Influenza in 2025: what to expect and how to ameliorate its impact

The influenza seasons from 2022 to 2024 have been moderately severe in Australia. Vaccines to prevent influenza infections and antiviral treatments to both prevent and treat influenza are readily available and are important countermeasures to alleviate the severity of the influenza season; however, declining vaccination rates are increasing the susceptibility of people to this disease.

- The last three influenza seasons in Australia (2022–24) have been moderately severe.

- The severity of each influenza season is hard to predict in advance; therefore, it is wise to prepare for each season beforehand in case it is severe.

- Influenza vaccines provide worthwhile levels of protection against illness and hospitalisation and are our best defence against influenza currently.

- Influenza antiviral drugs should not be forgotten during the peak period of the influenza season, especially for immunocompromised patients.

- Influenza vaccination rates are declining across all age groups in Australia post-COVID-19.

- GPs have an important role in informing their patients about the benefits of influenza vaccination and, where possible, administering vaccines in their own clinics.

The annual cycle of autumn–winter outbreaks of respiratory viruses in Australia is about to begin. What we can learn from past seasons and our efforts to control these diseases, especially influenza, is worth pondering. This article outlines the impact of influenza in the post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) era compared with the pre-pandemic period and examines the potential reasons behind the apparent changing epidemiology of influenza in Australia. It also discusses the uptake of influenza vaccines across different age groups and highlights the differences between Australian states and territories and their approaches to influenza vaccination. The important role that GPs play in delivering influenza vaccines and the decline in this service over the past five years is explored.

Impact of COVID-19 on influenza trends

There have been many changes since the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing outbreaks and epidemics caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which continues to circulate in an irregular pattern throughout the Australian community. From an influenza perspective, annual epidemics returned shortly after pandemic restrictions were removed and we have now had three above-average influenza seasons compared with the pre-pandemic period. In fact, 2024 saw the highest number of laboratory-confirmed cases reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) on record.

The NNDSS is a system run by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care that records all 71 diseases that are notifiable in Australia, including influenza. It is updated daily and can be publicly accessed through the NNDSS dashboard.1 This dashboard provides data for each disease listed with the ability to select from the number of notified cases for one or more diseases, as well as by state and territory, by year, by month, by date range, by age group and by sex. Laboratory-confirmed influenza cases have been notifiable since 2001 but were not well recorded until the last 10 years. It should be remembered that only patients who have had a positive laboratory test result for influenza are recorded on the NNDSS and only a small proportion of symptomatic patients will present to a medical facility and be tested, maybe in the range of 5 to 10%, but this percentage is only a ‘guesstimate’. After the collection of many years of influenza NNDSS data, it is clear that children appear to be over-represented in the statistics, probably because sick children are more likely to be seen by a doctor and tested than adults or elderly individuals.

NNDSS influenza data before the COVID-19 pandemic period revealed an average of 163,005 (all ages) laboratory-confirmed influenza cases in 2015–19. The following are the figures after the COVID-19 pandemic period:

- 233,454 in 2022

- 289,152 in 2023

- 365,590 in 2024

- 48,101 up to 31 March 2025.1

Factors contributing to the higher number of influenza cases

What is the reason behind the apparently ‘big’ influenza seasons for the last three years in a row from 2022 to 2024 when ‘big’ influenza seasons only occurred every two to three years previously? Some clear changes are the increased testing post-COVID-19 and the expansion of respiratory multiplex testing, which tests for multiple pathogens, usually combining the big three: influenza A and B, SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory syncytial virus. For some tests, other common respiratory viruses and bacteria are also included. These changes might well explain the increase in numbers from before to immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, but further large increases in testing were less likely during the 2022–24 period. Unfortunately, the number of tests for influenza performed is not available from the NNDSS, as only positive influenza cases are recorded; therefore, we do not know the denominator in these statistics.

After the COVID-19 pandemic period, the NNDSS data showed moderate to high numbers of deaths associated with influenza (308 deaths in 2022, 599 in 2023, 1002 in 2024), which were higher than numbers in most years before the COVID-19 pandemic period, with the exception of 2017 (1181 deaths) and 2019 (902 deaths).2 These mortality statistics are again an underestimate of actual deaths associated with influenza infections, because of an absence of testing and the fact that those associated deaths may have occurred after the initial infection and are not recorded.

