Silicosis in Australia: recent developments and future challenges

Australia has seen an alarming increase in the rate of silicosis among workers in the artificial stone benchtop industry since the first local case was reported in 2015. A world-first ban on the use of artificial stone in Australia from July this year is therefore a welcome development, but health monitoring is still needed for workers with historical silica exposure and those in other industries who remain at risk of developing disease, to ensure silicosis is identified and appropriately managed.

- Since 2015, there has been a major outbreak of silicosis among workers in the artificial stone benchtop industry.

- After a lengthy campaign by doctors, trade unions and workers, Australia recently became the first country to ban the use of artificial stone (containing 1% or more crystalline silica) to produce benchtops.

- In addition to the stone benchtop industry, workers in a wide range of other industries are regularly exposed to occupational silica and require ongoing health monitoring.

- Identifying workers at risk of silica-related disease is important in many clinical situations and can be aided by routine occupational history-taking.

- For those diagnosed with silicosis, the possibility of accessing support through workers compensation insurance should be discussed, and affected workers provided with individualised care in collaboration with a respiratory physician.

Silicosis is an entirely preventable occupational disease that has been diagnosed at an alarming rate in recent years, in one of Australia’s worst outbreaks of occupational lung disease. The recent emergence of silicosis has primarily affected workers who fabricate and install artificial (engineered) stone kitchen benchtops. More than 570 Australian workers from the artificial stone benchtop industry have already been identified as having this irreversible condition.1 Hundreds more have been exposed to dangerous levels of silica, which will result in risk of contracting disease for decades to come.1,2

Following a years-long campaign driven by doctors, trade unions and workers, in July 2024, Australia became the first country in the world to ban the use of artificial stone (containing 1% or more crystalline silica) to produce benchtops.3 Although elimination of this hazard is a welcome development, more work is needed to both improve treatment options for patients with silicosis and monitor the health of silica-exposed workers from the stone benchtop industry and from many other at-risk industries.

Background

Silica is abundantly present in natural materials, such as rock, sand and soil, but also in manufactured products, including bricks, tiles and concrete. Silica becomes an occupational respiratory hazard when respirable-sized particles are generated from these sources and inhaled. Industrial sectors traditionally associated with risk of silica exposure include construction, quarry work and mining.4 Inhalation of respirable crystalline silica can lead to serious respiratory disease, most notably silicosis, which was first described in 1871 and is characterised by chronic inflammation and scarring, predominantly in the upper lobes of the lungs.5,6 There are three forms of silicosis:

- chronic silicosis, which is the most common form and typically progresses slowly after long durations of low-level silica exposure

- accelerated silicosis, which develops less than 10 years after higher levels of silica exposure

- acute silicosis, which results from short durations of very high levels of silica exposure and is associated with high mortality rates.6,7

In addition to silicosis, silica dust exposure is associated with other respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sarcoidosis and lung cancer.6,8 Silica exposure has also been implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.9

Artificial stone is a building material that is primarily used in the fabrication of kitchen and bathroom benchtops and typically has a silica content of about 90%.10 It was introduced to Australia in the early 2000s and, by 2023, commanded an estimated 55% market share due to factors including price, aesthetics and durability.11

The first case of artificial stone-associated silicosis was reported in Spain in 2010.12 Evidence of risk in this industry subsequently mounted, with an increasing number of cases reported around the world.13-15 Silicosis was first reported in the Australian stone benchtop industry in 2015 and, alarmingly, by 2022, almost 600 cases had been identified.1,16 Compared with silicosis caused by natural sources of silica, such as in mining, artificial stone silicosis has been found to develop after shorter periods of exposure and is associated with faster disease progression and higher mortality rates.17 Recently, cases of autoimmune disease associated with silica dust exposure have also been identified in artificial stone benchtop industry workers.4,18

