substantially reduce the currently heavy burden of asthma in Australia, by reducing urgent use of healthcare and OCS. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Reddel or her institute has received research grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Perpetual Philanthropy; consulting fees for providing independent medical advice from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis; and fees for providing independent medical education from Alkem, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, Getz, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi and Teva. She has been on Scientific Advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Sanofi; is a member of the Australian Asthma Guidelines Committee; and is Chair of the Science Committee and member of Board of Directors for the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).

References

1. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention, 2023. GINA, 2023. Available online at www.ginasthma.org/reports (accessed August 2023).

2. Dusser D, Montani D, Chanez P, de Blic J, Delacourt C, Deschildre A, et al. Mild asthma: an expert review on epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment recommendations. Allergy. 2007;62:591-604.

3. Bergstrom SE, Boman G, Eriksson L, et al. Asthma mortality among Swedish children and young adults, a 10-year study. Respir Med 2008; 102: 1335-1341.

4. Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, Baltzan M, Cai B. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 332-336.

5. Suissa S, Ernst P, Kezouh A. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids and the long term prevention of hospitalisation for asthma. Thorax 2002; 57: 880-884.

6. Reddel HK, Busse WW, et al. Should recommendations about starting inhaled corticosteroid treatment for mild asthma be based on symptom frequency: a post-hoc efficacy analysis of the START study. Lancet 2017; 389: 157-166.

7. O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1865-1876.

8. Reddel HK, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management: Treatment of asthma with short-acting bronchodilators alone is no longer recommended for adults and adolescents. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1901046.

9. Reddel HK, Sawyer SM, Everett PW, Flood PV, Peters MJ. Asthma control in Australia: a cross-sectional web-based survey in a nationally representative population. Med J Aust 2015;2 02: 492-497.

10. Reddel HK, Ampon RD, Sawyer SM, Peters MJ. Risks associated with managing asthma without a preventer: urgent healthcare, poor asthma control and over-the-counter reliever use in a cross-sectional population survey. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e016688.

11. Murphy J, McSharry J, Hynes L, Matthews S, Van Rhoon L, Molloy GJ. Prevalence and predictors of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in young adults (15-30 years) with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma 2021; 58: 683-705.

12. Baggott C, Chan A, Hurford S, et al. Patient preferences for asthma management: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037491.

13. Blakey J, Chung LP, McDonald VM, et al. Oral corticosteroids stewardship for asthma in adults and adolescents: A position paper from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology 2021; 26: 1112-1130.

14. Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting β(2)-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901872.

15. Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang HC, et al. Short-acting β(2)-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2101402.

16. Baggott C, Reddel HK, Hardy J, et al. Patient preferences for symptom-driven or regular preventer treatment in mild to moderate asthma: findings from the PRACTICAL study, a randomised clinical trial. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1902073.

17. Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O’Byrne PM, et al. As-needed budesonide-formoterol versus maintenance budesonide in mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1877-1887.

18. Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al. Controlled trial of budesonide-formoterol as needed for mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2020-2030.

19. Hardy J, Baggott C, Fingleton J, et al. Budesonide-formoterol reliever therapy versus maintenance budesonide plus terbutaline reliever therapy in adults with mild to moderate asthma (PRACTICAL): a 52-week, open-label, multicentre, superiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 919-928.

20. Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2018; 319: 1485-1496.

21. Cates CJ, Karner C. Combination formoterol and budesonide as maintenance and reliever therapy versus current best practice (including inhaled steroid maintenance), for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (4): CD007313.

22. Reddel HK, Bateman ED, Schatz M, Krishnan JA, Cloutier MM. A practical guide to implementing SMART in asthma management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: S31-S38.

23. Crossingham I, Turner S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Combination fixed-dose beta agonist and steroid inhaler as required for adults or children with mild asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; (5): CD013518.

24. Williams LK, Peterson EL, Wells K, et al. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 1185-91.e2.

25. Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, King TS, et al. Comparison of physician-, biomarker-, and symptom-based strategies for adjustment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adults with asthma: the BASALT randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 308: 987-997.

26. Bousquet J, Boulet LP, Peters MJ, et al. Budesonide/formoterol for maintenance and relief in uncontrolled asthma vs. high-dose salmeterol/fluticasone. Respir Med 2007; 101: 2437-2446.

27. Buhl R, Kuna P, Peters MJ, et al. The effect of budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy on the risk of severe asthma exacerbations following episodes of high reliever use: an exploratory analysis of two randomised, controlled studies with comparisons to standard therapy. Respir Res 2012; 13: 59.

28. O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Effect of a single day of increased as-needed budesonide-formoterol use on short-term risk of severe exacerbations in patients with mild asthma: a post-hoc analysis of the SYGMA 1 study. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 149-158.

29. Rabe KF, Atienza T, Magyar P, Larsson P, Jorup C, Lalloo UG. Effect of budesonide in combination with formoterol for reliever therapy in asthma exacerbations: a randomised controlled, double-blind study. Lancet 2006; 368: 744-7453.

30. Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy 2018; 11: 193-204.

31. Levy ML, Bateman ED, Allan K, et al. Global access and patient safety in the transition to environmentally friendly respiratory inhalers: the Global Initiative for Asthma perspective. Lancet 2023; S0140-6736(23)01358-2.

32. Davies GA, Alsallakh MA, Sivakumaran S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on emergency asthma admissions and deaths: national interrupted time series analyses for Scotland and Wales. Thorax 2021; 76: 867-873.

33. Carr TF, Fajt ML, Kraft M, et al. Treating asthma in the time of COVID. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; 151: 809-817.