Increased population is another factor driving the influenza case numbers higher, with an increase of about 2 million (8%) people in Australia between 2019 and 2024. The co-circulation of multiple influenza subtypes and types in 2024, A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2), and in 2023, A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B, may have also led to an increased number of cases. In 2022, influenza had ‘returned’ after a two-year absence, meaning more people were likely to be susceptible, especially since A(H3N2) viruses predominated. Influenza vaccination rates have also been dropping in recent years, which may have also had a small effect on influenza case numbers. Home testing for influenza using rapid antigen tests has also increased post-COVID-19, but data from these tests are not collected by the NNDSS. Based on the available evidence, it would seem that influenza case numbers have indeed been high for the past three years. It remains to be seen whether this is still a remnant of the lack of exposure and subsequent herd immunity to annual influenza epidemics that did not occur in 2020 and 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, or if these ‘bigger’ influenza seasons are the new ‘normal’ seasons.

Trends in influenza vaccination rates

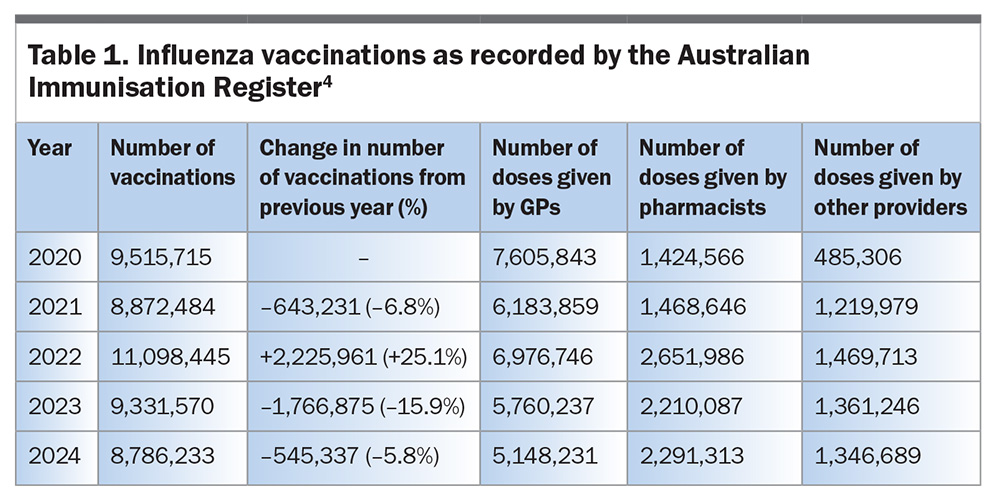

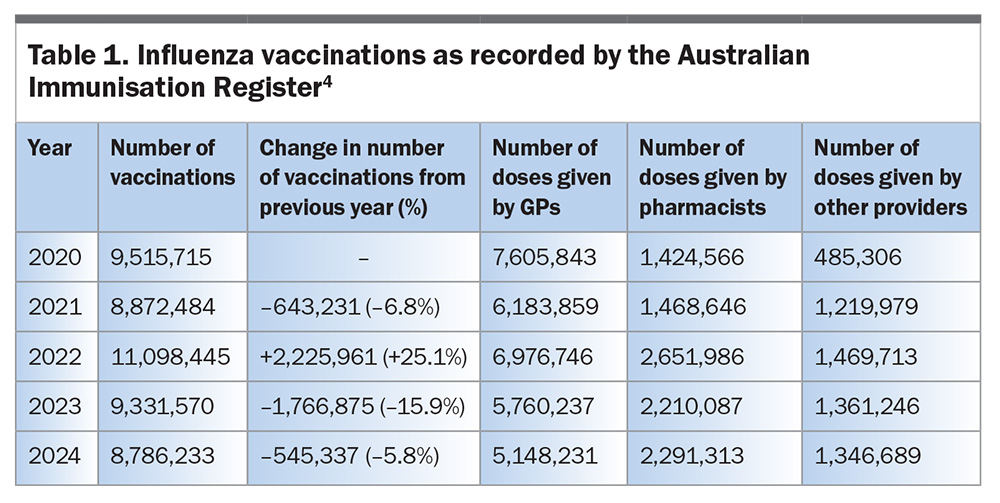

Given that we are likely to encounter a significant number of influenza infections in 2025 (with the first 3 months already 59% above the 2024 case numbers at the same time of year), it remains extremely difficult to predict the severity of an influenza season in advance. So, what can we do to better protect individuals and the community from influenza this season? Vaccination remains the best measure to ameliorate the impact of influenza, even though the protection it affords is only moderate. For example, a US meta-analysis of 12 influenza seasons including ten randomised controlled trials, showed a pooled vaccine efficacy of 59% (95% confidence interval [CI], 51–67%) in adults aged 18 to 65 years.3 Similar vaccine effectiveness (VE) figures were reported for Australia in 2024 with a VE of 62% (95% CI, 45–74%) against general practice attendance with influenza and a VE of 56% (95% CI, 48–63%) against hospitalisation with influenza in studies by the Australian Sentinel Practices Research Network and Influenza Complications Alert Network, respectively.2 The total number of Australian influenza vaccinations recorded for the past five years (2020–24) from 1 March to 6 October each year as reported to the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) are presented in Table 1.4 These data show fluctuating numbers of vaccinations administered over this period, with the highest numbers occurring in 2022 (about 43% of the population vaccinated) and reductions occurring in 2023 (about 35% of the population) and again in 2024 (about 32% of the population).

Other data from the AIR show that the number of vaccines given by GPs has dramatically reduced by 32% over this period and this has only been partially balanced by the increased numbers of vaccines being given through pharmacies.4 Although the number of vaccines given by pharmacists has increased by 60.8% over this period, it has not replaced the number of doses previously administered by GPs.4 The reduced numbers of vaccinations being administered by GPs may reflect difficulties in patients accessing these facilities, as well as practices choosing not to give or promote influenza vaccinations. As public surveys have shown in the past, recommendations from GPs have the strongest impact on patients getting vaccinated. This is something GPs could focus on in 2025 in a bid to improve vaccination rates, especially for those age groups at the highest risk of severe influenza or complications arising from influenza infections.

