Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in a primary care setting: what do GPs need to know?

Bronchiectasis is a clinical syndrome characterised by cough, sputum production and recurrent bronchial infection. Mainstays of management include preserving lung function, minimising respiratory exacerbations, reducing symptoms, preventing complications and optimising quality of life.

- Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung condition in which the airways are permanently widened because of episodes of recurrent infection and chronic inflammation.

- The most common symptoms are chronic cough, sputum production and breathlessness.

- The recommended initial investigations include blood tests, sputum culture and high-resolution CT.

- Management of bronchiectasis involves nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies.

- The choice of antibiotic for the management of exacerbations should be based on sputum microscopy and culture results.

- Specialist referral is recommended for severe bronchiectasis, frequent exacerbations, haemoptysis, the development of pulmonary hypertension, immunosuppressed patients, atypical organisms observed on culture or moderate disability secondary to bronchiectasis.

Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung condition involving abnormal, irreversible dilatation of the bronchi where the elastic and muscular tissue is destroyed by acute or chronic inflammation and infection. This is identified radiologically on CT imaging.1,2 The damage leads to the impaired drainage of mucus, which can result in chronic infection leading to airway obstruction.3 Bronchiectasis as a clinical syndrome is characterised by cough, sputum production and recurrent bronchial infection. This article discusses the pathophysiology, causes, presentation, management and natural progression of bronchiectasis. It also describes bronchiectasis exacerbations and recommendations for when to refer patients to a respiratory specialist.

Terminology

In patients without cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis is known as non-cystic fibrosis-associated (non-CF) bronchiectasis. Along with more ‘classical’ bronchiectasis with recurrent infection, bronchiectasis may also present as a radiological diagnosis secondary to lung pathology, resulting in traction and expansion of bronchi without recurrent infective insults (i.e. ‘traction’ bronchiectasis).

Epidemiology of bronchiectasis

The exact prevalence of bronchiectasis worldwide is unknown; however, it has been estimated to be 53 to 566 cases per 100,000 people.1 The prevalence increases with age and in women.1 Non-CF bronchiectasis is more common among the Indigenous populations of Australia and New Zealand. The overall prevalence has decreased following the introduction of childhood vaccinations, improved living conditions and antibiotic availability, but the condition remains common in underprivileged and migrant communities.