Recent developments

Since the first reports of artificial stone-associated silicosis in Australia, health screening has identified a high prevalence of the disease (28%) in this cohort of workers.19 In this context, Safe Work Australia released a report in August 2023 recommending prohibition of the use of artificial stone.11 In October 2023, the Australian Council of Trade Unions also resolved to ban union members from transporting or using artificial stone on building sites across Australia.20 Subsequently, federal, state and territory governments unanimously agreed to the Safe Work Australia recommendations in December 2023, with most jurisdictions starting the prohibition on 1 July 2024.21

Following recommendations from the National Dust Disease Taskforce, the federal Department of Health and Aged Care launched a National Occupational Respiratory Disease Registry in May 2024.22 All occupational physicians and respiratory physicians in Australia are now required to notify new diagnoses of silicosis to this registry through the online Physician Portal.23,24

Clinical implications

The nationwide ban on artificial stone is a major success for Australian public health. However, the effects of silica exposure can be delayed for many years, if not decades, after the exposure has occurred.25 Furthermore, it is estimated that more than 300,000 Australian workers from a wide range of other industries are regularly exposed to occupational silica and require periodic health monitoring.26 As such, clinicians must be prepared to manage the effects of historical exposure for artificial stone benchtop workers and be aware of workers in other industries who remain exposed and require health monitoring. This periodic monitoring is a duty of the employer to arrange and should be done in accordance with best practice.27

Identification of patients at risk of silica-related disease is indicated in all clinical settings. Best practice involves:

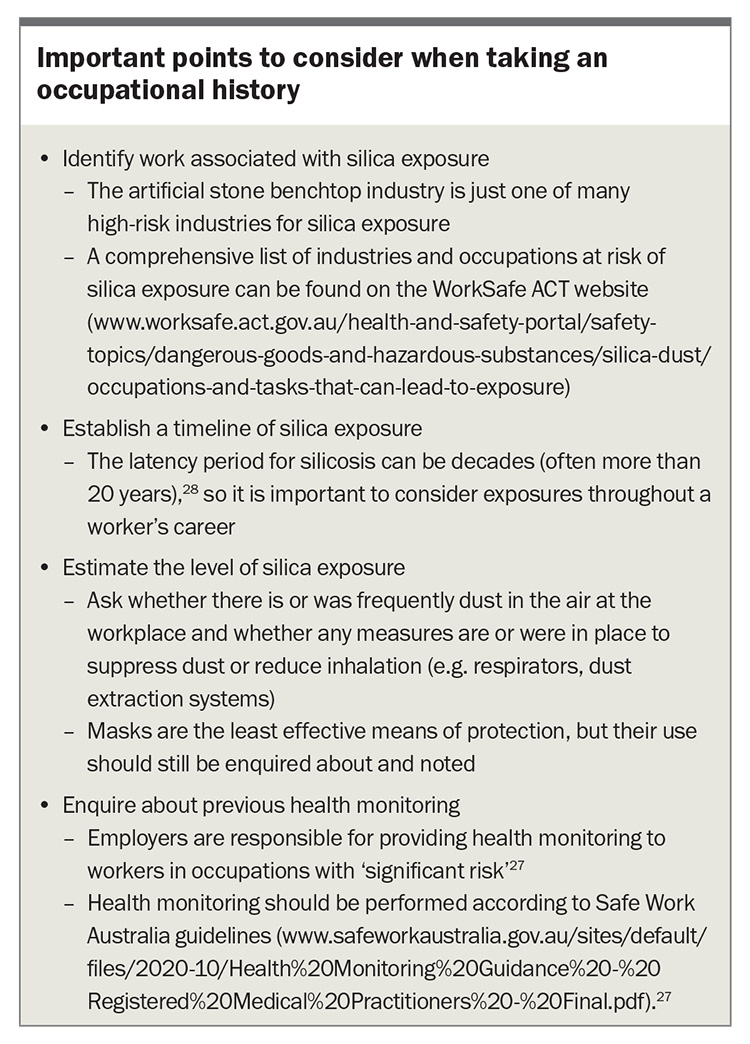

- taking an occupational history from all patients – specific aspects of occupational history to identify patients at risk of silica-associated diseases are summarised in the Box