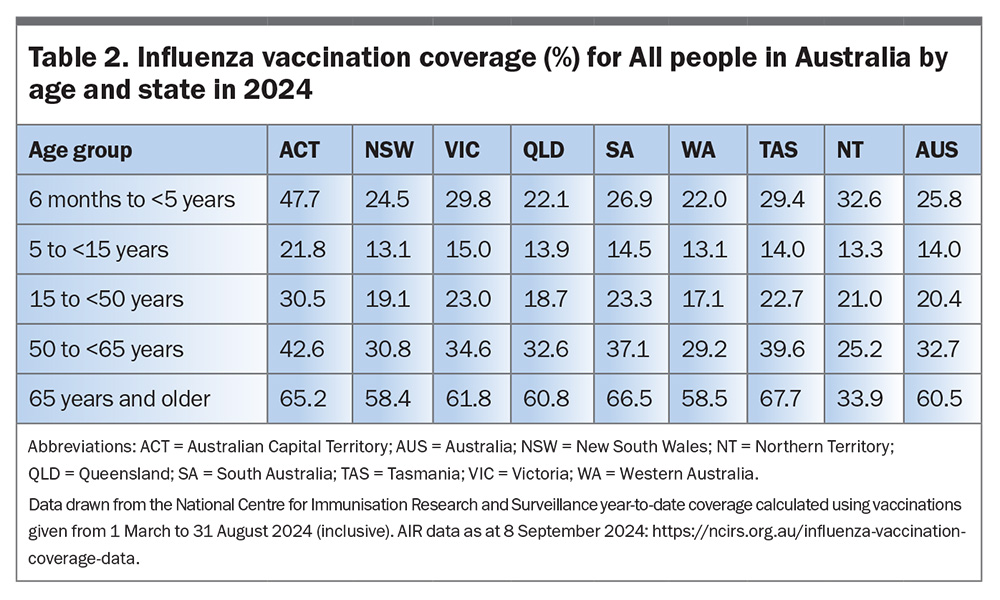

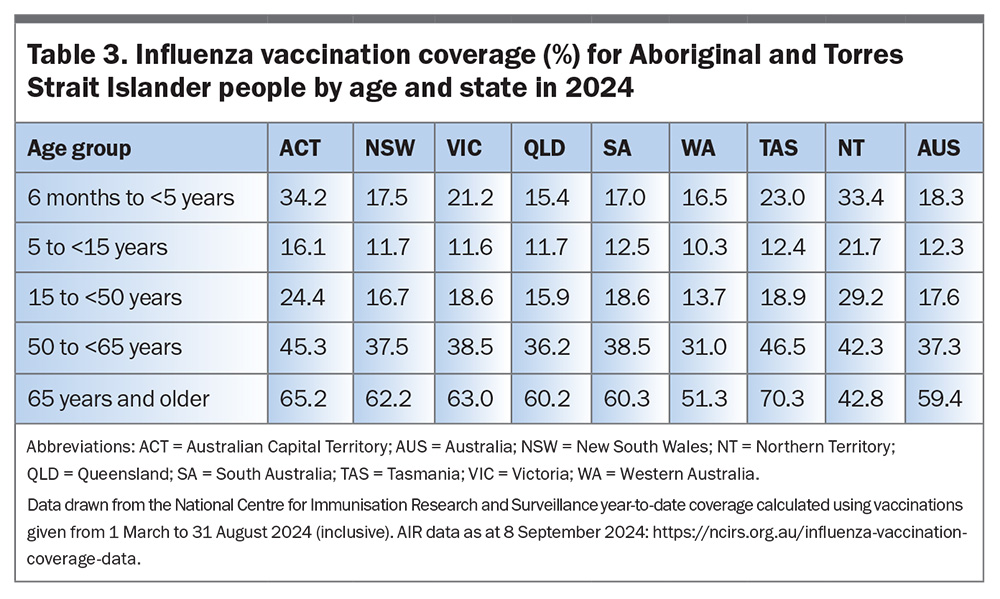

Influenza vaccination rates have also varied between states and territories in Australia, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3 for 2024 with data compiled by the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) from the AIR.4,5 The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) had the highest vaccination rates in Australia for all age groups, except for those aged 65 years and older, whereas Tasmania had a slightly higher rate (67.7% vs 65.2%). The vaccination rate for those aged 6 months to younger than 5 years was especially notable, with the ACT achieving a 47.7% rate, whereas most other jurisdictions only achieved rates from 22.0% (Western Australia [WA]) to 32.6% (Northern Territory [NT]). AIR influenza vaccination rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were generally lower than that for All Australians across all the age groups, with the exception of those aged 65 years and older, which showed similar rates to those for All people (59.4% vs 60.5%). On a state or territory basis, NT had significantly higher vaccination rates in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 5 to younger than 15 years (21.7%) and 15 to younger than 50 years (29.2%), whereas Tasmania had a higher vaccination rate for those aged 65 years and older (70.3%) compared with other jurisdictions. States with lower vaccination rates may be able to learn from states with higher vaccination rates, but it is clear that a national program is needed to achieve a significant increase in influenza vaccine uptake in the future.