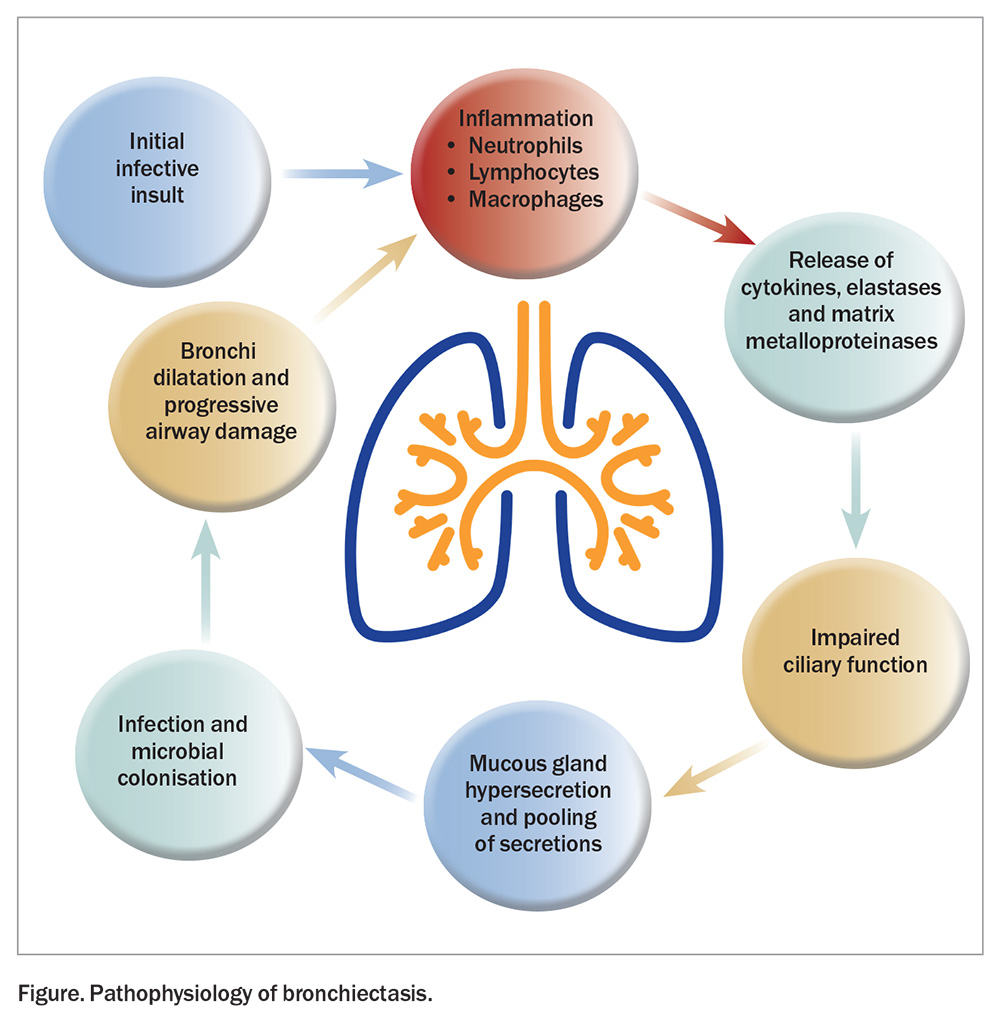

Pathophysiology of non-CF bronchiectasis

Non-CF bronchiectasis is caused by episodes of recurrent infection and chronic inflammation. The process is initiated by an infective insult, followed by inflammation and the release of cytotoxic inflammatory mediators resulting in progressive airway destruction (Figure). This results in the infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages into the airways.1 Neutrophils release inflammatory cytokines, elastases and matrix metalloproteinases, which destroy the bronchial elastin and supporting lung structures, contributing to permanent dilatation of the bronchi.4 The airway walls then thicken because of the normal mucosal and muscular layers being replaced by oedema, ulceration or fibrosis. In the proximal airways, the structural cartilage may be diminished, provoking a reduction in the supportive structure. Neutrophils also alter the function of the cilial epithelium, leading to impaired ciliary beat frequency and mucous gland hypersecretion.4 These changes in airway structure and function contribute to mucus pooling and the self-perpetuating cycle of infection and inflammation, which promote progressive airway damage, microbial colonisation and recurrent infections.