- considering occupational exposure to silica as a potential cause of a patient’s lung disease, noting that radiological features of silicosis can be similar to those of other lung diseases, including tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and lung cancer29

- considering other diseases that may be associated with silica exposure, such as autoimmune disease (e.g. silica exposure has been implicated in more than half of men with systemic sclerosis in a large European study).30

GPs are often involved in health surveillance of workers who are or were previously exposed to silica dust. Although guidelines for the surveillance of previously exposed workers are yet to be developed, clinicians should be aware that any worker with historical exposure will remain at risk of silica-related disease for decades to come. Encouraging smoking cessation is particularly important for silica-exposed workers, as smoking adds to the risk of silicosis and lung cancer. For workers who remain exposed to silica and where concerns are identified about inadequate dust control measures in the workplace, consider encouraging the patient to discuss these with the state or territory workplace health and safety regulatory agency. If silicosis is suspected, referral of patients to a respiratory physician with expertise in occupational lung diseases is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and discuss management.

Diagnosing silicosis is essential to provide appropriate management, which will include measures to prevent further silica exposure. Through the work of the national registry and regulatory agencies, it is hoped that identification of a patient with silicosis will be followed by an investigation to identify and protect other at-risk workers in the same workplace and industry, although the mechanism for this has not yet been made clear. For patients diagnosed with silicosis, it is important to discuss the possibility of accessing support through workers compensation insurance, particularly for migrant workers who may not be aware of this possibility. Treatments for silicosis are in development, and affected workers may be eligible for participation in clinical trials through specialist clinics.

Conclusion

The nationwide ban on artificial stone across Australian worksites is a notable milestone that will eliminate a hazardous source of silica exposure for thousands of workers. However, workers in other industries continue to be at risk of silica exposure, and those with a past history of high-risk work will remain at risk of silicosis for many years, given the latency from exposure to disease of up to two decades or more. These workers also require monitoring for other conditions associated with silica exposure, such as autoimmune disease. All clinicians have a role in identifying silica-related disease, through either routine practice or more formal periodic monitoring arranged by employers. As our understanding of occupational silica exposure continues to improve, it is essential to incorporate best practices for investigation and management of affected workers and to connect them to appropriate supports. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Hoy RF, Sim MR. Correspondence on ‘Demographic, exposure and clinical characteristics in a multinational registry of engineered stone workers with silicosis’ by Hua et al. Occup Environ Med 2022; 79: 647-648.

2. Hoy RF, Baird T, Hammerschlag G, et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis: a rapidly emerging occupational lung disease. Occup Environ Med 2018; 75: 3-5.

3. Kolovos B. ‘Dangerous product’: Australian ban on engineered stone to begin next year. The Guardian, 13 December 2023. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/dec/13/engineered-stone-bench-top-ban-confirmed-begin-2024-when (accessed August 2024).

4. Barnes H, Goh NSL, Leong TL, Hoy R. Silica-associated lung disease: an old-world exposure in modern industries. Respirology 2019; 24: 1165-1175.

5. Hoy RF, Jeebhay MF, Cavalin C, et al. Current global perspectives on silicosis—Convergence of old and newly emergent hazards. Respirology 2022; 27: 387-398.

6. Leung CC, Yu ITS, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet 2012; 379: 2008-2018.

7. Greenberg MI, Waksman J, Curtis J. Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon 2007; 53: 394-416.

8. Graff P, Larsson J, Bryngelsson I-L, Wiebert P, Vihlborg P. Sarcoidosis and silica dust exposure among men in Sweden: a case–control study. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e038926.

9. Miller FW, Alfredsson L, Costenbader KH, et al. Epidemiology of environmental exposures and human autoimmune diseases: findings from a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Expert Panel Workshop. J Autoimmun 2012; 39: 259-271.

10. Ophir N, Shai AB, Alkalay Y, et al. Artificial stone dust-induced functional and inflammatory abnormalities in exposed workers monitored quantitatively by biometrics. ERJ Open Res 2016; 2: 00086-2015.