This general trend in decreasing influenza vaccination rates has also been seen in the USA, where the number of influenza doses distributed has dropped from 175.62 million doses in 2021–22 to 146.22 million doses in 2024–25 (as of 25 January 2025).6 As of 1 February 2025, 45.7% (95% CI, 44.2–47.2%) of US children aged 6 months to 17 years received an influenza vaccine; this was lower than last season at the same time point (50.2%), as were rates in those aged 65 years and older (utilising the Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries), which dropped from 54.5% in 2023–24 to 51.1% in 2024–25. The influenza vaccination rates for adults (aged 18 to 64 years) and pregnant women were similar in 2024–25 to those in the previous year (45.0% and 37.2%, respectively).6

In recent years, there have been various programs offering free influenza vaccinations for all age groups on top of groups already eligible for free vaccination through the Australian Federal Government’s National Immunisation Program (NIP). This covers individuals aged 65 years and older, children aged 6 months to younger than 5 years, pregnant women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people with a range of comorbidities.7 In 2022, all states apart from ACT and NT supported some form of free influenza vaccines for everyone; along with a strong media campaign, this resulted in the highest uptake of influenza vaccines on record (Table 1). In 2023 and 2024, only WA and Queensland (QLD) offered free influenza vaccinations for people of all ages. This unfortunately did not have the desired effect, with WA showing reductions in vaccination rates in both 2023 (–9.2%) and 2024 (–15.3%) compared with the previous years. There were also similar results in QLD (–13.2% in 2023, –4.6% in 2024) with these QLD reductions being slightly better than NSW in 2023, but comparable in 2024, when free vaccination was not offered for all ages (–18.5% in 2023, –4.9% in 2024).4