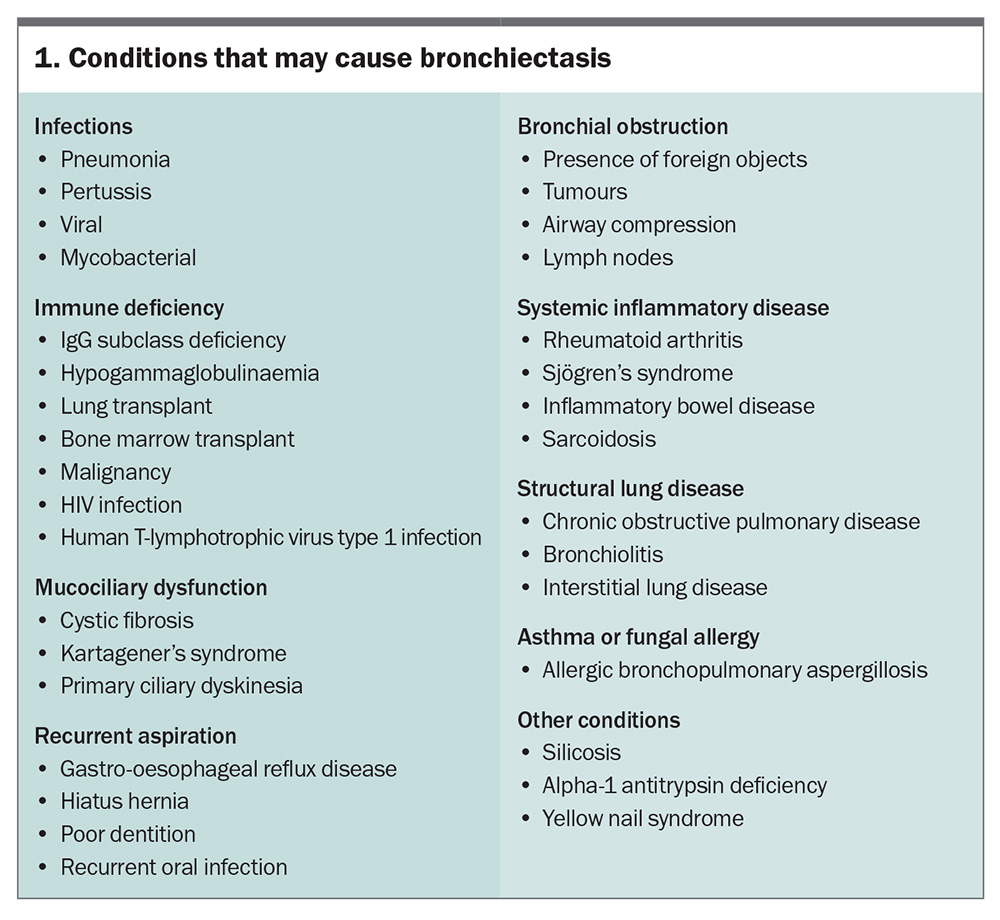

Causes of bronchiectasis

Identifying any underlying cause of bronchiectasis is essential to guide therapy. However, a cause is not identified in up to 50% of cases, which are classified as ‘idiopathic’. It is likely that these cases, however, involve an underlying immune defect, for which there is no effective test for identification.3 History-taking and clinical examination are key to identifying a possible cause, of which the most common to consider are listed in Box 1.

Signs and symptoms of non-CF bronchiectasis

Chronic cough, sputum production and breathlessness are the most commonly described symptoms. Other frequently reported symptoms include recurrent chest infections, fatigue, haemoptysis, chest pain, wheeze and indigestion.1

Comorbidities associated with non-CF bronchiectasis

The most common comorbidities associated with non-CF bronchiectasis are obstructive pulmonary disease; cardiovascular disease; pulmonary hypertension; gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; cognitive impairment; psychological illness; and lung, oesophageal and haematological malignancies.3,5

Investigations

Several initial investigations should be considered in a primary care environment when non-CF bronchiectasis has been identified clinico-radiologically and as part of the initial assessment before or while awaiting specialist review.

Baseline blood tests

The minimum recommended screening for a new diagnosis of non-CF bronchiectasis includes a full blood count, measurement of immunoglobulin (Ig) levels (IgM, IgA, IgG), Aspergillus serology and Aspergillus-specific IgE testing.1 These tests should be conducted before or while the patient is awaiting review to guide the assessment of potential causes. Further testing that a specialist may consider based on the patient’s clinical history and examination findings include:

- autoimmune serology (including antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigen, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody)

- measurement of alpha-1-antitrypsin levels (if airflow obstruction or emphysema is present)

- measurement of vitamin D levels (which correlate with disease severity)

- HIV testing

- human T-lymphotropic virus-1 testing.2

Sweat testing can be considered in young patients with upper lobe-predominant bronchiectasis and other clinical features suggestive of cystic fibrosis.

Sputum samples

For patients who can expectorate, samples should be sent for microscopy, culture and sensitivity. Further investigation includes fungal culture or mycobacterial species culture testing. If nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, such as Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex or Mycobacterium abscessus complex, is suspected, a minimum of three sputum samples should be collected for mycobacterial culture. Repeat sputum culture where appropriate is recommended annually for the screening of colonising organisms.