11. Safe Work Australia. Decision regulation impact statement: Prohibition on the use of engineered stone. Canberra: SWA; 2023. Available online at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/decision_ris_-_prohibition_on_the_use_of_engineered_stone_-_27_october_2023.pdf (accessed August 2024).

12. Martínez C, Prieto A, García L, Quero A, González S, Casan P. Silicosis: a disease with an active present. Arch Bronconeumol 2010; 46: 97-100.

13. Pérez-Alonso A, Córdoba-Doña JA, Millares-Lorenzo JL, Figueroa-Murillo E, García-Vadillo C, Romero-Morillos J. Outbreak of silicosis in Spanish quartz conglomerate workers. Int J Occup Environ Health 2014; 20: 26-32.

14. Pascual S, Urrutia I, Ballaz A, Arrizubieta I, Altube L, Salinas C. Prevalence of silicosis in a marble factory after exposure to quartz conglomerates. Arch Bronconeumol 2011; 47: 50-51.

15. Kramer MR, Blanc PD, Fireman E, et al. Artificial stone silicosis [corrected]: disease resurgence among artificial stone workers. Chest 2012; 142: 419-424.

16. Frankel A, Blake L, Yates D. LATE-BREAKING ABSTRACT: Complicated silicosis in an Australian worker from cutting engineered stone countertops: an embarrassing first for Australia. Eur Respir J 2015; 46 (Suppl 59): PA1144.

17. Wu N, Xue C, Yu S, Ye Q. Artificial stone-associated silicosis in China: a prospective comparison with natural stone-associated silicosis. Respirology 2020; 25: 518-524.

18. Shtraichman O, Blanc PD, Ollech JE, et al. Outbreak of autoimmune disease in silicosis linked to artificial stone. Occup Med (Lond) 2015; 65: 444-450.

19. Hoy RF, Dimitriadis C, Abramson M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for silicosis among a large cohort of stone benchtop industry workers. Occup Environ Med 2023; 80: 439-446.

20. Australian Council of Trade Unions. The trade union movement says ban engineered stone or we will [media release]. Melbourne: ACTU; 2023. Available online at: https://www.actu.org.au/media-release/the-trade-union-movement-says-ban-engineered-stone-or-we-will/ (accessed August 2024).

21. Australian Government Department of Employment and Workplace Relations. Prohibition on the use of engineered stone. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024. Available online at: https://www.dewr.gov.au/engineeredstone (accessed August 2024).

22. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. About the National Occupational Respiratory Disease Registry. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/nordr/about (accessed August 2024).

23. Royal Australasian College of Physicians. National Occupational Respiratory Disease Registry. Sydney: RACP; 2024. Available online at: https://www.racp.edu.au/news-and-events/all-news/news-details?id=2304bbaf-bbb2-61c2-b08b-ff01001c3177&_zs=nbU9l&_zl=cWCu2 (accessed August 2024).

24. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Occupational Respiratory Disease Registry. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024. Available online at: https://nordr.health.gov.au/ (accessed August 2024).

25. Akgun M, Araz O, Ucar EY, et al. Silicosis appears inevitable among former denim sandblasters: a 4-year follow-up study. Chest 2015; 148: 647-654.

26. Si S, Carey RN, Reid A, et al. The Australian Work Exposures Study: prevalence of occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica. Ann Occup Hyg 2016; 60: 631-637.

27. Safe Work Australia. Health monitoring: Guide for registered medical practitioners. Canberra: SWA; 2018. Available online at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/Health%20Monitoring%20Guidance%20-%20Registered%20Medical%20Practitioners%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed August 2024).

28. NIOSH Hazard Review: Health effects of occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No: 2002-129.

29. Fazio JC, Gandhi SA, Flattery J, et al. Silicosis among immigrant engineered stone (quartz) countertop fabrication workers in California. JAMA Intern Med 2023; 183: 991-998.

30. De Decker E, Vanthuyne M, Blockmans D, et al. High prevalence of occupational exposure to solvents or silica in male systemic sclerosis patients: a Belgian cohort analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37: 1977-1982.