Vaccine hesitancy

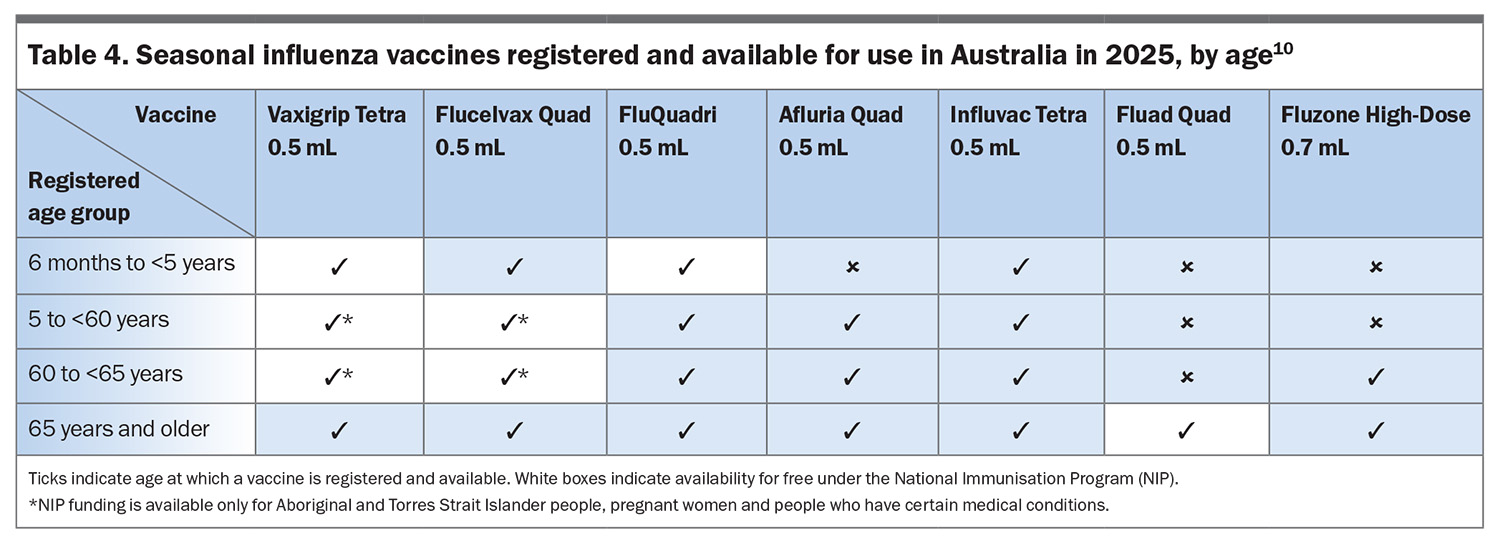

Why would free vaccinations not entice more people to take up this offer? Vaccine hesitancy has been identified as a major issue post-COVID-19, and this may partially explain the lower vaccination rates in all jurisdictions.8 Reversing this trend may be challenging in coming years. Both WA and QLD are again continuing their free influenza vaccination program for all ages in 2025, but this is clearly not the only answer to improving rates. A concerted effort from all sectors of medicine, pharmacy, State governments and Federal governments will be required to prevent influenza vaccination rates dropping even further in 2025. No new influenza vaccines will be available on the Australian market in 2025; however, it is expected that FluMist will be available in Australia in 2026. FluMist is a live attenuated vaccine that is especially suitable for children 2 years of age and older, as it is administered intranasally instead of by injection. This may help to improve vaccine uptake and prevent infections and hospitalisation among young children as it has in the UK in recent years.9 The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) have released their clinical advice on the administration of seasonal influenza vaccines in 2025, listing all influenza vaccines available in Australia in 2025 and the age groups suitable for each vaccine (Table 4).10