Lung function testing

Obstruction is the most common pattern observed on lung function testing, occurring in over 50% of patients with bronchiectasis. Other patterns observed include restriction, mixed obstruction and restriction or normal lung function.1 Observing the pattern can help guide whether bronchodilators may be of utility or if coexistent asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are present. Lung function testing should be considered as a baseline test but should not be routinely repeated outside a specialist setting.

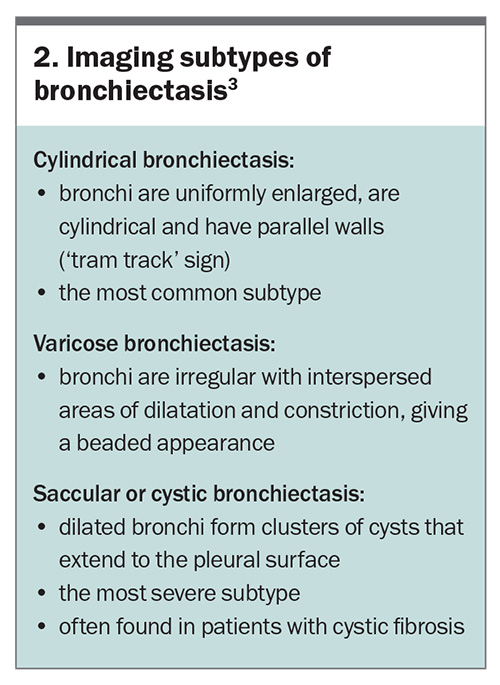

Imaging

In patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of bronchiectasis, high-resolution CT of the chest is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and to assess the severity and extent of disease.2 Specific subtypes of bronchiectasis are delineable on imaging and are summarised in Box 2.3

Other specialised testing

Following respiratory specialist review, more specialised tests may be considered. Bronchoscopy may be used to obtain sputum samples if the patient cannot expectorate and there is concern for opportunistic infections. It also allows for the assessment of the presence of foreign bodies or other causes of endobronchial obstruction and bronchocele formation, such as malignancies. Further assessments for rarer causes may include fractional exhaled nasal nitric oxide testing, nasal ciliary brushings, chloride sweat test, genetic testing for primary ciliary dyskinesia and cystic fibrosis screening.2

Management

The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and European Respiratory Society describe four overarching principles of bronchiectasis management.1,2 These are as follows:

- preserve lung function and halt disease progression

- optimise wellbeing and quality of life for the patient and family

- minimise the frequency and severity of respiratory exacerbations

- reduce symptoms and prevent complications.

Comorbidities that are commonly associated with non-CF bronchiectasis include COPD, asthma, atopy, rhinosinusitis, cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression and low body mass index. Identification of these comorbidities allows for targeted treatment optimisation at the individual patient level. Assessment may involve the assistance of a physiotherapist trained in airway clearance techniques, dietitian, psychologist, immunologist and other subspecialist allied health team members. Ensure vaccinations are up to date according to the National Immunisation Schedules. This includes influenza, pneumococcal (at all ages) and COVID-19 vaccinations and may soon include RSV vaccination if listed for public funding.

Airway clearance and physiotherapy

More than 70% of patients with non-CF bronchiectasis produce sputum daily in varying quantities, colours and consistencies. Airway clearance techniques assist in preventing mucus stasis, mucus plugging and airflow obstruction. Biannual review by a physiotherapist trained in airway clearance techniques is recommended to provide education and ensure an adequate technique is implemented.1,2

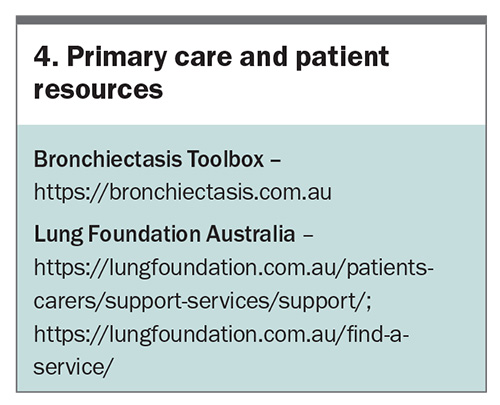

Airway clearance remains a mainstay of daily non-CF bronchiectasis care to reduce exacerbation frequency and prevent or slow irreversible lung destruction. A handy tool in primary care is the Bronchiectasis Toolbox (bronchiectasis.com.au), which includes video guidance on airway clearance techniques. Education from a physiotherapist who specialises in airway clearance to guide training and rehabilitation is ideal, but self-education via the Bronchiectasis Toolbox is also beneficial.

Regular physical exercise is known to be beneficial for several underlying airway diseases. Exercise can improve exercise tolerance, reduce breathlessness and improve quality of life in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis. The recommended duration of moderate-intensity exercise is a minimum of 30 minutes, three times per week. Access to community services may be available via the Lung Foundation Australia (lungfoundation.com.au/find-a-service/).

Hypertonic saline nebulisers may be used on an individual basis in patients with continuing frequent exacerbations; however, they are not currently recommended routinely and are of limited benefit in non-CF bronchiectasis compared with cystic fibrosis.2

Antimicrobial therapy

The use of antimicrobials is challenging in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis, and a key factor is distinguishing between chronic sputum production and acute exacerbation. This is key to both realistic expectations for patient disease management and prevention of emerging antimicrobial resistance.

Due to the nature of non-CF bronchiectasis, patients are exposed to recurrent courses of antibiotics over their lifetime. To minimise the development of antibiotic resistance, the choice of antibiotic should be guided by the micro-organisms cultured and their sensitivities, if known. Awareness of the patient’s baseline microbiome when well by obtaining a sputum culture can help guide antibiotic selection when unwell.

If Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation is not found, empirical treatment with amoxicillin plus clavulanate is often a reasonable first choice. If P. aeruginosa colonisation is found, ciprofloxacin is the required oral antimicrobial, presuming no other organisms are isolated. When oral antibiotics are sufficient to manage an exacerbation, a prolonged course of 14 days should be prescribed.1 Patients not clinically responding as expected should undergo repeat sputum culture testing to ensure no other causative agent is present and hospitalisation for intravenous antimicrobials should be considered. If there is a clear clinical improvement, and an oral antibiotic stepdown alternative is available, therapy can be de-escalated. A total of at least 14 days of treatment should be completed.1,2

Prophylaxis

In patients who have frequent exacerbations (at least three exacerbations requiring antibiotics in the last year), long-term macrolide therapy may be considered following specialist review.1 It is important to exclude underlying nontuberculous mycobacterial infection prior to commencement. Doxycycline is an alternative for patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial infection.

Nebulised antimicrobial prophylaxis may be considered for patients with non-CF bronchiectasis when P. aeruginosa colonisation and frequent exacerbations (at least three per year) are present, or in those who are unable to tolerate or are nonresponsive to long-term oral macrolide therapy following specialist review.2

When P. aeruginosa colonisation is first identified in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis, eradication therapy should be considered.2 Most data supporting this are based on the paediatric and cystic fibrosis population, although consideration may be given to eradication therapy in adults following specialist review.

Oral or inhaled corticosteroids should not routinely be prescribed unless there is a formal diagnosis of asthma or eosinophilic airway disease. Corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis with a blood eosinophil level greater than 3%.1,2,6

Management of acute exacerbations

Exacerbations of non-CF bronchiectasis are defined as at least four of the following:

- change in sputum characteristics

- increase in dyspnoea

- increased cough

- fever higher than 38°C

- increased wheeze

- decreased exercise capacity

- decreased forced expiratory volume in one second

- new radiological or examination findings.

Confirmation of a true exacerbation, rather than simply chronic sputum production, is key to avoiding unnecessary antimicrobial exposure.