Antivirals for influenza management

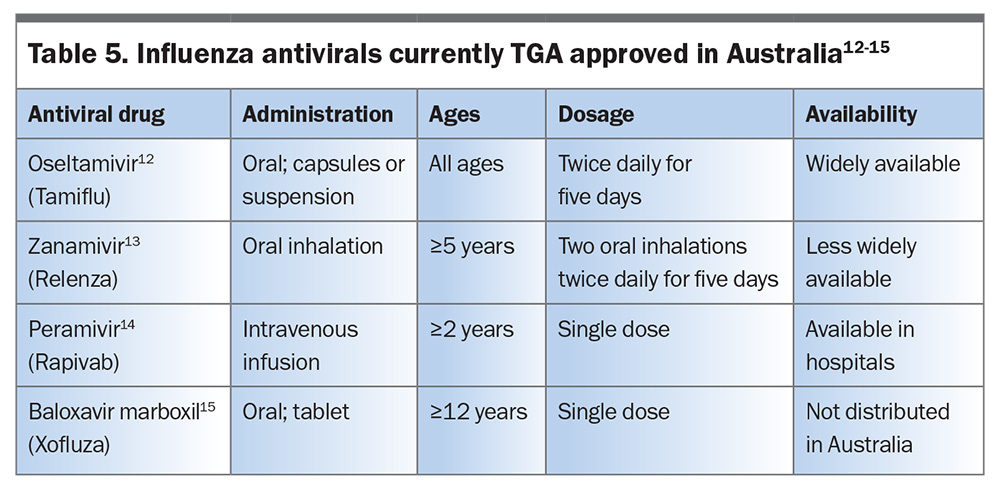

Given the downward trend in influenza vaccinations, the potential of yet another ‘big’ year of influenza infections in 2025, with the high number of influenza cases already reported and the extreme influenza season in the USA in 2024–25, we must prepare for the Australian influenza season now.1,11 It is also worth reminding GPs and the general public that antivirals are available for the treatment of influenza, which can effectively reduce the symptoms of influenza if given within 48 hours of symptom onset (Table 5).12-15 In addition, these antivirals can be given prophylactically to people who may have been exposed or to prevent infection in vulnerable individuals, such those who are immunocompromised, frail or unvaccinated. These drugs still need to be prescribed by a GP or nurse practitioner in Australia, unlike in New Zealand, where they are available over the counter in pharmacies during the prescribed influenza season. The prophylactic use of these drugs is particularly important in residential institutions, such as aged care communities, where they have been shown to reduce the impact of influenza outbreaks.

Conclusion

In 2025, both vaccines to prevent and antivirals to prevent and treat influenza should be important parts of the countermeasures that are implemented in Australia, along with strong promotion for these measures by the State and Federal governments, to reverse the current trend of reduced vaccinations and to combat another potentially ‘big’ influenza season. GPs, nurse practitioners and pharmacists must also play their part in ameliorating the impact of the coming influenza epidemic this year. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Barr holds shares with a vaccine-producing company.

References

1. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). National Communicable Disease Surveillance Dashboard. Canberra: NNDSS; 2025. Available online at: https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi-dashboard/ (accessed April 2025).

2. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Respiratory Surveillance Reports – 2024. Canberra: Australian Department of Health and Aged Care; 2025. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/australian-respiratory-surveillance-reports-2024 (accessed April 2025).

3. Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12: 36.

4. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Influenza immunisation data. Canberra: Australian Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/immunisation-data/influenza-immunisation-data (accessed April 2025).

5. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Australia (NCIRS). Influenza vaccination coverage data. Sydney: NCIRS; 2025. Available online at: https://ncirs.org.au/influenza-vaccination-coverage-data (accessed April 2025).

6. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Weekly Flu Vaccination Dashboard. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2025. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/dashboard/index.html (accessed April 2025).

7. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Immunisation Program Schedule. Canberra: Australian Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule (accessed April 2025).

8. Davey SA, Elander J, Woodward A, Head MG, Gaffiero D. Understanding barriers to influenza vaccination among parents is important to improve vaccine uptake among children. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2025; 21: 2457198.

9. Boddington NL, Mangtani P, Zhao H, et al. Live-attenuated influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in children aged 2-6 years, the first three seasons of the childhood influenza vaccination program in England, 2013/14-2015/16. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022; 5: 897-905.

10. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. ATAGI statement of the administration of seasonal influenza vaccines in 2025. Canberra: Australian Department of Health and Aged Care; 2025. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/atagi-statement-on-the-administration-of-seasonal-influenza-vaccines-in-2025-0 (accessed April 2025).

11. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Weekly US Influenza Surveillance Report: Key Updates for Week 8, ending February 22, 2025. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2025. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/surveillance/2025-week-08.html (accessed April 2025).

12. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Product Information: Tamiflu® (oseltamivir phosphate). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/188016 (accessed April 2025).

13. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Product Information: RELENZA ROTADISK (zanamivir). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2019. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/66962 (accessed April 2025).

14. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Product Information: RAPIVAB™ (PERAMIVIR). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2021. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/285559 (accessed April 2025).

15. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Product Information: Xofluza® (baloxavir marboxil) tablets. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/317240 (accessed April 2025).