Exacerbation management and prevention are key goals of non-CF bronchiectasis management. Exacerbations lead to increased inflammation and progressive lung damage.1 Signs and symptoms suggestive of an exacerbation include changes in sputum quantity, colour or consistency.

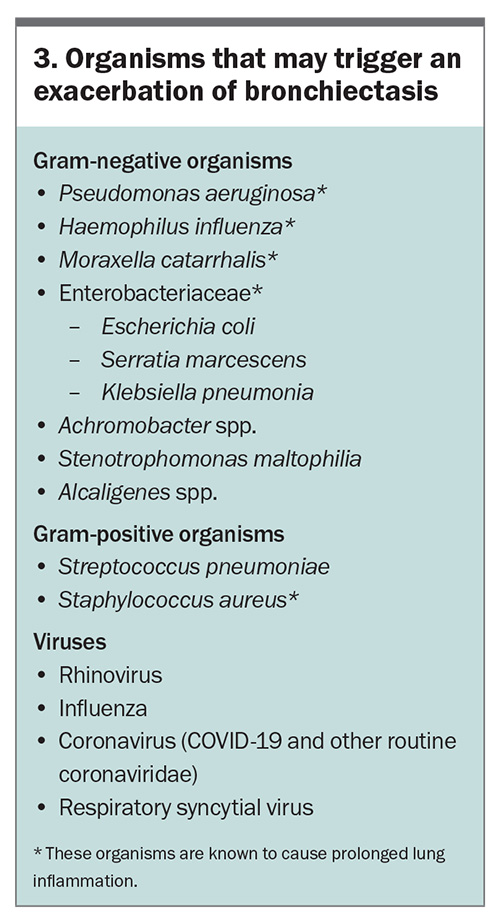

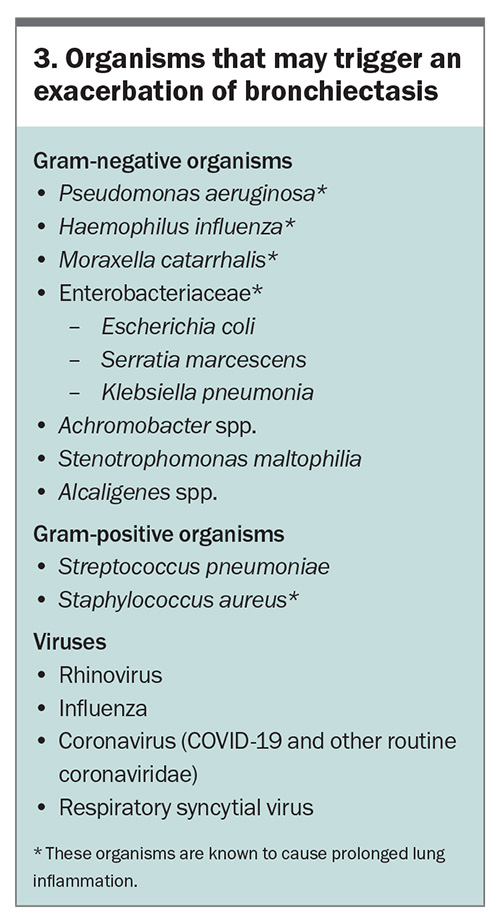

At the first sign of an exacerbation, a sputum sample should be obtained to assist with identification of the causative organism. In the absence of known P. aeruginosa colonisation, first-line treatment should include broad coverage of the common respiratory flora, such as amoxicillin or amoxicillin plus clavulanate for 14 days (given the increasing frequency of amoxicillin-resistant oral flora, such as Haemophilus influenzae). If colonisation with resistant gram-negative bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa, is confirmed, consider ciprofloxacin. Organisms that can lead to an exacerbation of non-CF bronchiectasis are listed in Box 3.

Although fungal organisms (Aspergillus spp., Scedosporium) and nontuberculous mycobacteria (M. avium-intracellulare complex, M. abscessus complex) are associated with progressive non-CF bronchiectasis and may predispose a patient to exacerbations, they are rarely the causative agent, and empirical treatment for exacerbations should not include these agents.

Prognosis and natural progression of bronchiectasis

The rate at which lung function declines is influenced primarily by the number and severity of exacerbations and infections, as well as by the particular organisms colonising the airways.3

Breathlessness is one of the strongest predictors of mortality.1 The organisms associated with prolonged inflammation (as listed in Box 3), if persistently isolated, increase the risk of exacerbations, and lead to poor quality of life and increased mortality.1P. aeruginosa colonisation is associated with more extensive disease, higher degrees of airway obstruction and an increased rate of patient decline. Certain ethnic groups, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Māori and Pacific Islanders, are at higher risk of poor disease outcomes and increased severity of disease.2

The severity of non-CF bronchiectasis can be assessed using the Bronchiectasis Severity Index.7 It utilises clinical, radiological and microbial elements to predict one- and four-year morbidity and mortality, and is also useful in predicting hospitalisation rates.7 Alternatively, the Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index can be used to determine the risk of severe exacerbations requiring hospitalisation and overall mortality, based on an individual’s underlying risk factors.5 Individuals are deemed as low, intermediate or high risk of five-year mortality and risk of hospitalisation for severe exacerbations.3

Specialist input: when is it needed?

A patient with non-CF bronchiectasis should be referred to a respiratory specialist when any of the following features are present:

- radiologically extensive findings

- (i.e. multilobar or saccular type)

- frequent exacerbations (at least three per year)

- haemoptysis

- significant comorbidities that may contribute to bronchiectasis, including underlying autoimmune conditions and corticosteroid or immunosuppressant use

- P. aeruginosa colonisation or nontuberculous mycobacteria observed on sputum microscopy

- moderate-to-severe disability caused by bronchiectasis, as assessed using the Bronchiectasis Severity Index.

Conclusion

Non-CF bronchiectasis is a chronic lung condition involving abnormal, irreversible dilatation of the bronchi where the elastic and muscular tissue is destroyed by acute or chronic inflammation and infection. The condition is caused by episodes of infection, leading to chronic inflammation, which in turn makes the airways more prone to recurrent infection and further inflammatory damage. Patients most commonly present with a chronic productive cough, breathlessness, sputum production and recurrent exacerbations. Appropriate investigations include blood tests, sputum samples and high-resolution CT. Management consists of nonpharmacological and pharmacological measures that aim to preserve lung function, optimise wellbeing, minimise exacerbations and reduce symptoms. Patients with more severe disease often require shared care between the primary care physician and a respiratory specialist. When patients are under GP primary care alone, consider annual clinical review to ensure they are up to date with vaccinations, and assess symptoms and the frequency of exacerbations to determine the need for re-referral to specialist care versus ongoing GP primary care management. Further resources are listed in Box 4. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Ozarczuk: None.

Dr Whitmore has received consulting fees, been a member of the expert working group and received travel fees to attend expert working group meetings from Australian Therapeutic Guidelines.

References

1. Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1-23.

2. Chang AB, Bell SC, Byrnes CA, et al. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) position statement on chronic suppuratives lung disease and bronchiectasis in children, adolescents and adults in Australia and New Zealand. Respirology 2023; 28: 339-349.

3. Nicolson CH, Holland AE, Lee AL. The Bronchiectasis Toolbox - a comprehensive website for the management of people with bronchiectasis. Med Sci (Basel) 2017; 5: 13-20.

4. Keir HR, Chalmers JD. Pathophysiology of Bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 42: 499-512.

5. McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, et al. Comorbidities and the risk of mortality in patients with bronchiectasis: an international multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 969-979.

6. Kapur N, Petsky HL, Bell S, Kolbe J, Chang AB. Inhaled corticosteroids for bronchiectasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 5: CD000996.

7. Minov J, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, Vasilevska K, Stoleski S, Mijakoski D. Assessment of the non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis severity: the FACED score vs the Bronchiectasis Severity Index. Open Respir Med J 2015; 9: 46-51.